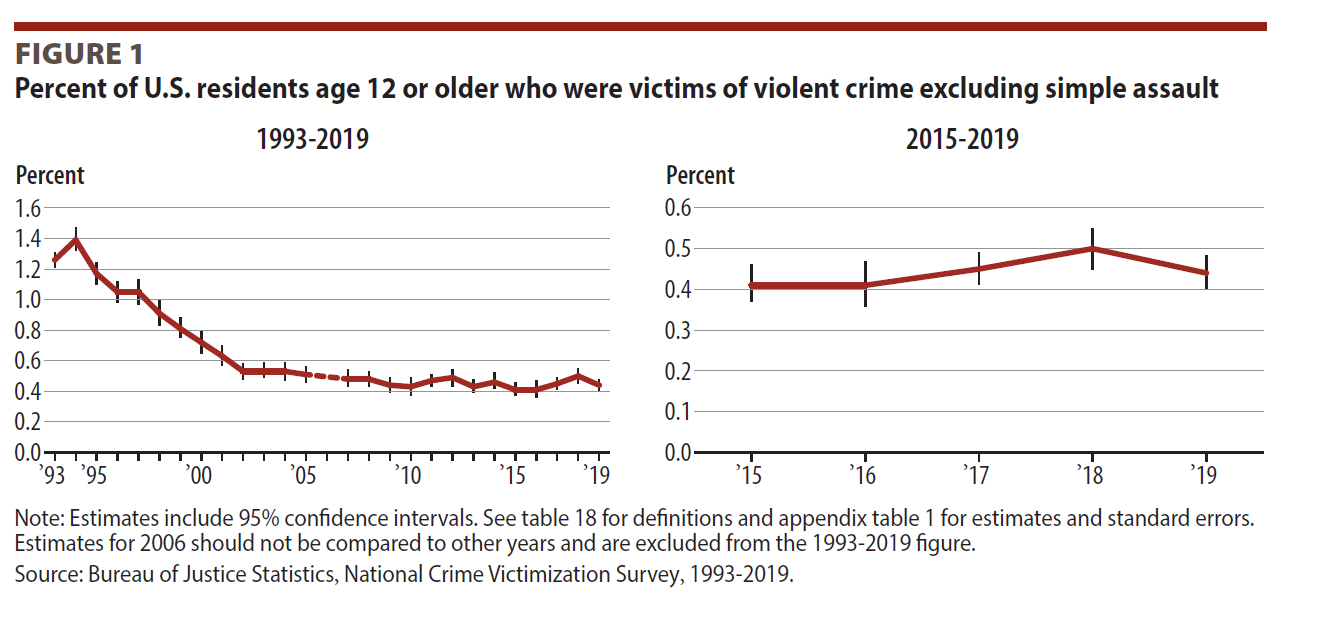

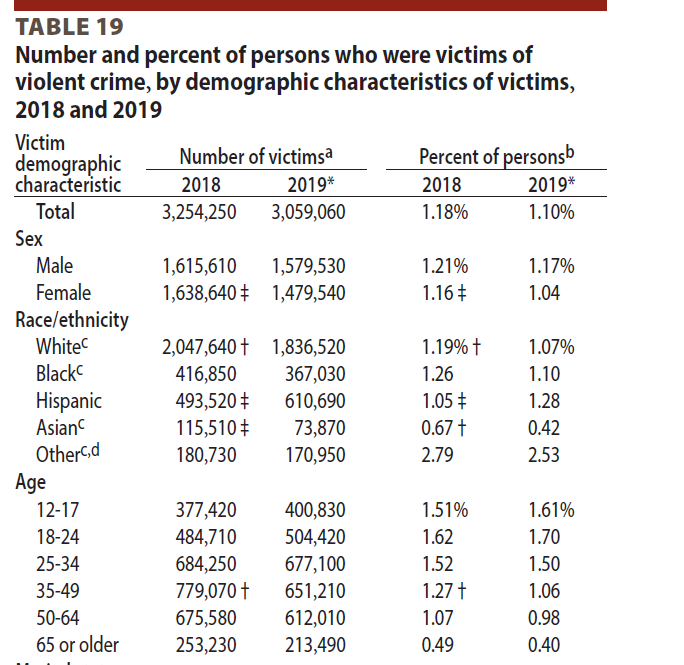

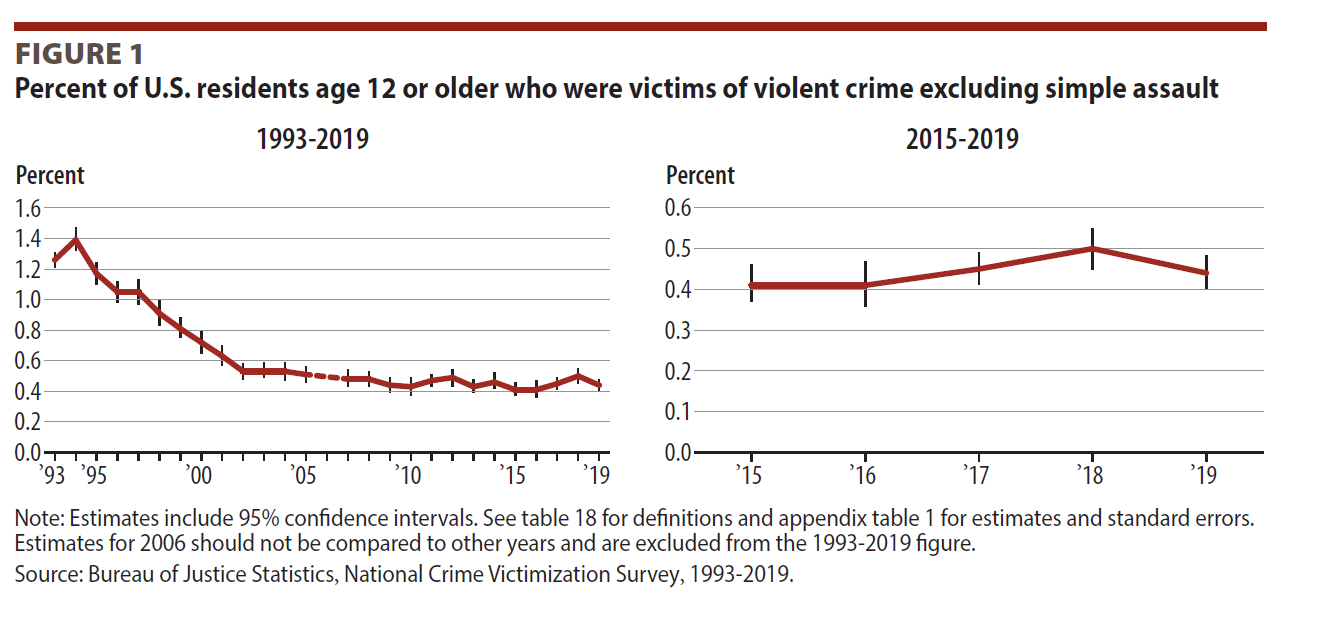

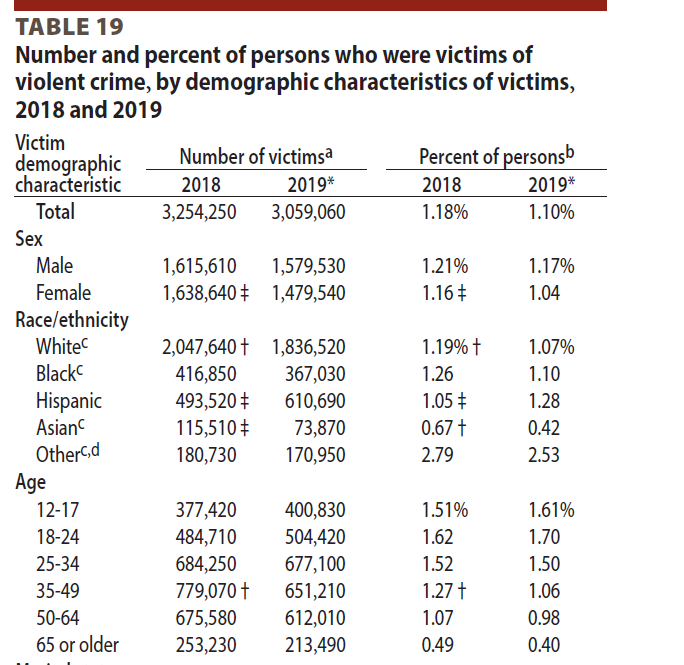

Just released: The 2019 National Crime Victimization Survey shows a small decline since 2018 and continuation of the longer-term crime drop that began in the mid-1990s.

Just released: The 2019 National Crime Victimization Survey shows a small decline since 2018 and continuation of the longer-term crime drop that began in the mid-1990s.

The Oregon State Penitentiary just “celebrated” its 150-year anniversary last week. 150 years is a long time in a west coast state; as a point of comparison, Oregon State University was founded in 1868, so while it is nearing the 150 year mark, the state’s oldest prison has been around longer than its land grant college.

The Oregon State Penitentiary just “celebrated” its 150-year anniversary last week. 150 years is a long time in a west coast state; as a point of comparison, Oregon State University was founded in 1868, so while it is nearing the 150 year mark, the state’s oldest prison has been around longer than its land grant college.

