Today is Labor Day in the U.S. Though many think of it mostly as a last long weekend for recreation and shopping before the symbolic end of summer, the federal holiday, officially established in 1894, celebrates the contributions of labor.

Today is Labor Day in the U.S. Though many think of it mostly as a last long weekend for recreation and shopping before the symbolic end of summer, the federal holiday, officially established in 1894, celebrates the contributions of labor.

Here are some SocImages posts on a range of issues related to workers, from the history of the labor movement, to current workplace conditions, to the impacts of the changing economy on workers’ pay:

The Social Construction of Work

- The surprisingly racist reason we don’t tip flight attendants

- Luxury and the consumption of labor

- The unsung heroes of the crash landing in San Francisco (pictured)

- Why do firefighters take such risky jobs?

- McDonald’s delusional blame-the-victim budget

- Devaluing hospitality workers

- Domestic behavior as both gendered and raced: Who does what for airlines?

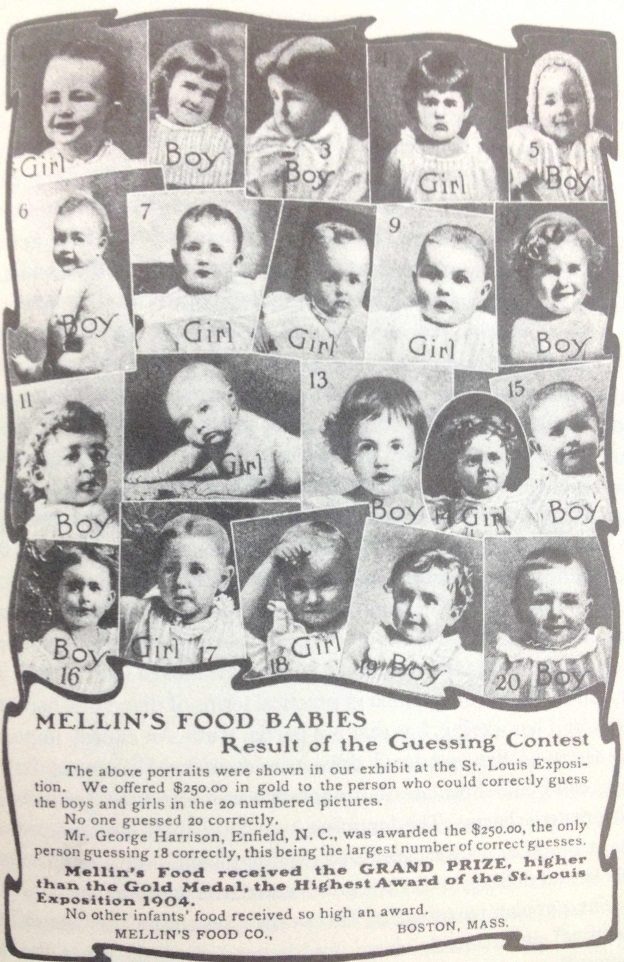

- Child labor and the social construction of childhood

- Child labor, 1908-1912

- Women are 49% of the workforce, but we still think work is for men

Work in Popular Culture

- Children’s books and segregation in the workplace

- Alienation and orange juice: The invisibility of labor

- Hurricane Sandy and high fashion: Portraying a class hierarchy

- Whimsical branding obscures Apple’s troubled supply chain

- The “working family” discourse and the invisibility of individuals

- The DJ in American culture: Resonant but misunderstood

- Whiteness and tokenism on the runway

- The solution to patriarchy? Pantene says shine!

- Forbes’ photostock faux paus (what do women workers look like?)

Unemployment, Underemployment, and the “Class War”

- The “Precariat”: The new working class

- When classes collide: Workers and guests at high end hotels

- Who benefits from government programs?

- $22.62/hr: The minimum wage if it had risen like the incomes of the 1%

- Why can’t conservatives see the benefits of affordable child care?

- Food stamps, public policy, and the working poor

- The striking rise in “missing workers”

- Can the minimum wage cover average housing costs?

- Discrimination against the long-term unemployed

- Jon Stewart on class warfare

- Mike Rowe defends blue-collar manual labor

Unions and Unionization

- What have unions ever done for us?

- Footage of strikes and protests

- “Is your washroom breeding Bolsheviks?”

- A way for feminism to overcome its “class problem”

- Target’s anti-union video for new employees

- Unemployment and support for unions

- César Chávez and the fight for farmworkers’ rights

- Hiring non-union workers to staff picket lines

- “A woman’s place is in her union!”

Economic Change, Globalization, and the Great Recession

- U.S jobs are back, but they’re no match for population growth

- The U.S. is replacing good jobs with bad ones

- Whose economic recovery is it?

- Prison labor and taxpayer dollars

- The austerity agenda and public employment

- Comparing black and white job loss in the recession

- The exploitation of worker productivity

- What kinds of jobs are we gaining in the slow recovery?

