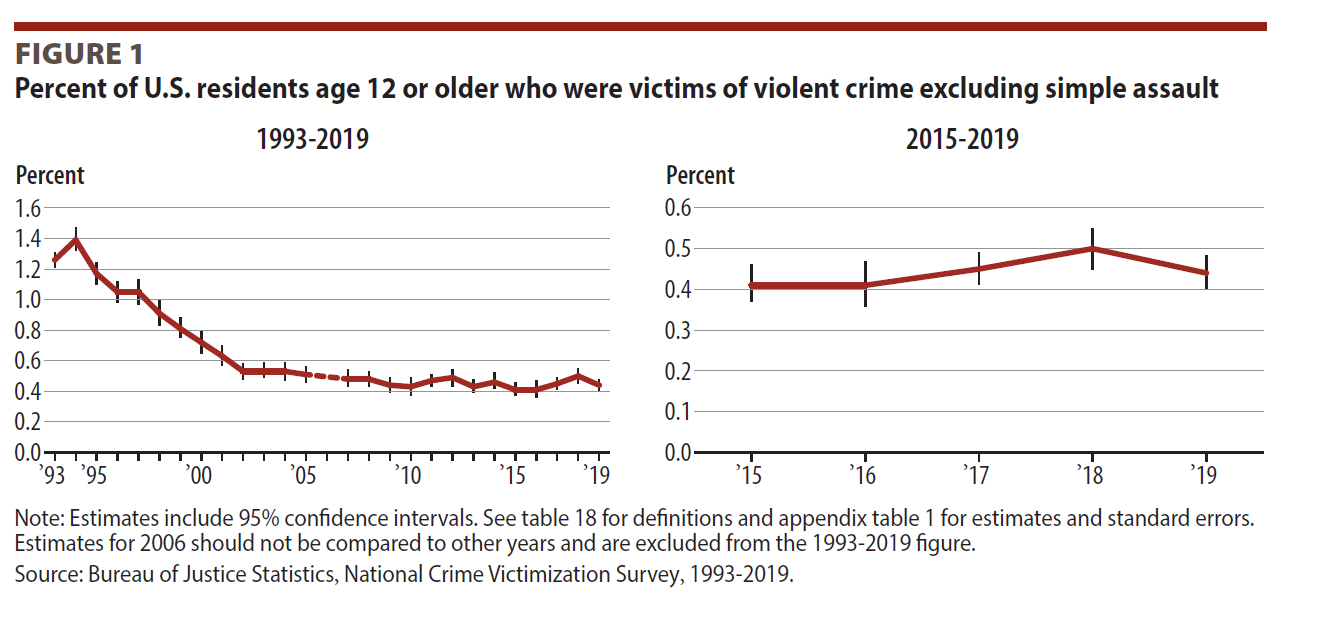

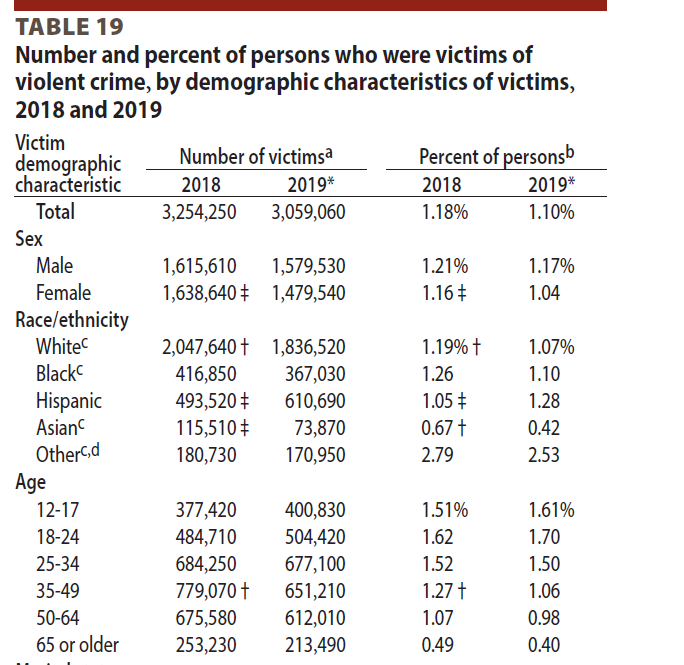

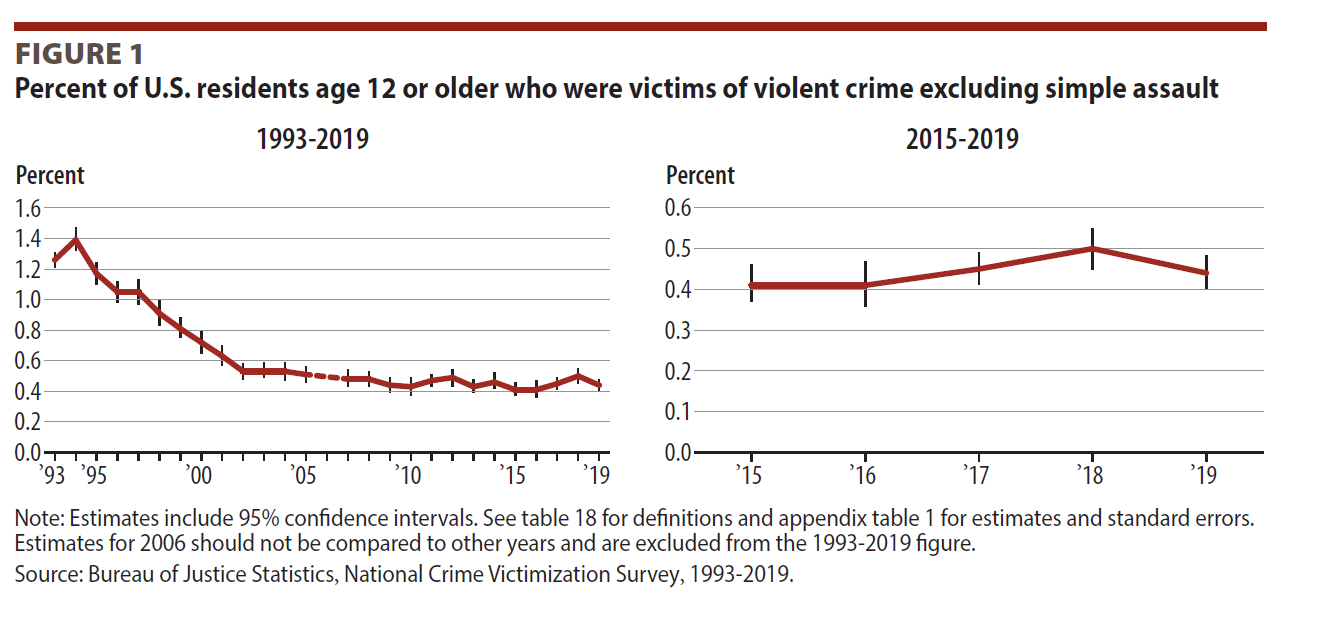

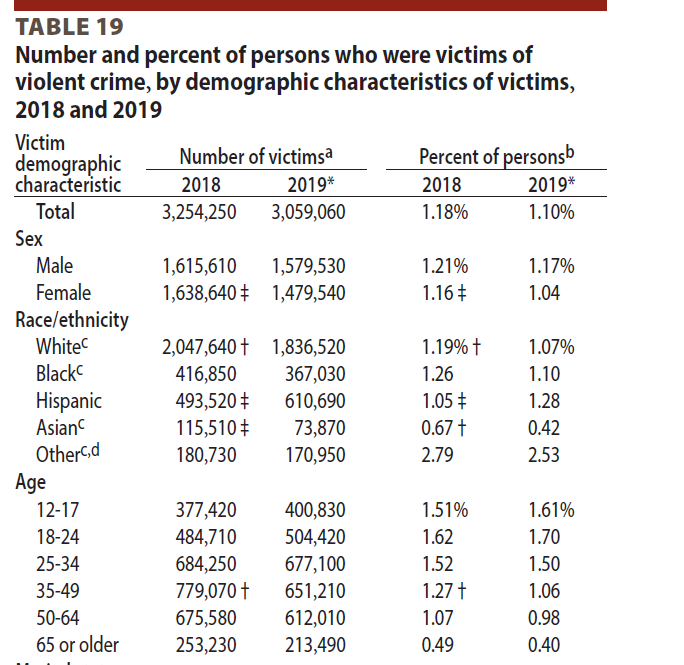

Just released: The 2019 National Crime Victimization Survey shows a small decline since 2018 and continuation of the longer-term crime drop that began in the mid-1990s.

