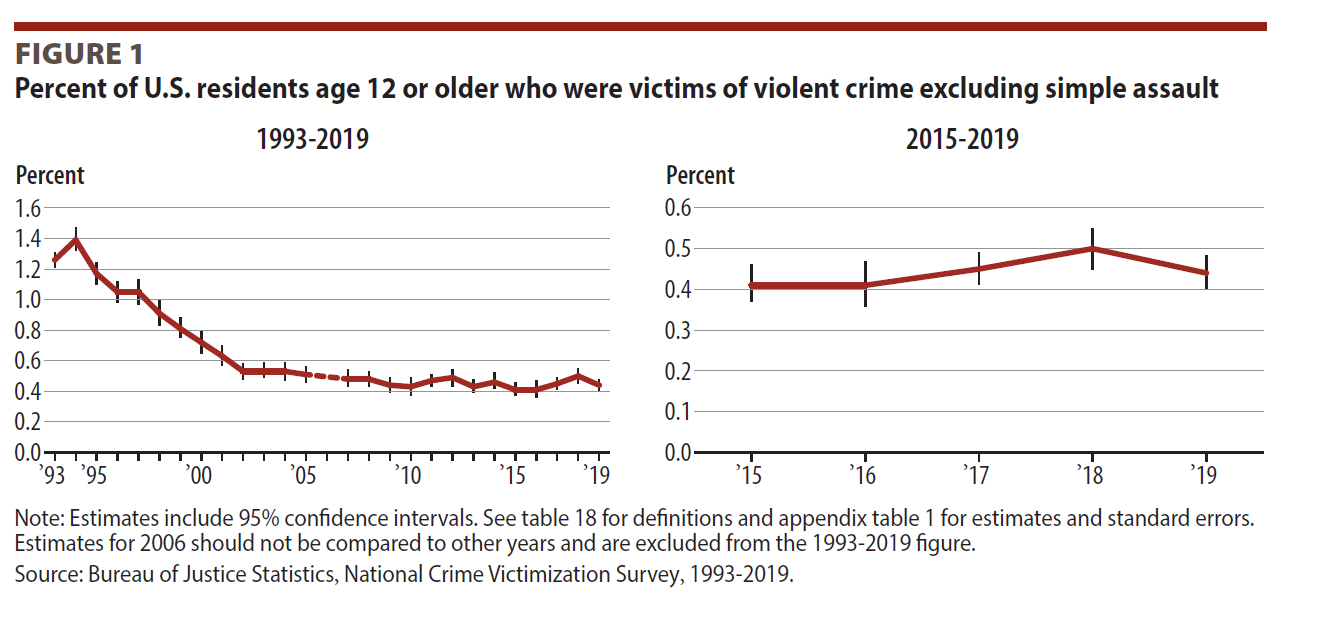

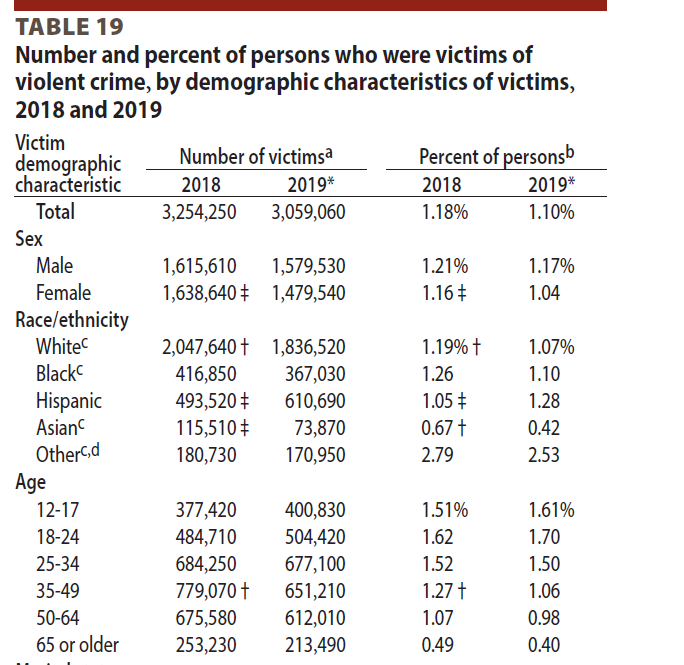

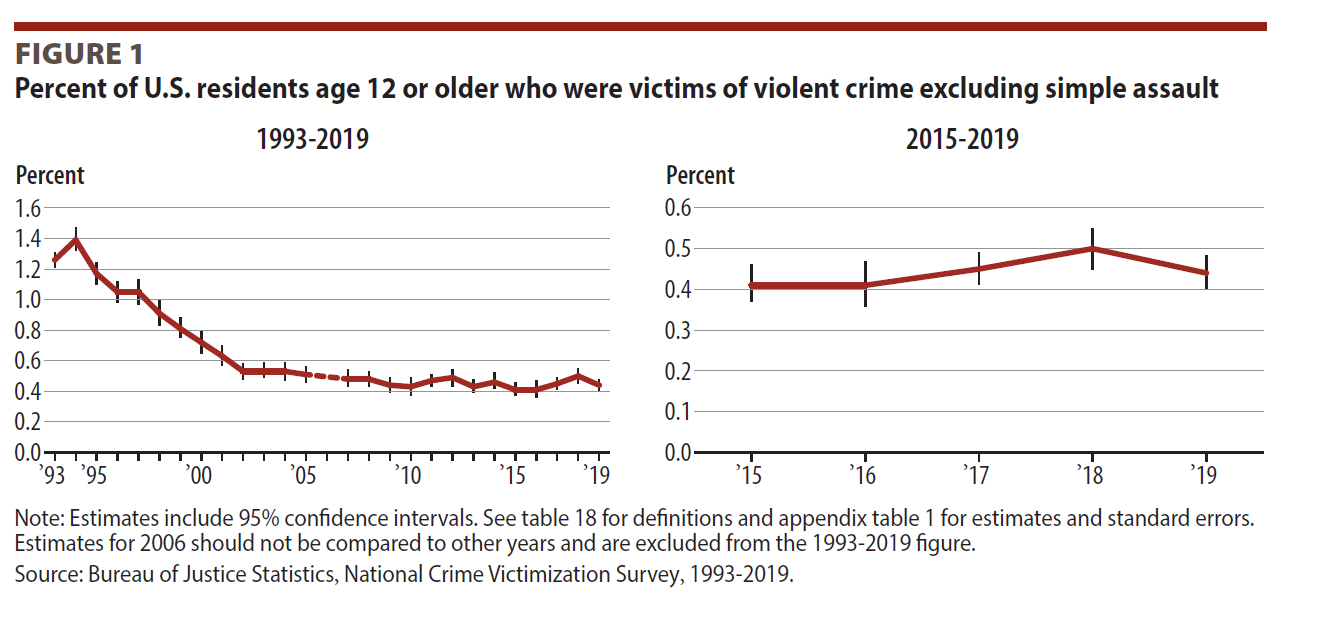

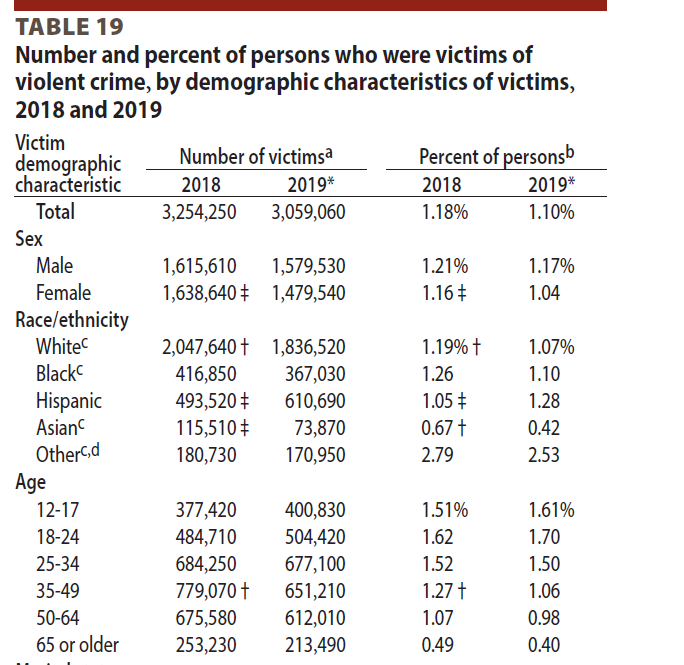

Just released: The 2019 National Crime Victimization Survey shows a small decline since 2018 and continuation of the longer-term crime drop that began in the mid-1990s.

Just released: The 2019 National Crime Victimization Survey shows a small decline since 2018 and continuation of the longer-term crime drop that began in the mid-1990s.

The Oregon State Penitentiary just “celebrated” its 150-year anniversary last week. 150 years is a long time in a west coast state; as a point of comparison, Oregon State University was founded in 1868, so while it is nearing the 150 year mark, the state’s oldest prison has been around longer than its land grant college.

The Oregon State Penitentiary just “celebrated” its 150-year anniversary last week. 150 years is a long time in a west coast state; as a point of comparison, Oregon State University was founded in 1868, so while it is nearing the 150 year mark, the state’s oldest prison has been around longer than its land grant college.

