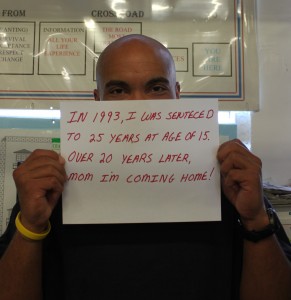

These two. Smart, funny, focused. Both were convicted of committing very serious crimes before they were 16 years old. Both spent time in a youth correctional facility before being transferred to the Department of Corrections where each served more than a decade in a maximum-security prison. Each of them has spent more of his life behind bars than in the community. Yet, their time in prison was not wasted time; they took advantage of opportunities to learn and to grow in positive directions. As I have written before, aging in prison is inevitable, growth is not. These two chose to use the time to cultivate good choices and good habits: they grew and matured. While in prison they became students, citizens, philanthropists, and leaders, volunteering their time and best efforts to help at-risk and troubled youth.

These two. Smart, funny, focused. Both were convicted of committing very serious crimes before they were 16 years old. Both spent time in a youth correctional facility before being transferred to the Department of Corrections where each served more than a decade in a maximum-security prison. Each of them has spent more of his life behind bars than in the community. Yet, their time in prison was not wasted time; they took advantage of opportunities to learn and to grow in positive directions. As I have written before, aging in prison is inevitable, growth is not. These two chose to use the time to cultivate good choices and good habits: they grew and matured. While in prison they became students, citizens, philanthropists, and leaders, volunteering their time and best efforts to help at-risk and troubled youth.

They have worked hard from within prison to try to better their communities, both inside and outside of the prison walls. I’m happy today that both of these men will leave the prison behind them within the next few days and weeks – returning to society as full grown men. They will get another chance at life in the community, carrying within them hard-earned compassion and wisdom. Selfishly, I’ll miss interacting with them on a regular basis. They have been both students and teachers to me, and over the past several years we’ve shared some incredible conversations, projects, and laughs.

Welcome home, guys. One of you will get out in the next couple of days, and the other will follow shortly thereafter. Without internet access, you can’t yet read this post, but I wanted to put it out there anyways. I have no doubt that you will each prove to the world that it is possible to have positive, meaningful, and happy lives after growing up in prison. You’ve earned that chance.

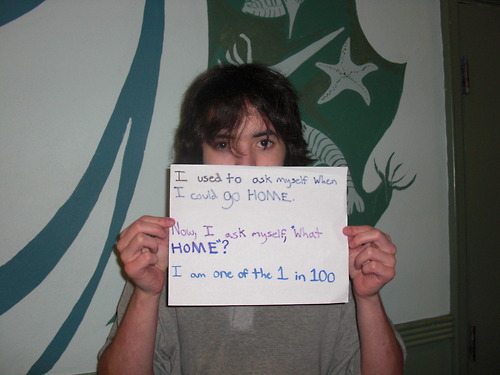

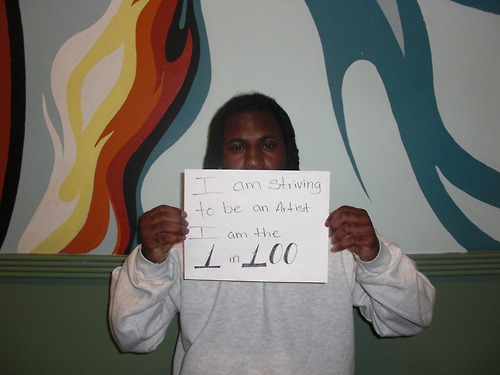

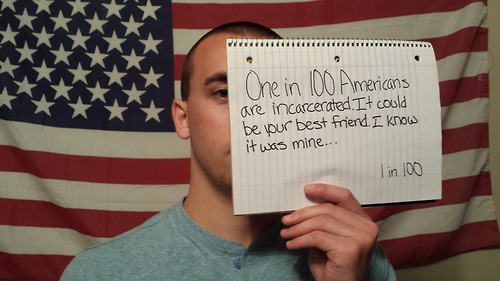

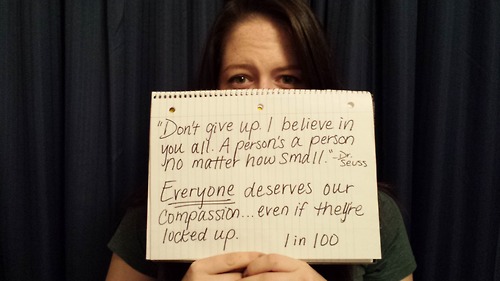

(photos from We are the 1 in 100 site: http://iam1in100.tumblr.com/)

Students from the Inside-Out class also hosted a fundraiser during our Family Field Day, selling lunches of BBQ cheeseburgers, potato or macaroni salad, potato chips, and pink lemonade for $5 per person. The students decided that the funds raised would be equally split between a Hillcrest College Scholarship Fund and a donation to a community group that works with at-risk youth in Portland, Oregon. This fits perfectly with our class discussions on prevention and rehabilitation, and our guests seemed happy to support the cause. I haven’t seen the final numbers yet, but I think the BBQ fundraiser (also held during regular visiting hours on Sunday) raised in the neighborhood of $1000. Amazing.

Students from the Inside-Out class also hosted a fundraiser during our Family Field Day, selling lunches of BBQ cheeseburgers, potato or macaroni salad, potato chips, and pink lemonade for $5 per person. The students decided that the funds raised would be equally split between a Hillcrest College Scholarship Fund and a donation to a community group that works with at-risk youth in Portland, Oregon. This fits perfectly with our class discussions on prevention and rehabilitation, and our guests seemed happy to support the cause. I haven’t seen the final numbers yet, but I think the BBQ fundraiser (also held during regular visiting hours on Sunday) raised in the neighborhood of $1000. Amazing.