Just released: The 2019 National Crime Victimization Survey shows a small decline since 2018 and continuation of the longer-term crime drop that began in the mid-1990s.

“Are you for or against?” the correctional officer asked me at the gate.

“Against,” I responded. I had driven nearly two hours through the Georgia countryside to attend a vigil at Georgia State Diagnostic and Classification Prison near Jackson, where the state’s male death row inmates are housed. The state planned to execute Warren Lee Hill at 7:00pm that night. The significance was not lost on me as I drove past beautiful, columned antebellum homes along Georgia’s “Antebellum Trail” (a series of towns spared by General Sherman’s torches in 1864), on my way to a vigil protesting the state’s execution of an intellectually disabled black man.

The officer looked at my driver’s license, wrote down my name and my license plate number on a notepad and directed me to turn left into a red clay dirt patch where other cars were parked. The road straight ahead, leading to the prison facility, was dotted with orange road barriers. As I turned off the main road and in to the makeshift parking area, several more officers dressed in full riot gear directed me with flashlights to a parking spot underneath tall pine trees. The officers instructed me to take everything I needed from my car because I would not be allowed back in after the drug-sniffing dogs had been through it.

I’d never attended a death penalty vigil before, much less one held outside the prison where the execution would take place. I’d visited youth and adult prisons many times in my professional life before grad school and while conducting research, so the rigors of security were not new. A few particulars were markedly different, though. I’d never had drug-sniffing dogs run around and through my vehicle before. Fine looking canines that they were, I held my breath as one seemed to linger a while in my front seat. The correctional officers were courteous at every turn, taking a bit of the edge off the feeling of violation inherent in such scrutiny of myself and my belongings. It was clear to me that had done this before; in fact they had just a few weeks prior at Georgia’s first execution in 2015.

Once the dogs were done with my car I was free to join my fellow vigil-holders in our designated corral. And by corral I mean a semi-grassy area roped off with a picnic table holding a cooler of water provided by the prison in the center. I was grateful to see a biffy nearby, just in case the wait was long. There, people were gathered, chatting and waiting with signs bearing slogans such as “Not in my name” and “Yes, there are alternatives to the death penalty.” A correctional officer stood at the entrance to the corral to monitor our comings and goings. There was a second corral available nearby for anyone “for” the execution. No one stood there that night, though I was told that the previous execution had a solid showing of police officers; the executed man – Andrew Brannan, a Vietnam veteran who claimed to suffer from PTSD – was convicted of killing a sheriff’s deputy in 1998.

We were far enough away from the prison itself that I was unable to see the building through the trees. Our only clue as to what was happening inside the facility would (eventually) come from vans driving down the road carrying witnesses and family members from the execution (to be followed later by the coroner’s van).

Soon after I arrived, we were briefly ushered out of the corral to stand for pictures for the media. A few of my fellow protesters stayed to give comments. Clearly not the occasion for a smile, I stood awkwardly, at the back of the group, channeling as best I could my stoic ancestors’ smile-free family photos (fortunately, the photo featured here excludes me).

As 7:00pm arrived, the vigil organizers – many were affiliated with Episcopal or Catholic churches (clerical collars were in abundance) – invited us all to join in a time of prayer and reading the names of those previously put to death. A representative from Georgians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty informed us that the Supreme Court had just declined to intervene on Lee’s behalf, leaving no further obstacles to the execution.

We stood in a circle, at points holding hands. Prayers were said – including the Lord’s Prayer. Although familiar from my Lutheran upbringing, saying the words in this particular context carried a different meaning (e.g. “forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us”). I managed to choke out most of the words to “Amazing Grace,” our voices echoing off the pine trees surrounding our circle, the death house obscured from view but very present in mind.

