What works

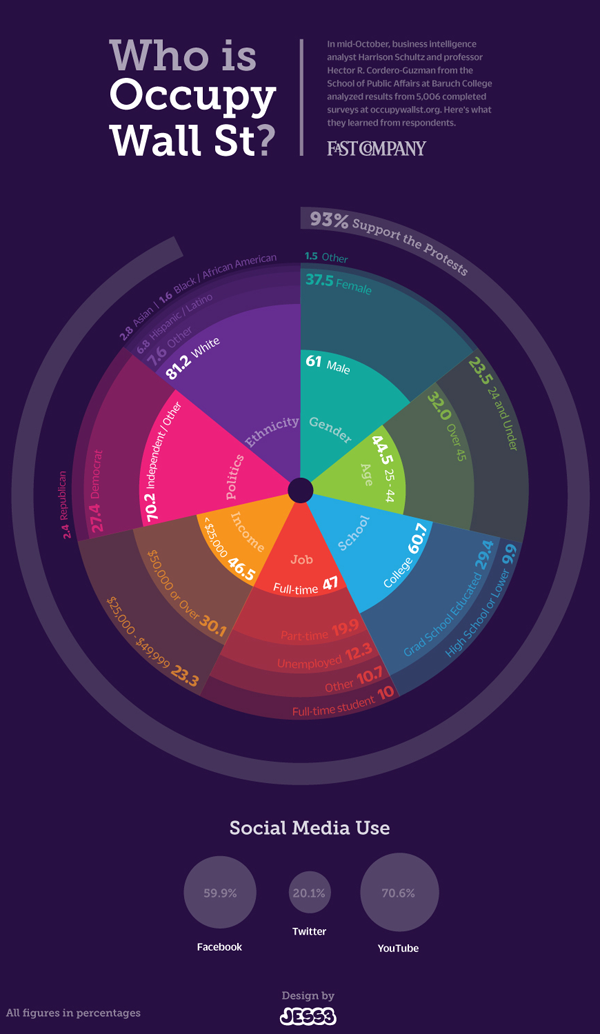

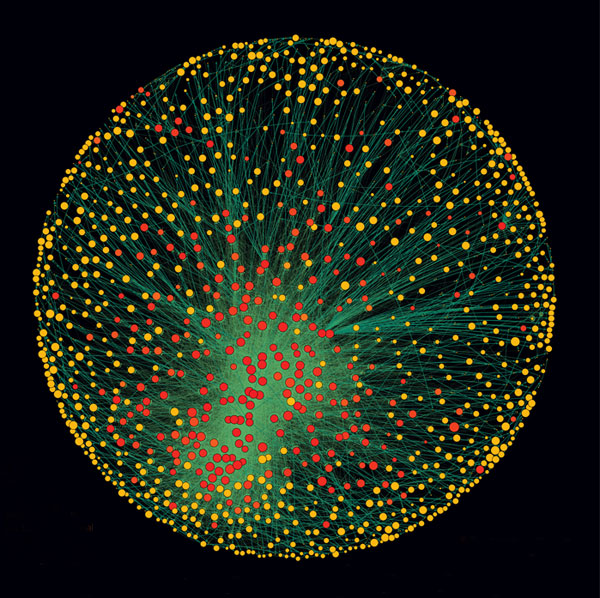

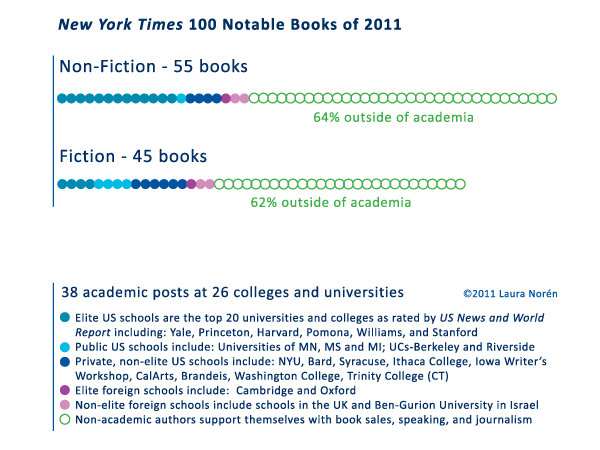

Using the New York Time’s list of 100 Notable books of 2011 that ran over the weekend as part of their Holiday Gift Guide, I created the graph above. As an almost-academic, I am interested in the scope of academic work and found it interesting that less than half of the notable books were written by people with academic affiliations. Michael Burawoy and Craig Calhoun have both called for new roles for scholarship and the university, emphasizing that an academy unhitched from the public sphere is not a viable model and might very well be considered irresponsible, given the scale and scope of social, scientific, and technological challenges facing the globe right now and for the foreseeable future.

So what does it mean that non-academics are writing more of the notable books than are academics?

I cannot answer that question definitively, but I can offer three possible avenues for exploration. First, it could be that academics are irresponsible or lazy and that they have either failed to write well or to address relevant topics. They are off publishing pedantic articles in academic journals that nobody reads to fill out their CVs. This scenario is grave. There is an element of truth to it.

An alternative explanation would be that, in part because this is a *gift* suggestion list, these books are not necessarily the most important, but they are the most well written. If that is the case, then the fact that so many non-academic voices make the list indicate that writing itself is an art, one that is spread much more judiciously across the American populous than are academic positions. It also suggests that thinking clearly and writing well are going on in all sorts of places, not just the ivory tower. This is encouraging. There is an element of truth to it.

A third version of this story begins where the second one left off and suggests that, in fact, if academic books do appear on holiday gift lists of notable books, those academics are shirking their duties as academics. Any book with broad public appeal probably is NOT doing much to advance a field. It’s probably just regurgitating existing research in a kind of “Research Thought X for dummies” kind of way. [Many of the people who adhere to this line of thinking have deep and abiding negative thoughts about Malcolm Gladwell.] The view from this perspective argues that asking