Reading press reports on school bullying got me thinking about the limits of my own expertise and about how social scientists can sometimes contribute to debates even when we are not experts. I always tell graduate students to imagine their expertise as a series of concentric circles radiating outward from the core stuff they know best. They should be grade-A champion world authorities on their dissertation topics, possess solid expertise in their specific areas of research and teaching, and they should know enough about methods and evidence to evaluate claims made by others in the broader fields in which they work. But even when we are not experts, we can always raise questions.

The question I’d raise here is simply whether getting tough on bullying will worsen racial disparities in education. Bullying is a hot issue these days, with a steady drumbeat of legislation and opinion pieces urging us to “strengthen” anti-bullying laws. At the same time, there is deep and abiding concern about closing the gaps in education. Now I can’t claim any real expertise in bullying or in educational attainment, but I can offer a respectful heads-up to policy folks as they craft new anti-bullying laws and practices. How are you thinking about their likely racial impact? I ask because stricter regulation of a broad set of behaviors like bullying could worsen racial disparities in school discipline.

I’ll explain my rationale for this heads-up below, but I really want to make the more general point that sometimes social scientists can contribute to public debates even when we aren’t the leading experts on a topic. We have to be more careful and guarded in our claims, of course, when our expertise is limited to reading and teaching what others have written. Still, we can provide a service even when we raise questions or help people “connect the dots” in a useful way. My approach is usually to just point to the “dots” that I’ve found convincing and to ask questions about whether and how the policy action being considered might take account of them.

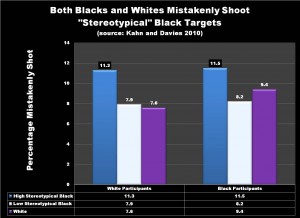

I base my bullying heads-up on two related lines of social science research. The first concerns implicit racial bias in perceptions of threat and dangerousness. The chart below is taken from a 2010 piece by Kimberly Kahn and Paul Davies, who showed that both White and African American study participants were more likely to assume people with stereotypically African American features had guns in a split-second shoot/don’t shoot computer simulation. Both Whites and African Americans mistakenly shot targets with darker skin, broader noses, and fuller lips about 11 percent of the time, relative to 8 or 9 percent of the time for White targets and “low-stereotypical” African American targets. This sort of pattern is evident in a lot of research on “implicit bias,” where whites tend to be perceived as more safe and less threatening than (otherwise identical) African Americans. My sense from this research is that actions by darker-skinned students might be more likely to be perceived and punished as bullying than when the same actions are taken by lighter-skinned students.

The second “dot” is that most of the self-report studies I’ve seen also show racial differences in self-reported bullying behavior. The chart below is taken from a 2007 study in the Journal of Adolescent Health by Aubrey Spriggs and colleagues. According to their analysis of a nationally representative sample of 6th to 10th graders, African American children were significantly less likely than White children to report they were targets of bullying and significantly more likely to report engaging in bullying behaviors themselves.

About 17 percent of African American kids self-reported physical bullying, relative to 15 percent of Hispanic youth, 11 percent of Whites, and 12 percent of those of other groups. The targeting or victimization numbers go in the other direction, with 12 percent of African Americans reporting being physically bullied, relative to 15 percent of whites. The same patterns seem to hold for other types of bullying (verbal, relational, and cyber) as well.

Experts on bullying can surely provide a better account of these figures than I can, but it looks to me as though enforcing vague bullying rules more strictly could worsen racial disparities in school discipline and, perhaps, educational attainment. I don’t know enough about bullying or schools to make strong policy recommendations, but it seems there is enough evidence here to at least put the question of racial impact to those charged with making or enforcing new rules. A small but significant difference in self-reported bullying combined with implicit bias in enforcing bullying rules could lead to pronounced disparities. That doesn’t mean anyone should ignore bullying, of course, it just means that we might consider steps to help reduce or mitigate bias when we change the rules.

One proposed Minnesota bill would define bullying as conduct “so severe, pervasive or objectively offensive that it substantially interferes with the student’s educational opportunities,” or places the student in “actual and reasonable” fear of harm, or substantially disrupts school operations. This seems to set a pretty high bar, which would appear to be racially neutral — unless, of course, students, teachers, and administrators are already more afraid of darker-skinned students. If so, there is some evidence to suggest they will be quicker to pull the trigger in suspending or expelling such students.