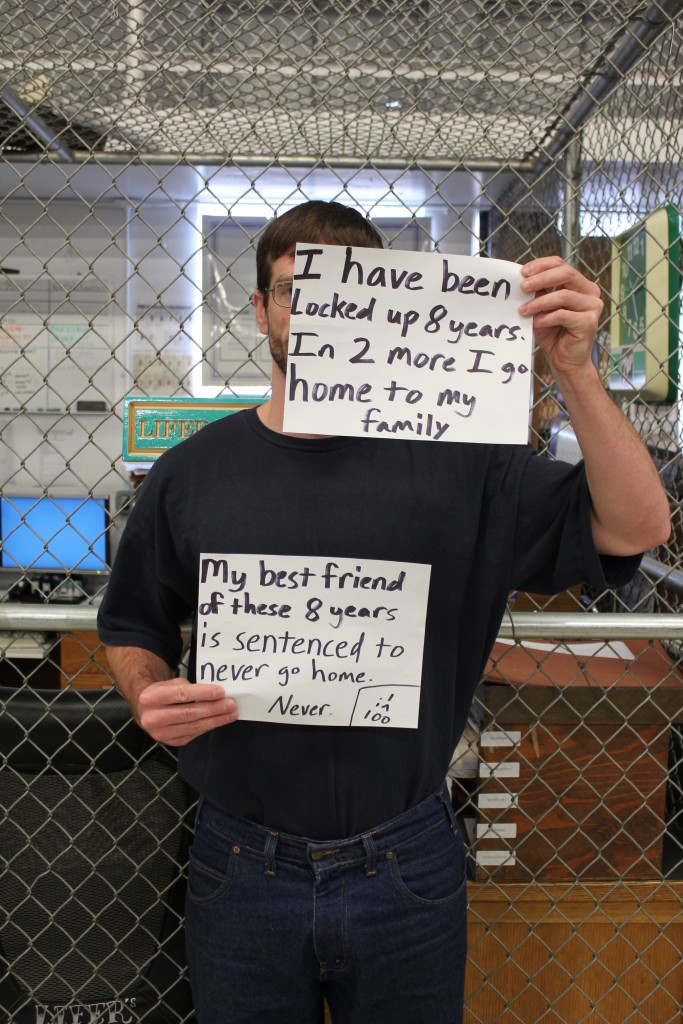

But should we celebrating the longevity of a state prison? As one of my inside friends and collaborators pointed out to officers on the inside: what is there to celebrate? Shouldn’t we instead consider our current prison system a massive failure, given that approximately 1 in 100 people are behind bars and multitudes beyond that are affected by their incarceration? And, if and when they get out, they will face the stigma of a criminal conviction, further limiting their life chances and opportunities for successful reintegration.

To add to the irony of this situation, the men incarcerated in the Oregon State Penitentiary were put on lockdown the day of the celebration so that the dignitaries could honor the anniversary without having to worry about having actual contact with prisoners (or “adults in custody” which is now the preferred label in the state). So, for the prisoners, the “celebration” of this anniversary kept them locked in their cells unable to work at their jobs, unable to go to classes or groups, and unable to go to the yard for exercise and fresh air.

I happen to like OSP a lot as far as prisons go, and I spend a good deal of time there working with the men inside. But, the 150 year mark feels like it should be a time to reflect and think about the future rather than celebrating a century and a half of men locked behind bars.

Now that I am in my 9th year teaching, working with, and befriending men in the Oregon State Penitentiary, I know a fair number of men who have gotten out of prison after serving many, many years. It’s easy, it seems, for the public to believe that men who have served decades in prison simply won’t survive in the outside community; the new technology alone can make it seem a high-speed foreign world. Perhaps we hold too tightly to the image of Brooks, the elderly prisoner from the fictional Shawshank Redemption, as a primary prison reference. Shawshank is a great film, but the men I have known are far more similar to the characters of Andy and Red than Brooks. The fundamental difference is that they have held onto hope. They make plans. They reconnect with family members or create alternative new families. They make lives for themselves on the outside, and they are happy for the chance to do so. They value their opportunities and time on the outside, and they strive to build meaningful new lives.

Now that I am in my 9th year teaching, working with, and befriending men in the Oregon State Penitentiary, I know a fair number of men who have gotten out of prison after serving many, many years. It’s easy, it seems, for the public to believe that men who have served decades in prison simply won’t survive in the outside community; the new technology alone can make it seem a high-speed foreign world. Perhaps we hold too tightly to the image of Brooks, the elderly prisoner from the fictional Shawshank Redemption, as a primary prison reference. Shawshank is a great film, but the men I have known are far more similar to the characters of Andy and Red than Brooks. The fundamental difference is that they have held onto hope. They make plans. They reconnect with family members or create alternative new families. They make lives for themselves on the outside, and they are happy for the chance to do so. They value their opportunities and time on the outside, and they strive to build meaningful new lives.

