Over on facebook, my friends Raka and Jay asked similar questions about the long-term drop in violence discussed in the previous post.

“They asked, and you answered, about “violence” But what they seem to be thinking about is mass killings by individuals. Are those also on the decline in the US? Who has data on that?”

and

“I’d be interested in knowing the rise and fall rates of different kinds of crimes — one on one homicide versus the movie theater/Sikh temple sort. Michael Hout? Chris Uggen?”

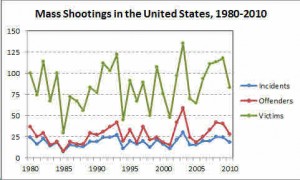

Fortunately, criminologist James Alan Fox has conducted precisely this sort of analysis. His chart below shows the annual number of mass shootings, offenders, and victims in each year from 1980 to 2010.

Professor Fox describes how mass shootings remain quite rare in the U.S. (about 20 incidents and 100 victims per year) relative to other homicides (about 15,000 victims per year), as illustrated in the figure above. Since 1980, I see variation, but no strong upward or downward trend — a non-pattern that we sometimes call “trendless fluctuation,” at least until we can identify its correlates (e.g., a pattern that looks like this).

This is important to bear in mind, as Dr. Fox points out, before (a) we assume there’s been a big increase in mass shootings; and, (b) we attribute this rise to factors that appear to be steadily increasing or declining, such as weapons technology or the availability of mental health care. I’ve no doubt that weapons and mental health care play a big role in such cases, but it is hard to see how either factor could explain the pattern shown above — that is, to predict something that goes up and down with something that just goes up or just goes down over the same period.

The only points I’d add to Professor Fox’s careful analysis is to note that when the numbers are this small the picture could change very quickly. First, it might change if one examined different thresholds or constructed other definitions of mass killings. Second, the chart would look radically different if, heaven forbid, there are more events in the next year or two that push the total number of victims past 150. So, it is probably best to be cautious before making any predictions about the future. All that said, however, it doesn’t appear that we’re currently in the midst of a steep rise in mass killings.

The story was accompanied by the even more compelling Reed Saxon/AP photograph at left, showing faceless inmates in uniform lined up along a wall. Regardless of what I might’ve said about the “typical case,” I suspect that readers will call to mind a picture like this when they think of felon voting. Having edited Contexts magazine and the Society Pages, I know how challenging it can be to illustrate such stories. Even if the typical disenfranchised felon is a fortyish white guy who has served his time, how do you tell his story in a way that will visually engage readers? Show a picture of Uggen watering his lawn? Not likely.

The story was accompanied by the even more compelling Reed Saxon/AP photograph at left, showing faceless inmates in uniform lined up along a wall. Regardless of what I might’ve said about the “typical case,” I suspect that readers will call to mind a picture like this when they think of felon voting. Having edited Contexts magazine and the Society Pages, I know how challenging it can be to illustrate such stories. Even if the typical disenfranchised felon is a fortyish white guy who has served his time, how do you tell his story in a way that will visually engage readers? Show a picture of Uggen watering his lawn? Not likely.