But should we celebrating the longevity of a state prison? As one of my inside friends and collaborators pointed out to officers on the inside: what is there to celebrate? Shouldn’t we instead consider our current prison system a massive failure, given that approximately 1 in 100 people are behind bars and multitudes beyond that are affected by their incarceration? And, if and when they get out, they will face the stigma of a criminal conviction, further limiting their life chances and opportunities for successful reintegration.

To add to the irony of this situation, the men incarcerated in the Oregon State Penitentiary were put on lockdown the day of the celebration so that the dignitaries could honor the anniversary without having to worry about having actual contact with prisoners (or “adults in custody” which is now the preferred label in the state). So, for the prisoners, the “celebration” of this anniversary kept them locked in their cells unable to work at their jobs, unable to go to classes or groups, and unable to go to the yard for exercise and fresh air.

I happen to like OSP a lot as far as prisons go, and I spend a good deal of time there working with the men inside. But, the 150 year mark feels like it should be a time to reflect and think about the future rather than celebrating a century and a half of men locked behind bars.

from The New York Times, article on “Momentum on Criminal Justice Repair“:

[The] bill would sentence most first-time, low-level, nonviolent drug offenders to probation rather than prison; give judges more discretion to grant leniency; create alternatives to prison, like drug-treatment and mental-health programs; reward prison contractors for reducing recidivism; largely end federal prosecution of simple drug possession; and confine mandatory-minimum sentences to high-level traffickers.

In a joint interview last week, I asked Mr. Sensenbrenner about his evolution. And he gave a frighteningly honest response for a man who has sat for decades on the House Judiciary Committee: “We really aren’t exposed to the practical aspect of the criminal-justice system, or what happens or doesn’t happen in the prisons.” So when he and Mr. Scott held hearings on the subject beginning in 2013, Mr. Sensenbrenner said, he got an “education.”

…The legislators’ praise for their own handiwork consisted of repeatedly calling it “evidence-based,” rather than just, right or moral. Which prompted a question: “Isn’t all legislation evidence-based?”

They laughed. Mr. Sensenbrenner said, “No! No! No!” Especially not with criminal-justice bills, Mr. Scott added, recalling the adage “No politician ever votes against a crime bill named after somebody” — meaning a victim. Now America will learn whether a nameless crime bill, defending faceless and unpopular prisoners, is a rare moon with a chance.

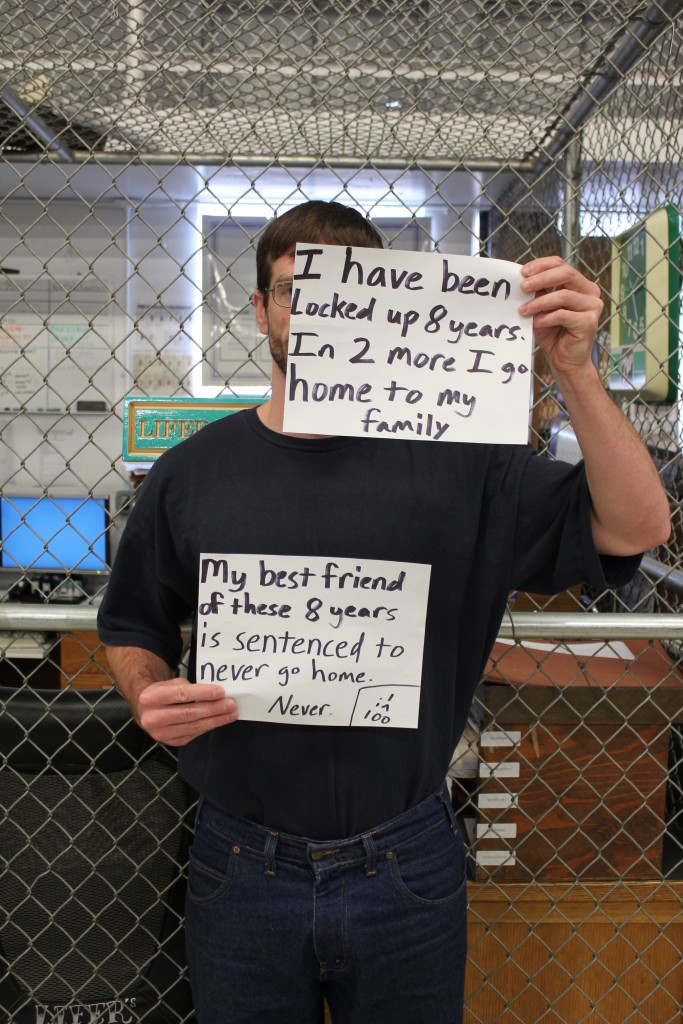

This piece was written by Trevor and is posted on our blog for the RISE UP! youth empowerment program at the Oregon State Penitentiary (www.riseuposp.com). The photo is of another prisoner, and is posted on the tumblr site: We Are the 1 in 100.