As the group took turns reading the names of the people Georgia has executed since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976, I read names and dates of death for numbers 40-42:

John Washington Hightower: June 26, 2007

William Earl Lynd: May 6, 2008

Curtis Osborne: June 4, 2008

After the formal vigil concluded, we stood in our corral, waiting. Although I had dressed relatively well for the chilly 30-degree January Georgia night, I stamped my feet periodically to keep the feeling in my toes.

At about 8:10pm, we spotted headlights from several white vans making their way down the road from the prison. Warren Lee Hill had been dead since 7:55pm.

One of the witnesses to the execution came over to the corral to describe how Mr. Hill had died – no final words, peaceful. A pastor from a local church spoke about his conversations with Mr. Hill, and his belief in Mr. Hill’s reform. A few minutes later, a correctional officer gently informed us it was time to go.

My reasons for attending the vigil were both personal and professional. I’ve never lived in a death penalty state before, so I went in part because I was curious. As a private citizen, I’m opposed to the death penalty on humanitarian and religious grounds. As a criminologist, I know that the practice is an ineffective deterrent to crime, arbitrarily applied, and racially biased (see also this graph); not to mention its financial costs and the inherent risk of putting innocent people to death. I approach the subject in my undergraduate criminology classes knowing that many of my students may be in favor of the death penalty, and I respect their personal opinions. But I never shy away from presenting them with the evidence provided by social science research regarding the death penalty’s lack of deterrent effect and its problematic implementation along racial lines.

As I write this, executions in Georgia are on hold pending an investigation into the drug cocktail the state uses to perform lethal injection. Just a month after Mr. Hill’s death, the state was set to execute its first woman since Lena Baker in 1945. Kelly Gissendaner’s execution was halted at the last minute on March 2nd when the drugs to be injected appeared “cloudy.” An additional execution scheduled for a week later was also postponed. This development obviously calls to mind the botched execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma on April 29, 2014. Ms. Gissendaner has since filed a lawsuit against the Georgia Department of Corrections, citing cruel and unusual punishment brought on by the hours of fear and uncertainly prior to her execution’s postponement, as well as ongoing questions about Georgia’s ability to provide a humane death.

For more on the death penalty in the United States, listen to TSP’s Office Hours podcast with David Garland.

When the news came from Ferguson on November 24th, it was hard to know what to do. Each of us possesses some pertinent expertise, whether we study violence, law, race, or criminal justice and injustice. But how and when should we engage? The streets were alive with protesters, police officers, and journalists. The President was calling for calm, which was itself a polarizing message. And Facebook feeds flowed with horrifying videos, rage, and invective, as many were “defriending” and “unfollowing” one another until their social networks were fully purged or converted.

Public scholars can and should step up in such highly-charged political moments, but there was little room to maneuver in those first few days. A dispassionate rendering of cold social facts – on the legal intricacies of grand jury indictment, for example – would ring hollow to those who saw the events in clear moral terms. A straightforward presentation of a pertinent research study – on the effectiveness of police body cameras, for example – would redirect energy and attention away from larger questions. And, to the extent we could actually penetrate the teeming information space, our statements would be reduced to 140-character factoids and channeled to those predisposed to agree with us already. How can we do good public work under such conditions?

In the tense days and nights after the indictment announcements, sociologists such as Michael Eric Dyson and Doug Hartmann made insightful big-picture contributions. Some of us wrote op-eds or gave interviews, others spoke at demonstrations or held teach-ins, and many more revamped our regular teaching and research activities. Like many of you, I found myself in several community forums, most recently with a sitting judge and a television reporter who would moderate our discussion. The talk had been scheduled for months as a wonky “nuts and bolts of justice reform” discussion, but the sudden surge of interest in crime and punishment reshaped our agenda. It would have been foolish, if not impossible, to ignore the protests and issues occurring right outside the door. Interest was high. We moved the event to a larger hall when we reached capacity and we recorded the proceedings for later broadcast. As I looked around the racially and socially diverse crowd of journalists, students, lawyers, teachers, police officers, formerly incarcerated people, and community members, I knew that dozens if not hundreds of my colleagues were similarly engaged in their communities. I claim no special expertise on these topics or events, but I share these personal reflections and suggestions in hopes of encouraging other section members who might wish to engage the public.