In studying juvenile delinquency and draconian sentencing, my college students will sometimes wonder what the point is in letting someone out of prison after decades locked up and institutionalized. Is it, indeed, cruel to release such individuals back into the community without full preparation and care, if such preparation is even possible in such a drastic transition? I believe I can answer definitively now: their hope sustains them. I’ve witnessed the joy. I’ve seen men rebuild their lives and celebrate each new day and each opportunity to live in the free world. The chance to rejoin the community is more than worth it to the vast majority of men I have known. Two have stumbled, but the others all push forward. The real cruelty would lie in taking away their hope, in assuming they will fail without letting them truly live their second chances.

I took this photo of the Bridge of Sighs in Venice, the passage between the Doge’s Palace and the centuries-old prison. Legend has it that convicted or condemned men would get one last glimpse of beauty as they crossed from the courtroom to the prison, their last view of freedom steeped in regret and sadness. Today, I like to re-imagine the symbolism. For those men and women released from prison after serving long sentences, we might view them as the gondoliers passing beneath the Bridge of Sighs, a lonely journey with a big reward on the other side: community, sunshine, beauty, and hope.

from The New York Times, article on “Momentum on Criminal Justice Repair“:

[The] bill would sentence most first-time, low-level, nonviolent drug offenders to probation rather than prison; give judges more discretion to grant leniency; create alternatives to prison, like drug-treatment and mental-health programs; reward prison contractors for reducing recidivism; largely end federal prosecution of simple drug possession; and confine mandatory-minimum sentences to high-level traffickers.

In a joint interview last week, I asked Mr. Sensenbrenner about his evolution. And he gave a frighteningly honest response for a man who has sat for decades on the House Judiciary Committee: “We really aren’t exposed to the practical aspect of the criminal-justice system, or what happens or doesn’t happen in the prisons.” So when he and Mr. Scott held hearings on the subject beginning in 2013, Mr. Sensenbrenner said, he got an “education.”

…The legislators’ praise for their own handiwork consisted of repeatedly calling it “evidence-based,” rather than just, right or moral. Which prompted a question: “Isn’t all legislation evidence-based?”

They laughed. Mr. Sensenbrenner said, “No! No! No!” Especially not with criminal-justice bills, Mr. Scott added, recalling the adage “No politician ever votes against a crime bill named after somebody” — meaning a victim. Now America will learn whether a nameless crime bill, defending faceless and unpopular prisoners, is a rare moon with a chance.

This piece was written by Trevor and is posted on our blog for the RISE UP! youth empowerment program at the Oregon State Penitentiary (www.riseuposp.com). The photo is of another prisoner, and is posted on the tumblr site: We Are the 1 in 100.

This piece was written by Trevor and is posted on our blog for the RISE UP! youth empowerment program at the Oregon State Penitentiary (www.riseuposp.com). The photo is of another prisoner, and is posted on the tumblr site: We Are the 1 in 100.

I wake up at 4:55 AM each and every morning. Why? Well, in part, because I can, because I have the freedom to choose at what time I’m going to start my day. This is not true of every day mind you, as many things can change an individual’s schedule or routine. That said, I get up that early, again in part, because when my door most often unlocks, at about 5:15 AM, I don’t want to be in the cell any more where I’ve been for the last number of hours.

I most often choose to eat plain oatmeal with peanut butter, (unless it’s Sunday when the chow hall typically serves eggs, potatoes and toast) because in part I don’t want to experience anymore of the chow hall that I reasonably have to, and because I can afford to eat oatmeal (at $1.00 per pound) and peanut butter (at $2.15 per 16 oz. container) for breakfast.

Work starts at 6:00 AM and I count myself as extremely fortunate to have what we call an industries job. This is an 8-hour a day, 5-days a week, job, in the penitentiary’s industrial laundry. We process linen from the surrounding hospitals, colleges, institutions, etc. Between 1 million and 1 and a half million pounds per month of linen gets processed through our facility. I work in the maintenance department, which is responsible for keeping the equipment running smoothly, maintaining operation of the machinery, scheduling down time for repairs, etc. This job also pays exceedingly well (comparably speaking) as instead of the average monthly income of around $45.00 I earn roughly $150.00 monthly. This has allowed me to maintain regular contact with family through phone calls at 0.16 per minute ($4.80 for a 30-minute phone call) purchase some items to make life more livable through supplementing the food provided from the chow hall with items from canteen / commissary, as well as pay off my restitution and court fees over the last 17-years of roughly $15,000.00 so that should I one day regain an opportunity to live in the community, I’ll be able to start that life without monetary debt.