This piece was written by Trevor and is posted on our blog for the RISE UP! youth empowerment program at the Oregon State Penitentiary (www.riseuposp.com). The photo is of another prisoner, and is posted on the tumblr site: We Are the 1 in 100.

I wake up at 4:55 AM each and every morning. Why? Well, in part, because I can, because I have the freedom to choose at what time I’m going to start my day. This is not true of every day mind you, as many things can change an individual’s schedule or routine. That said, I get up that early, again in part, because when my door most often unlocks, at about 5:15 AM, I don’t want to be in the cell any more where I’ve been for the last number of hours.

I most often choose to eat plain oatmeal with peanut butter, (unless it’s Sunday when the chow hall typically serves eggs, potatoes and toast) because in part I don’t want to experience anymore of the chow hall that I reasonably have to, and because I can afford to eat oatmeal (at $1.00 per pound) and peanut butter (at $2.15 per 16 oz. container) for breakfast.

Work starts at 6:00 AM and I count myself as extremely fortunate to have what we call an industries job. This is an 8-hour a day, 5-days a week, job, in the penitentiary’s industrial laundry. We process linen from the surrounding hospitals, colleges, institutions, etc. Between 1 million and 1 and a half million pounds per month of linen gets processed through our facility. I work in the maintenance department, which is responsible for keeping the equipment running smoothly, maintaining operation of the machinery, scheduling down time for repairs, etc. This job also pays exceedingly well (comparably speaking) as instead of the average monthly income of around $45.00 I earn roughly $150.00 monthly. This has allowed me to maintain regular contact with family through phone calls at 0.16 per minute ($4.80 for a 30-minute phone call) purchase some items to make life more livable through supplementing the food provided from the chow hall with items from canteen / commissary, as well as pay off my restitution and court fees over the last 17-years of roughly $15,000.00 so that should I one day regain an opportunity to live in the community, I’ll be able to start that life without monetary debt.

Typically, around noon I’ll have lunch, which most often gets eaten in that place I’d rather not frequent, the chow hall. Our menu rotates every 3-months (by seasons) with few exceptions, and while that isn’t horrible for a couple of years, when you start passing decades by, it gets redundant and the desire to consume food outside of what gets offered day in and day out grows. I’ve come to think of what I eat as simply fuel.

Between 1 o’clock and 2 o’clock I’m off work and might try to get outside for some sunshine if I’m lucky enough, maybe some exercise, jog around the track or just walk some laps with someone who I need to catch up with for however long. Otherwise it’s reading, studying for work, educational purposes, etc.

Dinner is around 5 PM, that same chow hall that I’d most often rather not go to, however I don’t want to suggest that the food is so bad that we can’t eat it because that’s not the case, many here are well overweight, it’s simply the choices those individuals choose to make in how and what they consume, what level of activity they participate in, whether due to their abilities or basic drive, and what medical conditions may exist in their lives.

During the evening hours I try to write letters, read, call family and friends, maybe attend a function or fundraiser if I’m fortunate enough be involved in something of that nature, educational opportunities, youth outreach programs, etc. For many however, it’s nothing more than watching TV or staring at a blank wall. Again, I’m fortunate, both in my personal agency and my outlook on life.

When I’m asked about “what prison is like” I offer that it is an extremely lonely place, where every moment of every day is dictated for you, and where there’s tremendous opportunities for self-reflection. In the movies, on TV, and through media coverage, you see individuals that get swept up into the justice system and there’s this emphasis on the crime, the trial, entry into prison…then there’s a few scenes of portrayed prison, walking the yard with the tough guys, pumping iron, watching your back in the shower room, etc. and lastly this great experience of being released from prison, back to spending time with family and friends, BBQ’s in the summer-time, and so on and so forth. All very “event orientated” without the day-to-day experiences put on display. In part that’s because you can’t show the day-to-day loneliness, the feelings of exclusion, the feelings of shame and cowardice that accompany an individual’s incarceration. The realization that we’ve not only victimized our actual victims through whatever offense(s) we’ve committed, but we’ve additionally victimized our own families, the community, society as a whole, our friends and loved ones, everyone in fact that we come in contact with. The courts, lawyers, judges, prosecutors, juries, corrections officers, police, detective…and the list goes on and on!

So what do I hope to get across here? For starters, we as prisoners are human beings, individuals who have failed society for whatever reasons and though no excuse relieves us from our poor life decisions, without hope and help to be better people, without redemption, society is all but lost in its entirety through our bad behaviors. In a discussion group with college students not long ago, after describing some of the opportunities available here in the penitentiary in which I reside, one student asked me if we as prisoners deserved such opportunities. I paused before answering that society deserves us to have such opportunities, because if we do not come out of prison with more skills and a more productive mindset then we came in with, we are destined to once again fail society.

