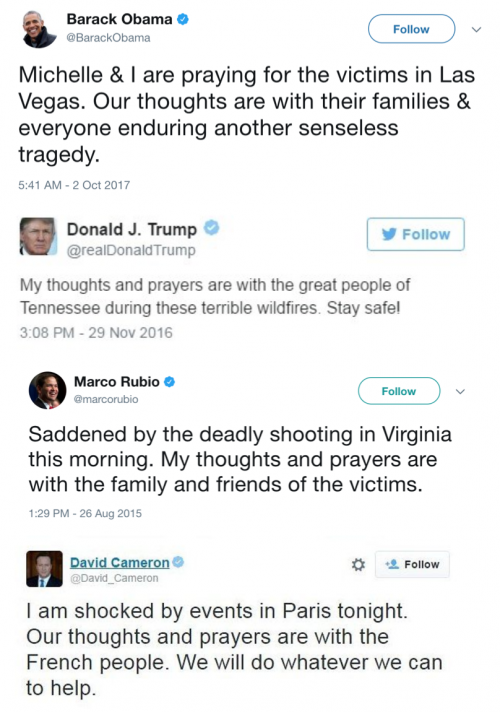

The harrowing mass shooting in Las Vegas this week is part of a tragic pattern, and it raises big questions about how we deal with such tragedies in public life. In the face of such horror, many people rightly turn to their deep convictions for comfort and strength, and their leaders are no different. Referencing religion is a common choice for politicians, especially in troubling times. Experimental evidence shows these references draw voters in, but lately it seems like the calls for comfort may have gotten a little…rehearsed.

For a growing number of Americans, calls for “thoughts and prayers” ring especially hollow. About a fifth of the U.S. population has no religious affiliation, and new experimental research shows we may be drastically underestimating the number of atheists in the population as well. Despite these trends, we don’t often seen direct challenges to religious beliefs and practices in policy debates. Healthcare reform advocates don’t usually argue that we should keep people alive and well because “there probably isn’t an afterlife.” While the battle to legalize same sex marriage discussed the separation of church and state, we didn’t see many large advocacy groups arguing for support on the grounds that biblical claims simply weren’t true.

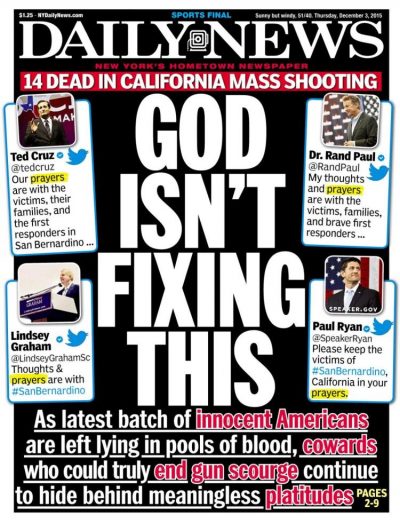

In lieu of prayer, calls for concrete action on gun control in the face of mass shootings are a new challenge to these cultural norms. In the wake of the 2015 San Bernardino shooting, the New York Daily News ran this cover:

Now, in press conferences and on the floor of Congress, more political leaders are openly saying that thoughts are prayers are not enough to solve this problem. Sociologists know that the ways we frame issues matter, and here we might be seeing a new framing strategy emerging from the gun control debate that could reshape the role of religion in American politics in the long term.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.