Typically, around noon I’ll have lunch, which most often gets eaten in that place I’d rather not frequent, the chow hall. Our menu rotates every 3-months (by seasons) with few exceptions, and while that isn’t horrible for a couple of years, when you start passing decades by, it gets redundant and the desire to consume food outside of what gets offered day in and day out grows. I’ve come to think of what I eat as simply fuel.

Between 1 o’clock and 2 o’clock I’m off work and might try to get outside for some sunshine if I’m lucky enough, maybe some exercise, jog around the track or just walk some laps with someone who I need to catch up with for however long. Otherwise it’s reading, studying for work, educational purposes, etc.

Dinner is around 5 PM, that same chow hall that I’d most often rather not go to, however I don’t want to suggest that the food is so bad that we can’t eat it because that’s not the case, many here are well overweight, it’s simply the choices those individuals choose to make in how and what they consume, what level of activity they participate in, whether due to their abilities or basic drive, and what medical conditions may exist in their lives.

During the evening hours I try to write letters, read, call family and friends, maybe attend a function or fundraiser if I’m fortunate enough be involved in something of that nature, educational opportunities, youth outreach programs, etc. For many however, it’s nothing more than watching TV or staring at a blank wall. Again, I’m fortunate, both in my personal agency and my outlook on life.

When I’m asked about “what prison is like” I offer that it is an extremely lonely place, where every moment of every day is dictated for you, and where there’s tremendous opportunities for self-reflection. In the movies, on TV, and through media coverage, you see individuals that get swept up into the justice system and there’s this emphasis on the crime, the trial, entry into prison…then there’s a few scenes of portrayed prison, walking the yard with the tough guys, pumping iron, watching your back in the shower room, etc. and lastly this great experience of being released from prison, back to spending time with family and friends, BBQ’s in the summer-time, and so on and so forth. All very “event orientated” without the day-to-day experiences put on display. In part that’s because you can’t show the day-to-day loneliness, the feelings of exclusion, the feelings of shame and cowardice that accompany an individual’s incarceration. The realization that we’ve not only victimized our actual victims through whatever offense(s) we’ve committed, but we’ve additionally victimized our own families, the community, society as a whole, our friends and loved ones, everyone in fact that we come in contact with. The courts, lawyers, judges, prosecutors, juries, corrections officers, police, detective…and the list goes on and on!

So what do I hope to get across here? For starters, we as prisoners are human beings, individuals who have failed society for whatever reasons and though no excuse relieves us from our poor life decisions, without hope and help to be better people, without redemption, society is all but lost in its entirety through our bad behaviors. In a discussion group with college students not long ago, after describing some of the opportunities available here in the penitentiary in which I reside, one student asked me if we as prisoners deserved such opportunities. I paused before answering that society deserves us to have such opportunities, because if we do not come out of prison with more skills and a more productive mindset then we came in with, we are destined to once again fail society.

This is a day in the life of a prisoner…one who considers himself extremely fortunate in countless ways and for just as many reasons.

With full approval of the administrative team at the Oregon State Penitentiary, I’ve started and will be curating a blog for the RISE UP! youth empowerment program that is largely run by Lifers in the prison. The men of RISE UP! (Reaching Inside to See Everyone’s Unlimited Potential) hope to use the blog to give a unique perspective to youth who may be struggling or who could simply benefit from advice and encouragement from men who may have made bad decisions in their younger days but are now working to better themselves and the community. The men of RISE UP! work with Oregon high schools, including students as well as concerned teachers, parents, and counselors; youth outreach programs; community groups; and religious organizations. Their desire is to end the cycle of incarceration, especially for youth.

With full approval of the administrative team at the Oregon State Penitentiary, I’ve started and will be curating a blog for the RISE UP! youth empowerment program that is largely run by Lifers in the prison. The men of RISE UP! (Reaching Inside to See Everyone’s Unlimited Potential) hope to use the blog to give a unique perspective to youth who may be struggling or who could simply benefit from advice and encouragement from men who may have made bad decisions in their younger days but are now working to better themselves and the community. The men of RISE UP! work with Oregon high schools, including students as well as concerned teachers, parents, and counselors; youth outreach programs; community groups; and religious organizations. Their desire is to end the cycle of incarceration, especially for youth.

I’ll post testimonials and short essays written by the members of RISE UP! to the blog as regularly as possible, and we hope anyone caring for teenagers and young people will find the advice and honesty in their words helpful. Criminologists, you may find their stories, perspective, and advice useful in your own thinking and teaching, as well. The guys want to do everything they can from within the prison to help young people avoid making the kinds of mistakes and decisions that may one day get them in serious trouble. Please share the RISE UP! blog (www.riseuposp.com) with anyone who you think might be interested. If you have questions or comments for the men of RISE UP!, please feel free to put them on the RISE UP! blog. We’ll respond as quickly as possible, but it may take several days as we work through the prison’s channels for communication.

