More social scientists are pointing out that the computer algorithms that run so much of our lives have our human, social biases baked in. This has serious consequences for determining who gets credit, who gets parole, and all kinds of other important life opportunities.

It also has some sillier consequences.

Last week NPR host Sam Sanders tweeted about his Spotify recommendations:

Y’all I think @Spotify is segregating the music it recommends for Me by the race of the performer, and it is so friggin’ hilarious pic.twitter.com/gA2wSWup6i

— Sam Sanders (@samsanders) March 21, 2018

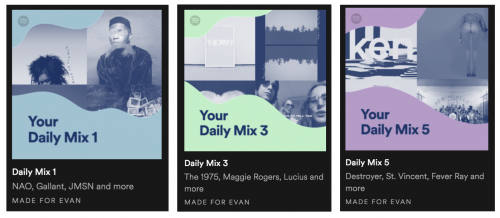

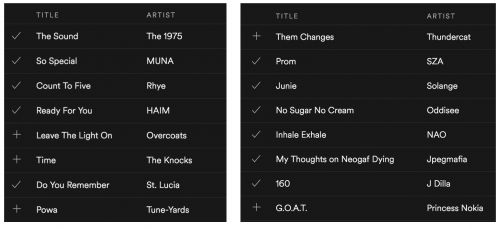

Others quickly chimed in with screenshots of their own. Here are some of my mixes:

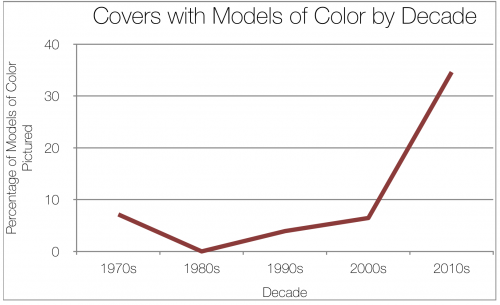

The program has clearly learned to suggest music based on established listening patterns and norms from music genres. Sociologists know that music tastes are a way we build communities and signal our identities to others, and the music industry reinforces these boundaries in their marketing, especially along racial lines.

These patterns highlight a core sociological point that social boundaries large and small emerge from our behavior even when nobody is trying to exclude anyone. Algorithms accelerate this process by the sheer number of interactions they can watch at any given time. It is important to remembers the stakes of these design quirks when talking about new technology. After all, if biased results come out, the program probably learned it from watching us!

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.