- Historical look at changes in types of work

- Two American families trapped in a changing economy

- Race and the economic downturn

Work and race, ethnicity, religion, and immigration

- Distrust for Black entrepreneurs

- Race in the NFL draft

- Are Mexicans the most successful immigrant group?

- Race, criminal background, and employment

- The curious evolution of the sign spinnner

- Linguistic occupational segregation

- International politics and the first African American flight attendants

- Anti-Muslim bias on the French job market

- Race/ethnicity and the pay gap

- Race, ethnicity, and McDonald’s marketing strategy

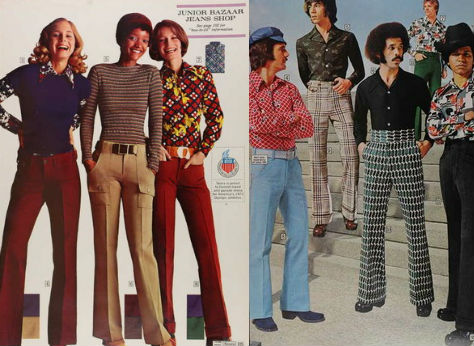

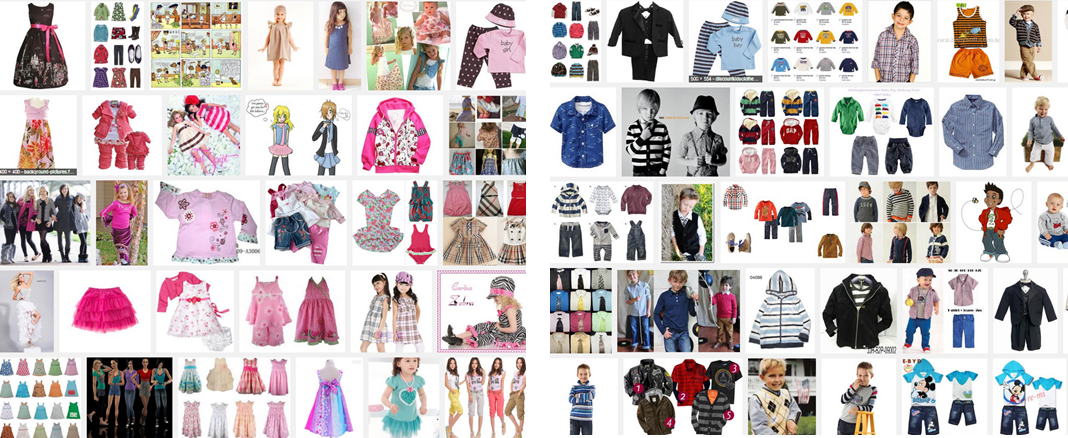

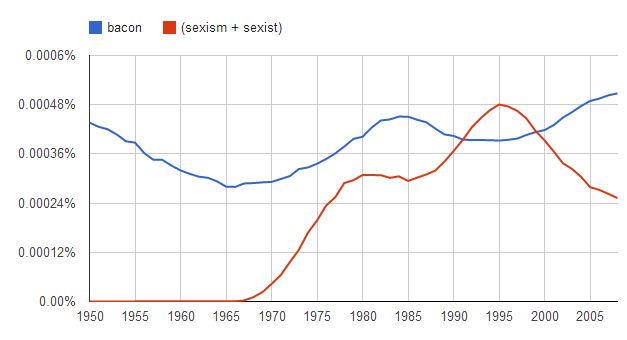

Gender and Work

- Majority of “stay-at-home dads” aren’t there to care for family

- Most women would rather divorce than be a housewife

- Before the stewardess, the “steward”: When flight attendants were men

- Star Trek is scaring the ladies: Why women don’t major in computer science

- What do little girls really learn from “Career Barbies”?

- “Dude, you need to get into nursing”: How organizations recruit men into nursing

- Stay-at-home mothers on the rise among low-income families

- Gender at The New York Times

- Mother, sex object, worker: The transformation of the female flight attendant

- Female movie stars peak at 34, but men see success till the end

- What kind of work does Women’s History month value?

- Men’s and women’s work: It’s the 1950s at Brinks Home Security

- Women’s refusal to be deferent and the words that describe them

- Why “breadwinner moms” don’t portend a coming matriarchy

- Single mother, meet jobless man

- Gender, work, and family time

- First-time mothers and access to paid work leave

- The role of employer selection in gendered job segregation

The U.S. in International Perspective

- Overwork and its costs

- The U.S. is las in paid vacation and holidays

- International comparison of workplace leave policies

- Vacation in international perspective

Academia

- What do professors do all day?

- Gender and the dual career academic couple

- How many PhDs are professors?

- Professors join the “precariat”

Just for Fun

Who is the highest paid employee of your state?

- Secrets of the Internet Adult Film Database

- Two-thirds of college students think they’re going to change the world

Bonus!

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.