The RISE UP blog is a great, more in-depth companion piece to our We are the 1 in 100 site, which features photos, facts, and brief testimonials from my Inside-Out students (both those inside the prison and the youth correctional facility and the Oregon State University students who shared class with them) over the past several years. Please check out both sites, if you have the time. The men inside have a lot of great positive advice and life lessons to share.

I’ve written quite a bit about my Inside-Out classes and my work teaching and volunteering in prisons and youth correctional facilities on this blog. I’ve shared less about my efforts to connect my on-campus classes to those same facilities and the individuals living within them through service-learning projects, volunteer opportunities, and interactive community impact meetings. These activities affect a much larger number of my university students and can be extremely powerful.

I’ve written quite a bit about my Inside-Out classes and my work teaching and volunteering in prisons and youth correctional facilities on this blog. I’ve shared less about my efforts to connect my on-campus classes to those same facilities and the individuals living within them through service-learning projects, volunteer opportunities, and interactive community impact meetings. These activities affect a much larger number of my university students and can be extremely powerful.

I recently published an article on “‘A Lot of Life Ahead’: Connecting College Students with Youth in Juvenile Justice Settings through Service-Learning,” which is freely available in the Fall 2014 issue of Currents in Teaching and Learning. In the article, I discuss some of the challenges and rewards of trying to organize 45-50 university students to lead interactive sessions with incarcerated youth in a short 10-week quarter and offer advice for other instructors who might be inspired to try it. There’s always quite a bit of chaos involved, but the positive outcomes for all involved make it very worthwhile.

Several of my Oregon State University students are graduating this week, and at least four of them are going into jobs working in state youth correctional facilities. By my count, I’ll have at least eight former students working as staff members in Oregon Youth Authority facilities, with virtually all of them finding this career interest through the direct exposure to the system in my classes. I’m really proud of these students and the fact that I was able to help kindle their passion to work with troubled youth. For me, that’s the real heart of Public Criminology.

My friends and collaborators in the Lifers’ Unlimited Club at the Oregon State Penitentiary are putting together a book of essays, poems, and art by their members and fellow prisoners. They are planning to self-publish the book and sell copies to men inside the prison and their friends/families to raise money for the Angels in the Outfield, a community organization that works with children impacted by crime or child abuse. They gave me the honor of writing the foreword to the book; since the book will likely have a limited, local audience, I am sharing a lengthy excerpt of my piece and my thoughts here:

My friends and collaborators in the Lifers’ Unlimited Club at the Oregon State Penitentiary are putting together a book of essays, poems, and art by their members and fellow prisoners. They are planning to self-publish the book and sell copies to men inside the prison and their friends/families to raise money for the Angels in the Outfield, a community organization that works with children impacted by crime or child abuse. They gave me the honor of writing the foreword to the book; since the book will likely have a limited, local audience, I am sharing a lengthy excerpt of my piece and my thoughts here:

My journey into correctional facilities weaves through universities and has allowed me to spend considerable time in both state youth correctional facilities and state prisons. I consider the Oregon State Penitentiary my home base off of campus, and I feel very fortunate to work closely with the men inside. I began working with men in the Penitentiary in 2006 and started teaching college classes in the facility in January 2007. The men who chose to participate in this new program did so with no promise of incentives, rewards, or college credit. They did it simply for the experience and the novelty of stepping out of their comfort zones to try something different and to potentially bring something of value to others in the prison. The Lifers, particularly, adopted the college program and used their influence to help it gain a foothold and flourish in the institution.

In many ways, I was adopted by the Lifers, as well, and my relationship with the men and the club has only deepened over time. My friends and collaborators in the Lifers’ Club are involved in many of the positive programs, activities, and clubs available in the Penitentiary, and they consistently work to “give back” and to improve the community both inside and outside of the prison walls.

I know that I am one of the lucky ones. I was born a white female at a time when race and gender have a large impact on one’s life chances. I had a supportive family – parents and older siblings who loved me and instilled strong working class values. During the risky teenage years, I was fortunate to be surrounded by protective friends who worked to keep me out of trouble rather than pull me into bad situations. I had teachers who recognized my potential and treated me well. I was encouraged rather than discouraged. Like many others in the outside community, I do not have to face my regrets and shame and sorrow on a daily basis. I am privileged to be able to move on from past mistakes with few if any scars.

Many of the men in the Lifers’ Club did not have these same advantages. Whatever the circumstances that led them to the prison, they are faced with the hard reality that they can’t change their pasts. From this moment forward they can only work toward better futures. Many of the Lifers spend years diligently trying to make amends for their actions in an attempt to restore the debts they may owe and to add value to the world around them.