Position and Language

When speaking with a public audience, I try to remember that there are other experts in the room. For example, a middle-aged white guy like me has little authority or legitimacy regarding the subjective experience of interacting with police as a young African American in the central city. Put simply, many in attendance did not want or need me to lecture to them about how their communities are policed. So my job was to give due attention to race and justice while also acknowledging the real limits of my perspective and the research evidence I would cite. Thinking a personal story might help, I opened by acknowledging the #BlackLivesMatter and #CrimingWhileWhite campaigns and briefly noting my own juvenile arrests – and how the “judicious and humane discretion” of three Minnesota police officers was so important in my life that I thanked them by name in my dissertation acknowledgements. After repeated exposure to the Michael Brown and Eric Garner videos, few in the audience would have argued that men of color have been getting the same breaks that I received. As importantly, few would have argued against providing the same sort of breaks to all young people. Yet framing the issue in this way also helped make such points without bashing or demonizing those police officers – several of them my former students — who showed up at the forum.

This was not the night for a PowerPoint presentation, as personal stories are often more effective than statistics in helping audiences evaluate and reframe their image of crime and justice. I also called out Emily Baxter’s WeAreAllCriminals.com. Using evocative images and personal accounts, WAAC shows the blurriness of the criminal/non-criminal distinction. Terminology plays a similar role in public scholarship, where the wrong descriptor can quickly alienate half the audience. I try to use simple, neutral language to facilitate discussion, addressing people formally (e.g., as Ms. Johnson or Judge Castro, rather than as Angie or Lenny). In such forums, identifiers such as “police officer” or “formerly incarcerated” are more helpful and precise than terms like “cop” and “offender.”

Content and Context

Academics sometimes try to teach a whole semester’s worth of material in an hour, which dramatically exceeds anyone’s ability to process new information. I try to identify three to five key points and to make sure that they are well-supported in the literature. That is, that they are “near-consensus” areas in our field that the public might not yet appreciate. That night, I called out: (1) Tom Tyler’s work on procedural justice, and how treating people with dignity and respect engenders greater trust and legitimacy, regardless of the outcome of a citizen’s encounter with the criminal justice system; (2) social-psychological research on implicit bias, which shows that the great majority of Americans, including police officers and professors, hold unconscious group-based biases that affect our behavior; (3) a few well-chosen statistics on the basic race-specific rates of arrest and incarceration in our community; and, (4) the proportion of these arrests that are for low-level offenses that rarely result in prosecution or conviction. Local evidence is critical because the audience is far more engaged in practices close to home (and more likely to dismiss or discount bad things that happen elsewhere). Public criminology can also provide an important myth-busting function in such cases. For me, this meant calling out states like Minnesota and Wisconsin for having the nation’s worst racial disparities in correctional populations – a difficult but essential truth for the audience to grasp. Context is also important for drawing local, national, and international comparisons. For example, I explained how my home state was admirably stingy with prison beds, but profligate in putting people on very long probation terms.

Hope and Questions

Public events, to a far greater extent than academic talks, should leave the audience with a sense of efficacy, or at least hope for real change. I made sure to note that after four decades of rising incarceration, that criminal punishment had finally begun a modest decline. And, of course, that our community and the nation had enjoyed a 50 percent crime drop over the past two decades. To put this drop in perspective, I explained how this meant a decline from 100 Minneapolis murders in 1995 to about 40 the past few years. Nationally, I pointed to bipartisan reform efforts such as the REDEEM Act, cosponsored by Senators Corey Booker and Rand Paul. Locally, I identified bipartisan reforms such as the new Minnesota expungement law and a new ban-the-box provision that bars organizations from asking about criminal records on job applications, but permits them to inquire at the interview stage. I also tackled issues in my own area of research expertise, including local challenges to felon disenfranchisement and the broader problem of “piling on” so many collateral sanctions that they become criminogenic. In particular, I described recent testimony on behalf of six “model probationers,” who were hauled into court and charged with new felonies because they had voted while still “on paper.” A broad coalition was assembling to challenge the voting ban (including the district attorney charged who prosecuted those cases) and several audience members approached me after the event to ask how they could get involved. Finally, I spoke about the costs of diminished trust in the criminal justice system, including Todd Clear and Natasha Frost’s argument that the discretion to make back-end sentencing adjustments can help curb excess or gratuitous punishment – even, or especially, for those serving long sentences for violent crimes.