This is a day in the life of a prisoner…one who considers himself extremely fortunate in countless ways and for just as many reasons.

With full approval of the administrative team at the Oregon State Penitentiary, I’ve started and will be curating a blog for the RISE UP! youth empowerment program that is largely run by Lifers in the prison. The men of RISE UP! (Reaching Inside to See Everyone’s Unlimited Potential) hope to use the blog to give a unique perspective to youth who may be struggling or who could simply benefit from advice and encouragement from men who may have made bad decisions in their younger days but are now working to better themselves and the community. The men of RISE UP! work with Oregon high schools, including students as well as concerned teachers, parents, and counselors; youth outreach programs; community groups; and religious organizations. Their desire is to end the cycle of incarceration, especially for youth.

With full approval of the administrative team at the Oregon State Penitentiary, I’ve started and will be curating a blog for the RISE UP! youth empowerment program that is largely run by Lifers in the prison. The men of RISE UP! (Reaching Inside to See Everyone’s Unlimited Potential) hope to use the blog to give a unique perspective to youth who may be struggling or who could simply benefit from advice and encouragement from men who may have made bad decisions in their younger days but are now working to better themselves and the community. The men of RISE UP! work with Oregon high schools, including students as well as concerned teachers, parents, and counselors; youth outreach programs; community groups; and religious organizations. Their desire is to end the cycle of incarceration, especially for youth.

I’ll post testimonials and short essays written by the members of RISE UP! to the blog as regularly as possible, and we hope anyone caring for teenagers and young people will find the advice and honesty in their words helpful. Criminologists, you may find their stories, perspective, and advice useful in your own thinking and teaching, as well. The guys want to do everything they can from within the prison to help young people avoid making the kinds of mistakes and decisions that may one day get them in serious trouble. Please share the RISE UP! blog (www.riseuposp.com) with anyone who you think might be interested. If you have questions or comments for the men of RISE UP!, please feel free to put them on the RISE UP! blog. We’ll respond as quickly as possible, but it may take several days as we work through the prison’s channels for communication.

The RISE UP blog is a great, more in-depth companion piece to our We are the 1 in 100 site, which features photos, facts, and brief testimonials from my Inside-Out students (both those inside the prison and the youth correctional facility and the Oregon State University students who shared class with them) over the past several years. Please check out both sites, if you have the time. The men inside have a lot of great positive advice and life lessons to share.

I’ve written quite a bit about my Inside-Out classes and my work teaching and volunteering in prisons and youth correctional facilities on this blog. I’ve shared less about my efforts to connect my on-campus classes to those same facilities and the individuals living within them through service-learning projects, volunteer opportunities, and interactive community impact meetings. These activities affect a much larger number of my university students and can be extremely powerful.

I’ve written quite a bit about my Inside-Out classes and my work teaching and volunteering in prisons and youth correctional facilities on this blog. I’ve shared less about my efforts to connect my on-campus classes to those same facilities and the individuals living within them through service-learning projects, volunteer opportunities, and interactive community impact meetings. These activities affect a much larger number of my university students and can be extremely powerful.

I recently published an article on “‘A Lot of Life Ahead’: Connecting College Students with Youth in Juvenile Justice Settings through Service-Learning,” which is freely available in the Fall 2014 issue of Currents in Teaching and Learning. In the article, I discuss some of the challenges and rewards of trying to organize 45-50 university students to lead interactive sessions with incarcerated youth in a short 10-week quarter and offer advice for other instructors who might be inspired to try it. There’s always quite a bit of chaos involved, but the positive outcomes for all involved make it very worthwhile.

Several of my Oregon State University students are graduating this week, and at least four of them are going into jobs working in state youth correctional facilities. By my count, I’ll have at least eight former students working as staff members in Oregon Youth Authority facilities, with virtually all of them finding this career interest through the direct exposure to the system in my classes. I’m really proud of these students and the fact that I was able to help kindle their passion to work with troubled youth. For me, that’s the real heart of Public Criminology.

“Are you for or against?” the correctional officer asked me at the gate.

“Against,” I responded. I had driven nearly two hours through the Georgia countryside to attend a vigil at Georgia State Diagnostic and Classification Prison near Jackson, where the state’s male death row inmates are housed. The state planned to execute Warren Lee Hill at 7:00pm that night. The significance was not lost on me as I drove past beautiful, columned antebellum homes along Georgia’s “Antebellum Trail” (a series of towns spared by General Sherman’s torches in 1864), on my way to a vigil protesting the state’s execution of an intellectually disabled black man.

The officer looked at my driver’s license, wrote down my name and my license plate number on a notepad and directed me to turn left into a red clay dirt patch where other cars were parked. The road straight ahead, leading to the prison facility, was dotted with orange road barriers. As I turned off the main road and in to the makeshift parking area, several more officers dressed in full riot gear directed me with flashlights to a parking spot underneath tall pine trees. The officers instructed me to take everything I needed from my car because I would not be allowed back in after the drug-sniffing dogs had been through it.