I bring my university students into the Penitentiary to meet with the Lifers as often as I am allowed to do so. Meeting these men and speaking with them even for a few minutes often changes the students’ perspectives on prisoners and possibility. Even in very brief interactions, they come to see Lifers as three-dimensional human beings with strengths and flaws, regrets and passion. They learn that Lifers are sons, fathers, brothers, and friends, and they are valuable community members looking for ways to contribute to the larger society.

…I believe that on a personal level, change is inevitable. Changing into who you want to be takes work, focus, and commitment. Education is one powerful tool to open doors and help individuals move forward in the directions of their dreams, but there is no replacement for effort, grit, and a little humility. The men in the Lifers Club work tirelessly to improve themselves and to make a positive impact on the community in the ways that they can while limited by their circumstances. They inspire me to do better. For those of us without such limits, what are we doing to make the world a better place? What more can we do?

I am deeply grateful for all that the men in the Oregon State Penitentiary have taught me over the years. And because I believe that “the more you know, the more you owe,” I’ll continue working to share what I have learned.

“Are you for or against?” the correctional officer asked me at the gate.

“Against,” I responded. I had driven nearly two hours through the Georgia countryside to attend a vigil at Georgia State Diagnostic and Classification Prison near Jackson, where the state’s male death row inmates are housed. The state planned to execute Warren Lee Hill at 7:00pm that night. The significance was not lost on me as I drove past beautiful, columned antebellum homes along Georgia’s “Antebellum Trail” (a series of towns spared by General Sherman’s torches in 1864), on my way to a vigil protesting the state’s execution of an intellectually disabled black man.

The officer looked at my driver’s license, wrote down my name and my license plate number on a notepad and directed me to turn left into a red clay dirt patch where other cars were parked. The road straight ahead, leading to the prison facility, was dotted with orange road barriers. As I turned off the main road and in to the makeshift parking area, several more officers dressed in full riot gear directed me with flashlights to a parking spot underneath tall pine trees. The officers instructed me to take everything I needed from my car because I would not be allowed back in after the drug-sniffing dogs had been through it.

I’d never attended a death penalty vigil before, much less one held outside the prison where the execution would take place. I’d visited youth and adult prisons many times in my professional life before grad school and while conducting research, so the rigors of security were not new. A few particulars were markedly different, though. I’d never had drug-sniffing dogs run around and through my vehicle before. Fine looking canines that they were, I held my breath as one seemed to linger a while in my front seat. The correctional officers were courteous at every turn, taking a bit of the edge off the feeling of violation inherent in such scrutiny of myself and my belongings. It was clear to me that had done this before; in fact they had just a few weeks prior at Georgia’s first execution in 2015.

Once the dogs were done with my car I was free to join my fellow vigil-holders in our designated corral. And by corral I mean a semi-grassy area roped off with a picnic table holding a cooler of water provided by the prison in the center. I was grateful to see a biffy nearby, just in case the wait was long. There, people were gathered, chatting and waiting with signs bearing slogans such as “Not in my name” and “Yes, there are alternatives to the death penalty.” A correctional officer stood at the entrance to the corral to monitor our comings and goings. There was a second corral available nearby for anyone “for” the execution. No one stood there that night, though I was told that the previous execution had a solid showing of police officers; the executed man – Andrew Brannan, a Vietnam veteran who claimed to suffer from PTSD – was convicted of killing a sheriff’s deputy in 1998.

We were far enough away from the prison itself that I was unable to see the building through the trees. Our only clue as to what was happening inside the facility would (eventually) come from vans driving down the road carrying witnesses and family members from the execution (to be followed later by the coroner’s van).

Soon after I arrived, we were briefly ushered out of the corral to stand for pictures for the media. A few of my fellow protesters stayed to give comments. Clearly not the occasion for a smile, I stood awkwardly, at the back of the group, channeling as best I could my stoic ancestors’ smile-free family photos (fortunately, the photo featured here excludes me).

As 7:00pm arrived, the vigil organizers – many were affiliated with Episcopal or Catholic churches (clerical collars were in abundance) – invited us all to join in a time of prayer and reading the names of those previously put to death. A representative from Georgians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty informed us that the Supreme Court had just declined to intervene on Lee’s behalf, leaving no further obstacles to the execution.

We stood in a circle, at points holding hands. Prayers were said – including the Lord’s Prayer. Although familiar from my Lutheran upbringing, saying the words in this particular context carried a different meaning (e.g. “forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us”). I managed to choke out most of the words to “Amazing Grace,” our voices echoing off the pine trees surrounding our circle, the death house obscured from view but very present in mind.

