As fun as it has been to watch former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz announce a possible presidential bid and get ratioed on Twitter, his candidacy also says a lot about our deeper assumptions on wealth and politics.

From Citizen’s United to classic sociological works like Who Rules America, we know that wealthy interests have long influenced U.S. politics. This influence doesn’t just happen behind the scenes, though. It also shapes our thinking about who is qualified to run the show. Thorstein Veblen’s “conspicuous consumption” and Max Weber’s “Protestant ethic” both point out the public work that wealth does when people use it as a shortcut to indicate either merit or morals. Candidates like Donald Trump use these assumptions effectively by arguing that business savvy shows their qualification for public service.

Over on Montclair SocioBlog, Jay Livingston took a look at Schultz’s old school language on being a “person of means,” rather than a billionaire. This euphemism was especially interesting to me, because it shows how candidates with wealth also try to have it both ways. Schultz’s implicit argument is not that different from Trump’s: his wealth and business success make him qualified to run on a platform of fiscal responsibility and independence from party ideology. But in a changing political climate where some say “every billionaire is a policy failure,” drawing attention to this wealth can also be a political liability.

So, do people actually trust the rich to govern? A quick look at some survey data suggests there’s a pretty sizable partisan gap here. The American Mosaic Project asks people whether they think others from a variety of social groups share their vision of American society. This general question can tell us a lot about which groups people think are “like them,” a good proxy for trust and tolerance.

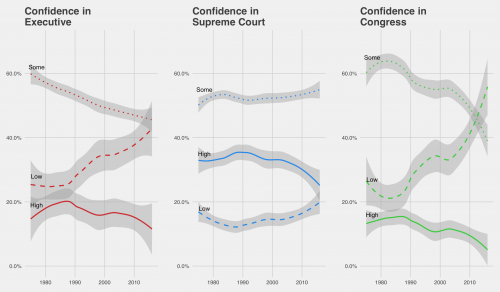

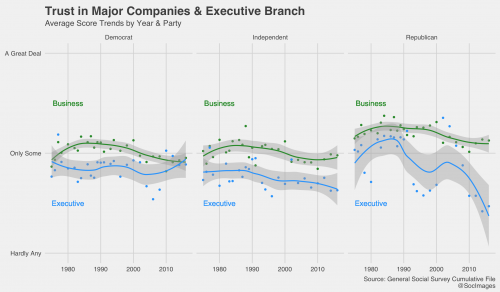

In this sample from 2014, Republicans had a higher average affinity with the rich than Democrats. We can also look the question a different way in the General Social Survey, which has been asking people about their trust in the Executive Branch of government and in major corporations for years.

Here again, these trends show elevated trust for in big business among Republicans, along with much more fickle attitudes toward the Executive Branch depending on who is in power. While people tend to trust business more than the government here, these quick snapshots also suggest that stronger trust in business and wealth tacks pretty closely to typical party politics. With more candidates on the left starting to question why we trust the rich to govern, this relationship might get stronger and keep wealthy independent candidates stuck in the middle. Successful business leaders might seem like good candidates for government, but they also need to do their market research first.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.