I’d never attended a death penalty vigil before, much less one held outside the prison where the execution would take place. I’d visited youth and adult prisons many times in my professional life before grad school and while conducting research, so the rigors of security were not new. A few particulars were markedly different, though. I’d never had drug-sniffing dogs run around and through my vehicle before. Fine looking canines that they were, I held my breath as one seemed to linger a while in my front seat. The correctional officers were courteous at every turn, taking a bit of the edge off the feeling of violation inherent in such scrutiny of myself and my belongings. It was clear to me that had done this before; in fact they had just a few weeks prior at Georgia’s first execution in 2015.

Once the dogs were done with my car I was free to join my fellow vigil-holders in our designated corral. And by corral I mean a semi-grassy area roped off with a picnic table holding a cooler of water provided by the prison in the center. I was grateful to see a biffy nearby, just in case the wait was long. There, people were gathered, chatting and waiting with signs bearing slogans such as “Not in my name” and “Yes, there are alternatives to the death penalty.” A correctional officer stood at the entrance to the corral to monitor our comings and goings. There was a second corral available nearby for anyone “for” the execution. No one stood there that night, though I was told that the previous execution had a solid showing of police officers; the executed man – Andrew Brannan, a Vietnam veteran who claimed to suffer from PTSD – was convicted of killing a sheriff’s deputy in 1998.

We were far enough away from the prison itself that I was unable to see the building through the trees. Our only clue as to what was happening inside the facility would (eventually) come from vans driving down the road carrying witnesses and family members from the execution (to be followed later by the coroner’s van).

Soon after I arrived, we were briefly ushered out of the corral to stand for pictures for the media. A few of my fellow protesters stayed to give comments. Clearly not the occasion for a smile, I stood awkwardly, at the back of the group, channeling as best I could my stoic ancestors’ smile-free family photos (fortunately, the photo featured here excludes me).

As 7:00pm arrived, the vigil organizers – many were affiliated with Episcopal or Catholic churches (clerical collars were in abundance) – invited us all to join in a time of prayer and reading the names of those previously put to death. A representative from Georgians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty informed us that the Supreme Court had just declined to intervene on Lee’s behalf, leaving no further obstacles to the execution.

We stood in a circle, at points holding hands. Prayers were said – including the Lord’s Prayer. Although familiar from my Lutheran upbringing, saying the words in this particular context carried a different meaning (e.g. “forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us”). I managed to choke out most of the words to “Amazing Grace,” our voices echoing off the pine trees surrounding our circle, the death house obscured from view but very present in mind.

As the group took turns reading the names of the people Georgia has executed since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976, I read names and dates of death for numbers 40-42:

John Washington Hightower: June 26, 2007

William Earl Lynd: May 6, 2008

Curtis Osborne: June 4, 2008

After the formal vigil concluded, we stood in our corral, waiting. Although I had dressed relatively well for the chilly 30-degree January Georgia night, I stamped my feet periodically to keep the feeling in my toes.

At about 8:10pm, we spotted headlights from several white vans making their way down the road from the prison. Warren Lee Hill had been dead since 7:55pm.

One of the witnesses to the execution came over to the corral to describe how Mr. Hill had died – no final words, peaceful. A pastor from a local church spoke about his conversations with Mr. Hill, and his belief in Mr. Hill’s reform. A few minutes later, a correctional officer gently informed us it was time to go.

My reasons for attending the vigil were both personal and professional. I’ve never lived in a death penalty state before, so I went in part because I was curious. As a private citizen, I’m opposed to the death penalty on humanitarian and religious grounds. As a criminologist, I know that the practice is an ineffective deterrent to crime, arbitrarily applied, and racially biased (see also this graph); not to mention its financial costs and the inherent risk of putting innocent people to death. I approach the subject in my undergraduate criminology classes knowing that many of my students may be in favor of the death penalty, and I respect their personal opinions. But I never shy away from presenting them with the evidence provided by social science research regarding the death penalty’s lack of deterrent effect and its problematic implementation along racial lines.

As I write this, executions in Georgia are on hold pending an investigation into the drug cocktail the state uses to perform lethal injection. Just a month after Mr. Hill’s death, the state was set to execute its first woman since Lena Baker in 1945. Kelly Gissendaner’s execution was halted at the last minute on March 2nd when the drugs to be injected appeared “cloudy.” An additional execution scheduled for a week later was also postponed. This development obviously calls to mind the botched execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma on April 29, 2014. Ms. Gissendaner has since filed a lawsuit against the Georgia Department of Corrections, citing cruel and unusual punishment brought on by the hours of fear and uncertainly prior to her execution’s postponement, as well as ongoing questions about Georgia’s ability to provide a humane death.

