Flashback Friday.

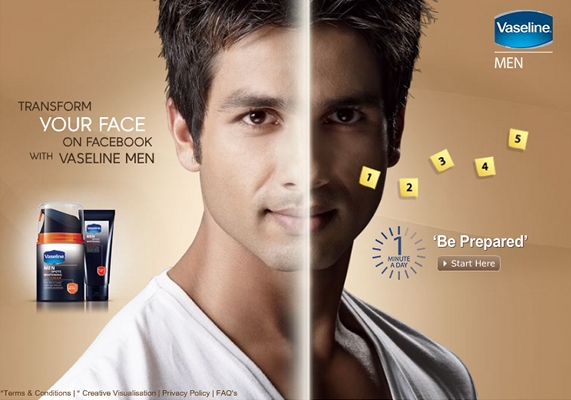

Previously marketed to women, skin lightening, bleaching, and “fairness” creams are being newly marketed to men. The introduction of a Facebook application has triggered a wave of commentary among American journalists and bloggers. The application, launched by Vaseline and aimed at men in India, smoothes out blotches and lightens the overall skin color of your profile photo, allowing men to present a more “radiant” face to their friends.

The U.S. commentary involves a great deal of hand-wringing over Indian preference for light skin and the lengths to which even men will go to get a few shades lighter. Indians, it is claimed, have a preference for light skin because skin color and caste are connected in the Indian imagination. Dating and career success, they say further, are linked to skin color. Perhaps, these sources admit, colorism in India is related to British colonialism and the importation of a color-based hierarchy; but that was then and, today, India embraces prejudice against dark-skinned people, thereby creating a market for these unsavory products.

The obsession with light skin, however, cannot be solely blamed on insecure individuals or a now internalized colorism imported from elsewhere a long time ago. Instead, a preference for white skin is being cultivated, today, by corporations seeking profit. Sociologist Evelyn Nakano Glenn documents the global business of skin lightening in her article, Yearning for Lightness. She argues that interest in the products is rising, especially in places where “…the influence of Western capitalism and culture are most prominent.” The success of these products, then, “cannot be seen as simply a legacy of colonialism.” Instead, it is being actively produced by giant multinational companies today.

The Facebook application is one example of this phenomenon. It does not simply reflect an interest in lighter skin; it very deliberately tells users that they need to “be prepared” to make a first impression and makes it very clear that skin blotches and overall darkness is undesirable and smooth, light-colored skin is ideal. Marketing for skin lightening products not only suggests that light skin is more attractive, it also links light skin to career success, overall upward mobility, and Westernization. Some advertising, for example, overtly links dark skin with saris and unemployment for women, while linking light skin with Western clothes and a career.

The desire for light skin, then, isn’t an “Indian problem” for which they should be entirely blamed. It is being encouraged by corporations who stand to profit from color-based anxieties that are overtly tied to the supposed superiority of Western culture. These corporations, it stands to be noted, are not Indian. They are largely Western: L’Oreal and Unilever are two of the biggest companies. The supposedly Indian preference for light skin, then, is being stoked and manufactured by companies based in countries populated primarily by light-skinned people. As Glenn explains, “Such advertisements can be seen as not simply responding to a preexisting need but actually creating a need by depicting having dark skin as a painful and depressing experience.”

Before pitying Indian seekers of light-skin, condemning the nation for colorism, or gently shaking our heads over the legacies of colonialism, we should consider how ongoing Western cultural dominance (that is, racism and colorism in the West today) and capitalist economic penetration (that is, profit through the cultivation of insecurities around the world) contributes to the global market in skin lightening products.

Originally posted in 2010; crossposted at BlogHer.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.