Public events work best when audience members have a chance to engage the speakers, and we received an impressive range of audience questions that evening. When asked about the prospects for a new social movement around criminal justice reform, I could applaud the efforts of students — and the members of this section — to shine a brighter light on crime, law, and justice in the contemporary United States. As a medical school colleague is fond of saying, sunshine can be a marvelous disinfectant. So too can public criminology.

For further reading, see Doug Hartmann’s Ferguson, the Morning After; Insights on Crime and Punishment from a Judge and a Sociologist, and Public Criminologies (with Michelle Inderbitzin).

Reprinted from Crime, Law & Deviance News, FALL/WINTER 2014 -2015

Newsletter for the Crime, Law & Deviance section of the American Sociological Association

The Minneapolis Star-Tribune reports that a group of “sex offenders” are registering to vote and plan to run for elected office. I put “sex offenders” in quotations because these voters and office-seekers are not currently under supervision for any crime. Instead, they are “civilly committed,” which means that they have either already completed their criminal sentences or, as is the case for over 50 clients, they were never charged as an adult for a sex offense. Although they are euphemistically called “clients” rather than prisoners, most will likely be locked away forever.

How can we continue to lock someone up after they have done their time? The state Department of Corrections generally reviews those convicted of sex crimes at the end of their sentences, referring those deemed dangerous to county attorneys, who may then file a petition for commitment with the district courts. Although civil commitment is rare in many places, Minnesota does this a lot — there are currently about 700 such clients in two secure facilities in the state. How many are released? The program has been in operation for over 20 years, but only 2 people have ever been provisionally discharged from the program.

In a federal class action lawsuit, U.S. District Court Judge Donovan Frank has raised serious questions about the program’s constitutionality. To date, however, the residents/inmates have received little hope or relief and the trial has been pushed back until next year. Given the hyper-stigma surrounding sex offending, few brave souls will act or advocate on behalf of the people in the program. So, they are doing their best to advocate for themselves and to work within what is increasingly acknowledged as a broken system — exercising their rights to vote and seek office.

While the article by Chris Serres and Glenn Howatt contains a wealth of information, they omitted one other factoid that speaks to the program’s sustainability: according to the state Department of Human Services, the per diem cost of the program is $341. This is approximately $125,000 per inmate per year, or roughly four times the cost of the $86 per diem at the state’s correctional facilities. As law professor Eric Janus once put it, “The option of doing nothing would not be responsible from either a legal or fiscal perspective.”