For more on the death penalty in the United States, listen to TSP’s Office Hours podcast with David Garland.

When the news came from Ferguson on November 24th, it was hard to know what to do. Each of us possesses some pertinent expertise, whether we study violence, law, race, or criminal justice and injustice. But how and when should we engage? The streets were alive with protesters, police officers, and journalists. The President was calling for calm, which was itself a polarizing message. And Facebook feeds flowed with horrifying videos, rage, and invective, as many were “defriending” and “unfollowing” one another until their social networks were fully purged or converted.

Public scholars can and should step up in such highly-charged political moments, but there was little room to maneuver in those first few days. A dispassionate rendering of cold social facts – on the legal intricacies of grand jury indictment, for example – would ring hollow to those who saw the events in clear moral terms. A straightforward presentation of a pertinent research study – on the effectiveness of police body cameras, for example – would redirect energy and attention away from larger questions. And, to the extent we could actually penetrate the teeming information space, our statements would be reduced to 140-character factoids and channeled to those predisposed to agree with us already. How can we do good public work under such conditions?

In the tense days and nights after the indictment announcements, sociologists such as Michael Eric Dyson and Doug Hartmann made insightful big-picture contributions. Some of us wrote op-eds or gave interviews, others spoke at demonstrations or held teach-ins, and many more revamped our regular teaching and research activities. Like many of you, I found myself in several community forums, most recently with a sitting judge and a television reporter who would moderate our discussion. The talk had been scheduled for months as a wonky “nuts and bolts of justice reform” discussion, but the sudden surge of interest in crime and punishment reshaped our agenda. It would have been foolish, if not impossible, to ignore the protests and issues occurring right outside the door. Interest was high. We moved the event to a larger hall when we reached capacity and we recorded the proceedings for later broadcast. As I looked around the racially and socially diverse crowd of journalists, students, lawyers, teachers, police officers, formerly incarcerated people, and community members, I knew that dozens if not hundreds of my colleagues were similarly engaged in their communities. I claim no special expertise on these topics or events, but I share these personal reflections and suggestions in hopes of encouraging other section members who might wish to engage the public.

Position and Language

When speaking with a public audience, I try to remember that there are other experts in the room. For example, a middle-aged white guy like me has little authority or legitimacy regarding the subjective experience of interacting with police as a young African American in the central city. Put simply, many in attendance did not want or need me to lecture to them about how their communities are policed. So my job was to give due attention to race and justice while also acknowledging the real limits of my perspective and the research evidence I would cite. Thinking a personal story might help, I opened by acknowledging the #BlackLivesMatter and #CrimingWhileWhite campaigns and briefly noting my own juvenile arrests – and how the “judicious and humane discretion” of three Minnesota police officers was so important in my life that I thanked them by name in my dissertation acknowledgements. After repeated exposure to the Michael Brown and Eric Garner videos, few in the audience would have argued that men of color have been getting the same breaks that I received. As importantly, few would have argued against providing the same sort of breaks to all young people. Yet framing the issue in this way also helped make such points without bashing or demonizing those police officers – several of them my former students — who showed up at the forum.

This was not the night for a PowerPoint presentation, as personal stories are often more effective than statistics in helping audiences evaluate and reframe their image of crime and justice. I also called out Emily Baxter’s WeAreAllCriminals.com. Using evocative images and personal accounts, WAAC shows the blurriness of the criminal/non-criminal distinction. Terminology plays a similar role in public scholarship, where the wrong descriptor can quickly alienate half the audience. I try to use simple, neutral language to facilitate discussion, addressing people formally (e.g., as Ms. Johnson or Judge Castro, rather than as Angie or Lenny). In such forums, identifiers such as “police officer” or “formerly incarcerated” are more helpful and precise than terms like “cop” and “offender.”

Content and Context

Academics sometimes try to teach a whole semester’s worth of material in an hour, which dramatically exceeds anyone’s ability to process new information. I try to identify three to five key points and to make sure that they are well-supported in the literature. That is, that they are “near-consensus” areas in our field that the public might not yet appreciate. That night, I called out: (1) Tom Tyler’s work on procedural justice, and how treating people with dignity and respect engenders greater trust and legitimacy, regardless of the outcome of a citizen’s encounter with the criminal justice system; (2) social-psychological research on implicit bias, which shows that the great majority of Americans, including police officers and professors, hold unconscious group-based biases that affect our behavior; (3) a few well-chosen statistics on the basic race-specific rates of arrest and incarceration in our community; and, (4) the proportion of these arrests that are for low-level offenses that rarely result in prosecution or conviction. Local evidence is critical because the audience is far more engaged in practices close to home (and more likely to dismiss or discount bad things that happen elsewhere). Public criminology can also provide an important myth-busting function in such cases. For me, this meant calling out states like Minnesota and Wisconsin for having the nation’s worst racial disparities in correctional populations – a difficult but essential truth for the audience to grasp. Context is also important for drawing local, national, and international comparisons. For example, I explained how my home state was admirably stingy with prison beds, but profligate in putting people on very long probation terms.