academics to be responsible to public audiences is akin to asking people to text and drive. It’s dangerous. It takes one’s eye off the critically important field of action and reorients it, likely towards one’s own navel. The primary activity – analytical research and publishing – will suffer, perhaps taking down innocent bystanders along the way. This is a fairly rigid understanding of the best practice for academic research. There is an element of truth to it.

I invite debate on the points I mentioned and those that I have overlooked in the comments.

What needs work

This graphic is not as elegant as I would like. There are far too many words.

I am fascinated with the nitty gritty details of the schools at which those with academic appointments are working. Including the names of so many schools made the endnotes lengthy. I am of two minds on that. Like I said, I enjoy knowing the details, especially when it comes to fleshing out a category like “Elite.” It’s important to know just how eliteness has been defined. In this case, I used US News and World Report. With respect to most of the schools – Princeton, Harvard, Yale, Oxford, Cambridge, Columbia – I think there is widespread agreement that these schools are at the top of the academic heap and have been for a while. Some might quibble about Pomona and Williams.

The point I was trying to illustrate was that those in academia who have books on the notables list could be seen to be public intellectuals or at least they are doing better at making their work accessible to the public than their colleagues who never make it to such lists. It is especially important that the professors in elite institutions make their work accessible because, unlike their colleagues at public schools or less exclusive private schools, the metaphor about the ivory tower as a mechanism of separation is apt. Very few of us have access to elite institutions. Some have argued that those in academia have some responsibility for making their work accessible to broader publics.

References

Burawoy, Michael. (2005 [2004]) http://ccfi.educ.ubc.ca/Courses_Reading_Materials/ccfi502/Burawoy.pdf [Presidential Keynote Address at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association] American Sociological Review Vol. 70.

Calhoun, Craig. (2006) “Social Science for Public Knowledge”>The University and the Public GoodThesis Eleven Vol. 84(7).

New York Times, Sunday Magazine. (November 2011) “100 Notable Books of 2011” [Holiday Gift Guide]