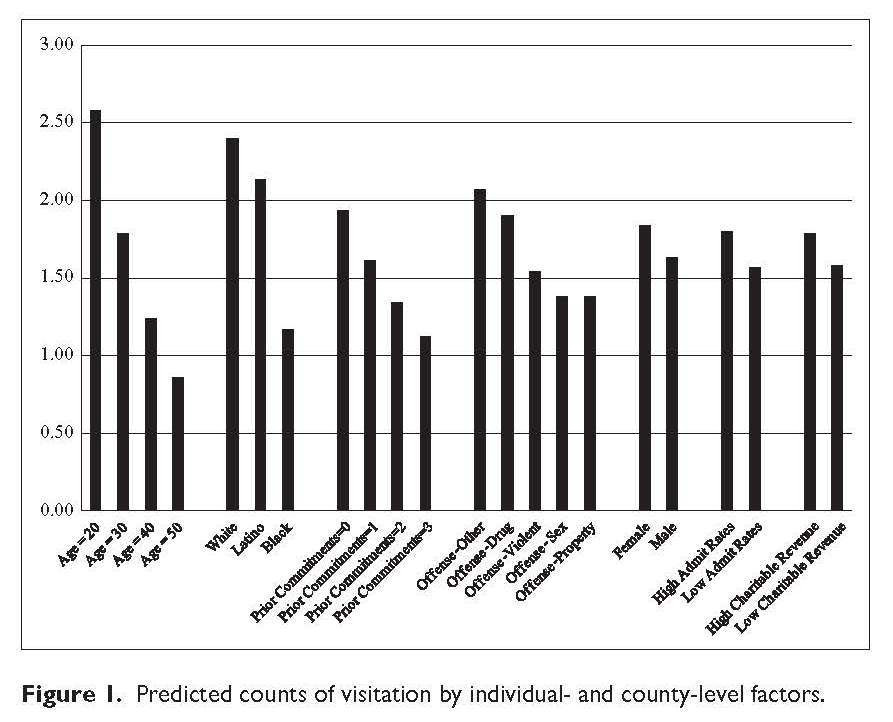

Prisoners who can maintain ties to people on the outside tend to do better — both while they’re incarcerated and after they’re released. A new Crime and Delinquency article by Joshua Cochran, Daniel Mears, and William Bales, however, shows relatively low rates of visitation. The study was based on a cohort of prisoners admitted into and released from Florida prisons from November 2000 to April 2002. On average, inmates only received 2.1 visits over the course of their entire incarceration period. Who got visitors? As the figure below shows, prisoners who are younger, white or Latino, and had been incarcerated less frequently tend to have more visits. Community factors also shaped visitation patterns: prisoners who come from high incarceration areas or communities with greater charitable activity also received more visits.

There are some pretty big barriers to improving visitation rates, including: (1) distance (most inmates are housed more than 100 miles from home); (2) lack of transportation; (3) costs associated with missed work; and, (4) child care. While these are difficult obstacles to overcome, the authors conclude that corrections systems can take steps to reduce these barriers, such as housing inmates closer to their homes, making facilities and visiting hours more child-friendly, and reaching out to prisoners’ families regarding the importance of visitation, both before and during incarceration.

It takes courage to tell a big audience of strangers how your picture somehow ended up next to the headline “Drug Bust Nets Large Haul: Police Find Cocaine, Methamphetamine, and Viagra.” The excellent Life of the Law podcast team brought a series of such painfully honest and powerful stories to the stage this summer. These two are my favorites, from two outstanding young scholars and friends.

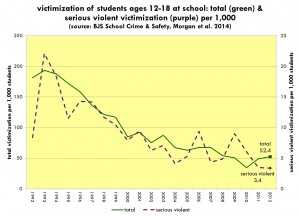

Anyone interested in School Crime and Safety should check the new joint report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics and National Center for Education Statistics. I graphed a few of the statistics below, but there is a great wealth of information on teachers, bullying, weapons, and student perceptions of safety. Although any level of school violence is troubling, the report seems to offer more good news than bad. Total victimization rose from slightly from 2011-2012, but serious violent victimization (rape, sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault) has been flat or declining at about 3.4 victimizations per 1,000 students. Moreover, indicators such as the percentage of students carrying a weapon to school are continuing to decline.

Shock, frustration, and rage. That’s our reaction to the hate-filled video record that Elliot Rodger left behind. The 22-year-old, believed to have killed 6 people in Santa Barbara last night, left behind a terrible internet trail.

Shock, frustration, and rage. That’s our reaction to the hate-filled video record that Elliot Rodger left behind. The 22-year-old, believed to have killed 6 people in Santa Barbara last night, left behind a terrible internet trail.

I cannot and will not speculate about the “mind of the killer” in such cases, but I can offer a little perspective on the nature and social context of these acts. This sometimes entails showing how mass shootings (or school shootings) remain quite rare, or that crime rates have plummeted in the past 20 years. I won’t repeat those reassurances here, but will instead address the bald-faced misogyny and malice of the videos. It outrages us to see a person look into a camera and clearly state his hatred of women — and then, apparently, to make good on his dark promises. It also raises other awful questions. Are these sentiments generally held? If you scratch the surface, are there legions of others who would and could pursue “retribution” as Mr. Rodger did? Is serious violence against women on the rise?

Probably not. Rates of sexual violence in the United States, whether measured by arrest or victimization, have declined by over 50 percent over the last twenty years. As the figure shows, the rape and sexual assault victimization rate dropped from over 4 per 1000 (age 12 and older) in 1993 to about 1.3 per 1000 in 2012. And, if you add up all the intimate partner violence (including all rape, sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault committed by spouses, boyfriends, or girlfriends), the rate has dropped from almost 10 per 1000 in 1994 to 3.2 per 1000 in 2012. The numbers below include male victims, but the story remains quite consistent when the analysis is limited to female victims.