As the group took turns reading the names of the people Georgia has executed since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976, I read names and dates of death for numbers 40-42:

John Washington Hightower: June 26, 2007

William Earl Lynd: May 6, 2008

Curtis Osborne: June 4, 2008

After the formal vigil concluded, we stood in our corral, waiting. Although I had dressed relatively well for the chilly 30-degree January Georgia night, I stamped my feet periodically to keep the feeling in my toes.

At about 8:10pm, we spotted headlights from several white vans making their way down the road from the prison. Warren Lee Hill had been dead since 7:55pm.

One of the witnesses to the execution came over to the corral to describe how Mr. Hill had died – no final words, peaceful. A pastor from a local church spoke about his conversations with Mr. Hill, and his belief in Mr. Hill’s reform. A few minutes later, a correctional officer gently informed us it was time to go.

My reasons for attending the vigil were both personal and professional. I’ve never lived in a death penalty state before, so I went in part because I was curious. As a private citizen, I’m opposed to the death penalty on humanitarian and religious grounds. As a criminologist, I know that the practice is an ineffective deterrent to crime, arbitrarily applied, and racially biased (see also this graph); not to mention its financial costs and the inherent risk of putting innocent people to death. I approach the subject in my undergraduate criminology classes knowing that many of my students may be in favor of the death penalty, and I respect their personal opinions. But I never shy away from presenting them with the evidence provided by social science research regarding the death penalty’s lack of deterrent effect and its problematic implementation along racial lines.

As I write this, executions in Georgia are on hold pending an investigation into the drug cocktail the state uses to perform lethal injection. Just a month after Mr. Hill’s death, the state was set to execute its first woman since Lena Baker in 1945. Kelly Gissendaner’s execution was halted at the last minute on March 2nd when the drugs to be injected appeared “cloudy.” An additional execution scheduled for a week later was also postponed. This development obviously calls to mind the botched execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma on April 29, 2014. Ms. Gissendaner has since filed a lawsuit against the Georgia Department of Corrections, citing cruel and unusual punishment brought on by the hours of fear and uncertainly prior to her execution’s postponement, as well as ongoing questions about Georgia’s ability to provide a humane death.

For more on the death penalty in the United States, listen to TSP’s Office Hours podcast with David Garland.

My Inside-Out students and I had the unique opportunity on Monday to welcome one of our inside students to the campus of Oregon State University. E, the young man from the youth correctional facility, has been incarcerated for four years, and it was a very, very big deal for him to be able to come spend the day with us.

My Inside-Out students and I had the unique opportunity on Monday to welcome one of our inside students to the campus of Oregon State University. E, the young man from the youth correctional facility, has been incarcerated for four years, and it was a very, very big deal for him to be able to come spend the day with us.

E is within a year of being released and he hopes to transfer his completed community college credits and attend OSU when he is free to do so. E is on a high honor level at the youth facility, and he is one of the only youths to have permission to occasionally go outside of the fence. Even so, he had to have special permission from two agencies to be allowed to visit OSU and two administrators/staff members from the facility accompanied him.

My wonderful outside OSU students were terrific hosts – meeting E and friends in the morning and giving him an insiders’ tour of the best parts of campus. Because E is a huge sports fan, in this photo we are standing on OSU’s basketball court in Gill Coliseum, and I have other pictures of us standing near home plate on OSU’s baseball field at Goss Stadium. Unfortunately, because of agency rules, I can’t share any of the photos with E in them. I’m in the pink sweater in this photo and E was on my left. To my right are my lovely outside students, Emily, Claire, Jon, and Laura – I am happy to at least share this memory of the day and I was able to give all of the participants a copy of the full photo.

The staff members with E took him to lunch off campus so that he could decompress a bit. I imagine he was completely overwhelmed by being on campus around so many unfamiliar people, sights, and sounds. They came back in the afternoon to meet with a small group of OSU students for an hour, and then E, Laura, Jon, the staff members and I walked around campus giving away free chocolate chip cookies (that had been freshly baked in the youth correctional facility) and flyers with information on incarceration, the youth facility, and how OSU students and faculty might get involved. It was a beautiful, sunny spring-like day, and we all had fun interacting with people on campus and giving out the cookies. I should clarify that I didn’t really help, but I did eat 2 of the cookies, showing an implicit endorsement of the product.

It was a great day. We got to share a part of our lives with E, and I’m sure he went back to the youth facility and shared his experience with the other young men who were not allowed to go on this trip. Perhaps it will make some of these incarcerated youth see that attending OSU or another college/university may be a viable option for them when they get out. The administrators and staff at the youth facility and I hope that this will just be the first of many such visits to campus for youth from the facility over the coming years. I send my OSU students into the facility as often as I can, and it was amazing to have one of our inside guys go the other direction and visit us at Oregon State University. We all have a lot to learn from each other, and – working together – I really believe we can make our corner of the world a better place.