What works

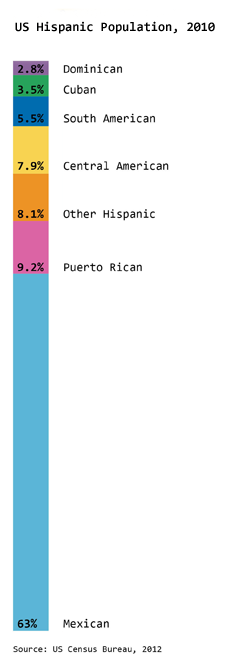

The Hispanic population is the fastest growing minority ethnic group in America. In the previous post about Race and Ethnicity in America, I showed the overall racial and ethnic proportions in America (2010 data). The graphic here specifically looks at what we mean when we say Hispanic in America. The predominant country of origin for Hispanic Americans is Mexico, accounting for almost two-thirds of the Hispanic population (63%). The Mexican American population continues to grow; Mexico is a much more populous place than, say, Puerto Rico, Cuba, or the Dominican Republic which is one explanation for the disparity in locations of origin. However, because Puerto Rico is part of the United States, it is the next largest source of Hispanic Americans at 9.2% followed closely by Hispanics from Central American countries at 7.9%.

What needs work

Admittedly, the graphic is nothing special just a stacked bar. I’m sharing it because it seemed miserly of me withhold it since it offers a better understanding of the ethnic make-up of America than the previous graphic alone. I probably should have posted it in the previous post, but it’s too late for that now.

References

Ennis, Sharon, Merarys Rios-Varga, and Nora Albert. 2011. The Hispanic Population. Census Briefs 2010. US Census Bureau.