Of course, misogyny and violence against women remain enormous social problems — on our college campuses and in the larger society. Moreover, the data at our disposal are often problematic and the recent trend is far less impressive than the big drop from 1993 to 2000. All that said, “retribution” videos and PUA threads shouldn’t obscure a basic social fact: 22-year-olds today are significantly less violent than 22-year-olds a generation ago.

for more on masculinity and mass violence, see There’s Research on That!

I hope folks are following some of the really powerful crim content on TSP these days. To name just 5…

1. The Cruel Poverty of Monetary Sanctions by Alexes Harris — a terrific piece on prisoners and debt

2. A Crimmigration roundtable, with Tanya Golash-Boza, Ryan King, and Yolanda Vázquez

3. Debt and Darkness in Detroit by David Schalliol, on streetlights and fear of crime in a bankrupt city

4. A new Crime topics page to pull all this work together, edited by Sarah Lageson and Suzy McElrath

5. Crime and the Punished, our new book volume with WW Norton!

In the wake of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s sad death, many are calling for various “harm reduction” approaches to substance use. Proponents of harm reduction have identified lots of ways to reduce the social and personal costs of drugs, but they often require us to shift our focus from the prevention of drug use itself to the prevention of harm. Resistance to such approaches often hinges on the notion that they somehow tolerate, facilitate, or even subsidize risky behavior.

This tension emerged clearly in my new article with Sarah Shannon in Social Problems. We re-analyzed an experimental jobs program that randomly assigned a basic low-wage work opportunity to long-term unemployed people as they left drug treatment. In some ways, the program worked beautifully. The job treatment group had significantly less crime and recidivism, especially for predatory economic crimes like robberies and burglaries. After 18 months, about 13 percent of the control group had been arrested for a new robbery or burglary, relative to only 7 percent of the treatment group. Put differently, 87 percent of those not offered the jobs survived a year and a half without such an arrest, relative to 93 percent of the treatment group who were offered jobs.

A randomized experiment that shows a 46 percent reduction in serious crime is a pretty big deal to criminologists, but the program has still been considered a failure. In part, this is because the “treatment” group who got the jobs relapsed to cocaine and heroin use at about the same rate as the control group. After 18 months, about 66 percent of the control group had not yet relapsed, relative to about 63 percent in the treatment group. So, there’s no evidence the program helped people avoid cocaine and heroin.

From an abstinence-only perspective, such programs look like failures. Nevertheless, even a crummy job and a few dollars clearly helped people avoid recidivism and improved the public safety of their communities. So, did the program work? From a harm reduction perspective, a jobs program for drug users surely “works” if it reduces crime and other harms, even if it doesn’t dent rates of cocaine or heroin use.

Productive Addicts and Harm Reduction: How Work Reduces Crime – But Not Drug Use

Christopher Uggen and Sarah K. S. Shannon

Social Problems

Vol. 61, No. 1 (February 2014) (pp. 105-130)From the Works Progress Administration of the New Deal to the Job Corps of the Great Society era, employment programs have been advanced to fight poverty and social disorder. In today’s context of stubborn unemployment and neoliberal policy change, supported work programs are once more on the policy agenda. This article asks whether work reduces crime and drug use among heavy substance users. And, if so, whether it is the income from the job that makes a difference, or something else. Using the nation’s largest randomized job experiment, we first estimate the treatment effects of a basic work opportunity and then partition these effects into their economic and extra-economic components, using a logit decomposition technique generalized to event history analysis. We then interview young adults leaving drug treatment to learn whether and how they combine work with active substance use, elaborating the experiment’s implications. Although supported employment fails to reduce cocaine or heroin use, we find clear experimental evidence that a basic work opportunity reduces predatory economic crime, consistent with classic criminological theory and contemporary models of harm reduction. The rate of robbery and burglary arrests fell by approximately 46 percent for the work treatment group relative to the control group, with income accounting for a significant share of the effect.