When you take a course of antibiotics to zap a bacterial infection, you can also lay waste to a lot of healthy bacteria that your body really needs. And once you’ve wiped out the healthy flora in your gut, you’re vulnerable to nasty bacteria such as Clostridium Difficile, which brings symptoms ranging from severe diarrhea to life-threatening colon problems. Though I’m skeptical-bordering-on-terrified of organicist arguments in sociology, hearing a talk by Minnversity colleague Mike Sadowsky on “C. diff.” brought some parallels in social research to mind. Before proceeding, I should acknowledge the obvious “ick factor” in this post, but bear with me a moment.

When you take a course of antibiotics to zap a bacterial infection, you can also lay waste to a lot of healthy bacteria that your body really needs. And once you’ve wiped out the healthy flora in your gut, you’re vulnerable to nasty bacteria such as Clostridium Difficile, which brings symptoms ranging from severe diarrhea to life-threatening colon problems. Though I’m skeptical-bordering-on-terrified of organicist arguments in sociology, hearing a talk by Minnversity colleague Mike Sadowsky on “C. diff.” brought some parallels in social research to mind. Before proceeding, I should acknowledge the obvious “ick factor” in this post, but bear with me a moment.

As Dr. Sadowsky explained, one successful treatment for recurrent C. diff infections involves fecal transplantation – essentially implanting a donor’s stool sample in a recipient to repopulate the healthy colonic flora and restore bacterial balance. Within a very short time, the donor’s gut flora is typically brought back to healthy equilibrium. Now that might sound icky (even when said sample is freeze-dried), but it is way less icky than surgical treatments like colectomy. What really got me thinking was my colleague’s big-picture conclusion that much of the past century of U.S. research in this area had been devoted to isolating and zapping the bacterial delinquents, while much of the next century seems devoted to restoring the whole to healthy balance. And, if I understand things correctly, it turns out that the latter approach is actually a lot simpler than specifying, modeling, and manipulating the complex interactions among myriad bacteria that may be “good” or “bad” depending on the particular combination and circumstance.

