What works

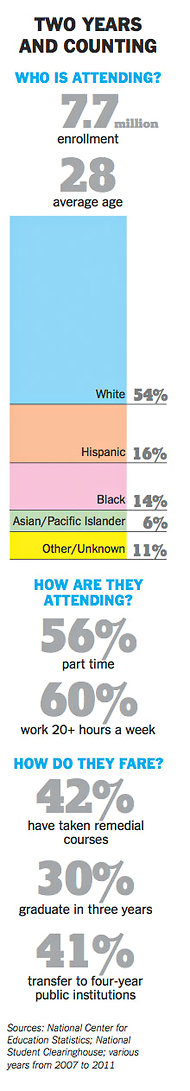

What I like about the graphic is that it provides a quick demographic snapshot of the community college population so that readers of the adjacent article have an additional piece of context as they try to absorb what it is that is new about The New Community College at CUNY” program. Graphics like this one make for dry written copy, but they add an important element of depth and context to news articles. News articles are always trying to find what is new which can make it challenging for journalists to slip demographics into their stories. Demographics are usually fairly slow-to-change and almost never make the news. Occasionally, there are stories about the crossing of particular tipping points (see any mention of <a href="http://www.theatlanticcities.com/neighborhoods/2012/05/us-metros-are-ground-zero-majority-minority-populations/2043/"majority-minority cities, states, and other places). But typically, demographics alone are not new enough to be newsworthy even though demographic information is salient for the critical analysis of many programs and social issues.

Community colleges in Obama’s plan for a better economic situation

This graphic ran in a long article about a new community college program at the City University of New York in which students will be required to take a strictly defined course in which remedial education is integrated into syllabi and will receive close, frequent mentoring. The number of stories about the social, educational, and financial situation facing community colleges in the US has increased over the past 6-12 months, thanks in part to efforts by Obama’s administration. In February the White House Press office announced a program to train 2 million workers by relying on the community college system that followed the 2010 announcement of the “Skills for America’s Future” community college-employer partnership program, a joint effort with the Aspen Institute.

Dr. Jill Biden, Joe Biden’s wife, worked in community colleges for 18 years and it is nice to see that her expertise is not being overlooked.

What needs work

After that lengthy praise for the inclusion of demographics above, I have many points of improvement.

First, demographic information is snapshot information. It’s taken at one point in time of what, in this case, is only part of the population. What I would have done, two options:

1+st option: compare community college demographics now to community college demographics of the past. Is the current enrollment pattern stable? Is it changing in important ways? This will help readers figure out whether the new program the article mentions is addressing change well.

+ 2nd option (my favored option): compare the community college population to the high school population and to the 4-year college population. The article is about the design of educational institutions so let’s see how community college enrollments compare to their nearest brethren.

Second, the graphic is off to a great start but doesn’t include enough demographic data. From the Aspen Institute’s website (which used data from the American Association of Community Colleges), I gathered up this additional demographic information.

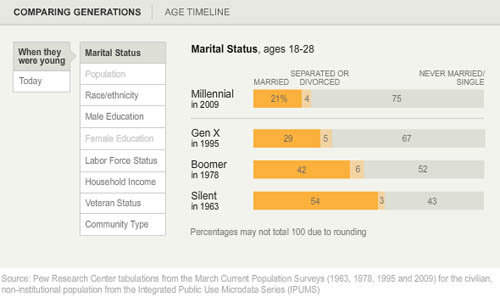

As of 2007–2008 (American Association of Community Colleges)

- Average age of community college students: 28

- Median age of community college students: 23

- 21 or younger: 39%

- 22-39: 45%

- 40 or older: 15%

- First generation to attend college: 42%

- Single parents: 13%

- Non- US Citizens: 6%

- Veterans: 3%

- Students with disabilities: 12%

As of fall 2008

- Women: 58%

- Men: 42%

- Minorities: 45%

For the age data, I would have graphed it so that we could see that even though the median age is relatively high, it’s pulled that way by a long tail to the right.

Further, the Aspen Institute page got into a bit more detail on the way students with remedial needs fare in the community college system.

The percentage of community college students who must take one or more remedial courses is estimated at about 80%. Fewer than 25% of community college students who took a remedial education course completed a degree within 8 years of enrollment. (Community College Resource Center)

We can compare the 80% who reportedly need remedial courses to the 42% who have taken them as well as the fact that actually taking time out to get the remedial coursework seems to slow progress to graduation to understand why the CUNY program integrated remedial work into existing courses.

The final piece of information that the Aspen Institute included in their overview that wasn’t in the NYTimes graphic is not demographic data, but it is still important for many of the same reasons that demographic data are relevant.

Revenue Sources for Community Colleges (American Association of Community Colleges)

- State funds 36%

- Local funds 19%

- Tuition and fees 16%

- Federal funds 14%

- Other: 15%

In both cases, the information is presented in a basic list format. Not all that visually stimulating. I like the Aspen Institute’s lists better because they do not privilege numbers by making them huge compared to the text. While it would have been possible to do more with graphics in both cases, I would rather have the information included and spare than excluded because it fails to meet designerly criteria.

References

Pérez-Peña, Richard. (20 July 2012) The New Community College Try. The New York Times, Education Life section.

The White House. (13 February 2012) FACT SHEET: A Blueprint to Train Two Million Workers for High-Demand Industries through a Community College to Career Fund. Office of the Press Secretary.