Hope and Questions

Public events, to a far greater extent than academic talks, should leave the audience with a sense of efficacy, or at least hope for real change. I made sure to note that after four decades of rising incarceration, that criminal punishment had finally begun a modest decline. And, of course, that our community and the nation had enjoyed a 50 percent crime drop over the past two decades. To put this drop in perspective, I explained how this meant a decline from 100 Minneapolis murders in 1995 to about 40 the past few years. Nationally, I pointed to bipartisan reform efforts such as the REDEEM Act, cosponsored by Senators Corey Booker and Rand Paul. Locally, I identified bipartisan reforms such as the new Minnesota expungement law and a new ban-the-box provision that bars organizations from asking about criminal records on job applications, but permits them to inquire at the interview stage. I also tackled issues in my own area of research expertise, including local challenges to felon disenfranchisement and the broader problem of “piling on” so many collateral sanctions that they become criminogenic. In particular, I described recent testimony on behalf of six “model probationers,” who were hauled into court and charged with new felonies because they had voted while still “on paper.” A broad coalition was assembling to challenge the voting ban (including the district attorney charged who prosecuted those cases) and several audience members approached me after the event to ask how they could get involved. Finally, I spoke about the costs of diminished trust in the criminal justice system, including Todd Clear and Natasha Frost’s argument that the discretion to make back-end sentencing adjustments can help curb excess or gratuitous punishment – even, or especially, for those serving long sentences for violent crimes.

Public events work best when audience members have a chance to engage the speakers, and we received an impressive range of audience questions that evening. When asked about the prospects for a new social movement around criminal justice reform, I could applaud the efforts of students — and the members of this section — to shine a brighter light on crime, law, and justice in the contemporary United States. As a medical school colleague is fond of saying, sunshine can be a marvelous disinfectant. So too can public criminology.

For further reading, see Doug Hartmann’s Ferguson, the Morning After; Insights on Crime and Punishment from a Judge and a Sociologist, and Public Criminologies (with Michelle Inderbitzin).

Reprinted from Crime, Law & Deviance News, FALL/WINTER 2014 -2015

Newsletter for the Crime, Law & Deviance section of the American Sociological Association

Once again, my Inside-Out students from Oregon State University and Oregon State Penitentiary have contributed thoughtful, insightful, and sometimes painful submissions to the We are the 1 in 100 website, representing the 1 in 100 people in the United States who are currently behind bars, and the many, many more people in the community who care about them and are affected by mass incarceration.

I have a personal stake, here – I’m fond of these faces and proud of their work and their courage – but, if you check out the site (representing 3 years and 7 different college classes), I think you will find it a moving and educational experience, well worth your time.

The Minneapolis Star-Tribune reports that a group of “sex offenders” are registering to vote and plan to run for elected office. I put “sex offenders” in quotations because these voters and office-seekers are not currently under supervision for any crime. Instead, they are “civilly committed,” which means that they have either already completed their criminal sentences or, as is the case for over 50 clients, they were never charged as an adult for a sex offense. Although they are euphemistically called “clients” rather than prisoners, most will likely be locked away forever.

How can we continue to lock someone up after they have done their time? The state Department of Corrections generally reviews those convicted of sex crimes at the end of their sentences, referring those deemed dangerous to county attorneys, who may then file a petition for commitment with the district courts. Although civil commitment is rare in many places, Minnesota does this a lot — there are currently about 700 such clients in two secure facilities in the state. How many are released? The program has been in operation for over 20 years, but only 2 people have ever been provisionally discharged from the program.

In a federal class action lawsuit, U.S. District Court Judge Donovan Frank has raised serious questions about the program’s constitutionality. To date, however, the residents/inmates have received little hope or relief and the trial has been pushed back until next year. Given the hyper-stigma surrounding sex offending, few brave souls will act or advocate on behalf of the people in the program. So, they are doing their best to advocate for themselves and to work within what is increasingly acknowledged as a broken system — exercising their rights to vote and seek office.

While the article by Chris Serres and Glenn Howatt contains a wealth of information, they omitted one other factoid that speaks to the program’s sustainability: according to the state Department of Human Services, the per diem cost of the program is $341. This is approximately $125,000 per inmate per year, or roughly four times the cost of the $86 per diem at the state’s correctional facilities. As law professor Eric Janus once put it, “The option of doing nothing would not be responsible from either a legal or fiscal perspective.”