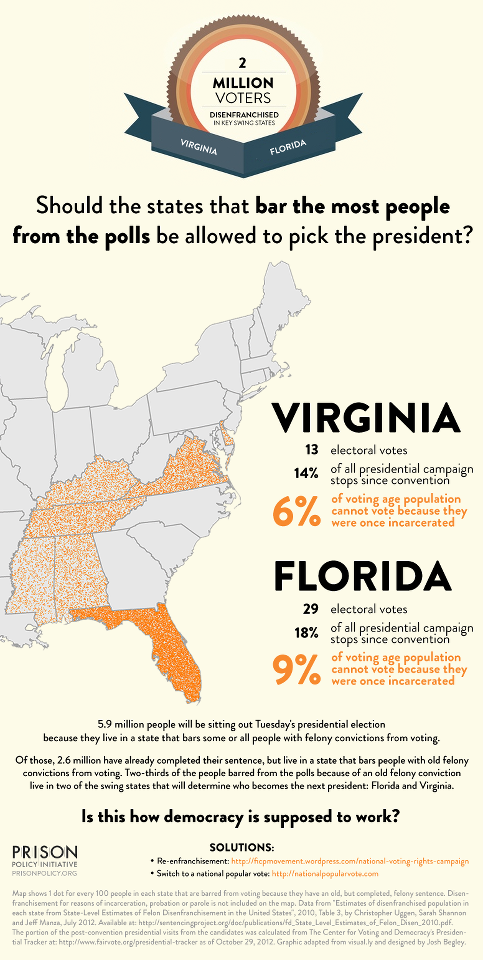

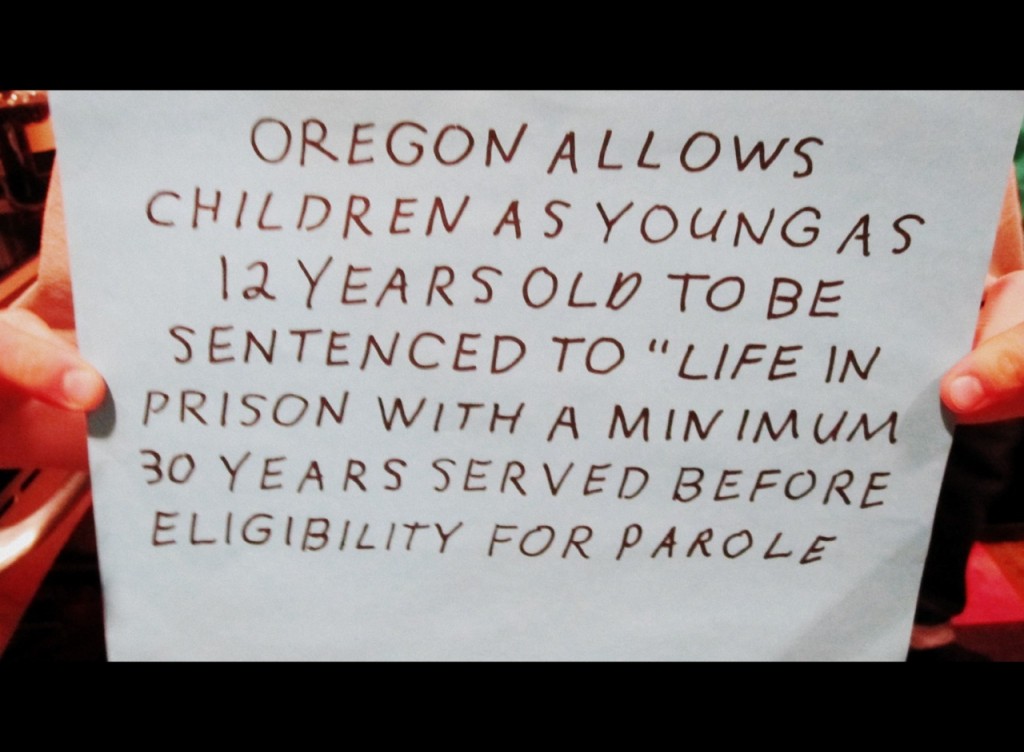

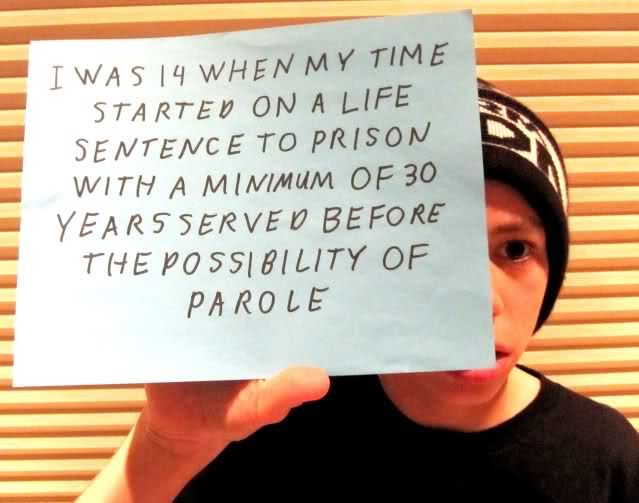

Of course, certain Ghosts of Sociology Past, Present, and Future think about societies in quite similar ways. No, people aren’t bacteria and communities aren’t intestines, but you don’t have to be a functionalist or an organicist to draw some basic analogies. For example, as William Julius Wilson points out, it is the social isolation of the urban poor that exacerbates the challenge of redressing imbalances and (re)building the institutions needed for basic community functioning. More generally, social interventions, like medical interventions, sometimes bring their own pathologies or iatrogenic effects. Like the overprescription of antibiotics behind the apparent C. diff epidemic, the grand American experiment with racialized mass incarceration, has had untold effects on individuals, families, and communities that are only now coming into focus.

I won’t speculate here about how to restore social systems to healthy balance, but some of us try to at least consider such questions in our research. In some cases, this involves calling out the problems associated with attempts to isolate and zap our more delinquent members. In others, it involves identifying and assessing viable alternative approaches to reducing harm — regardless of any potential “ick factors” that might be associated with our research.