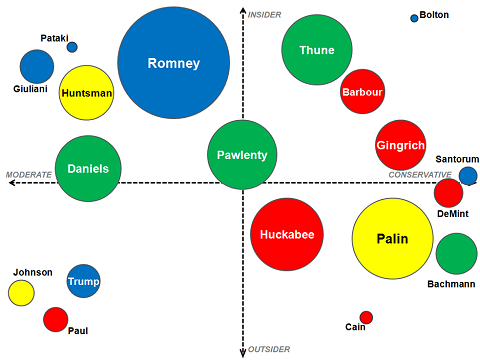

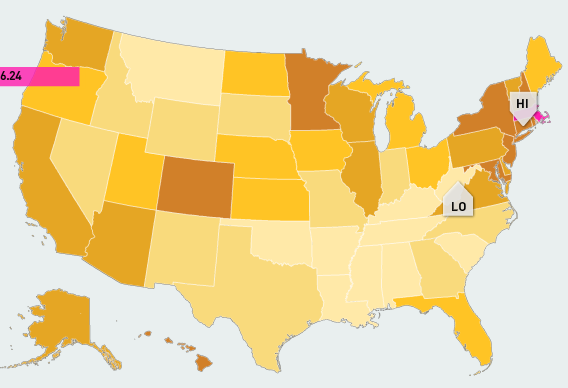

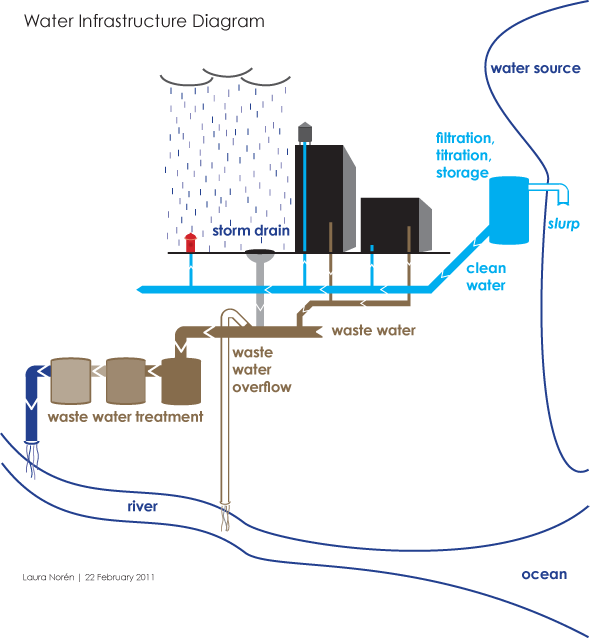

Water Infrastructure Schematic Diagram*

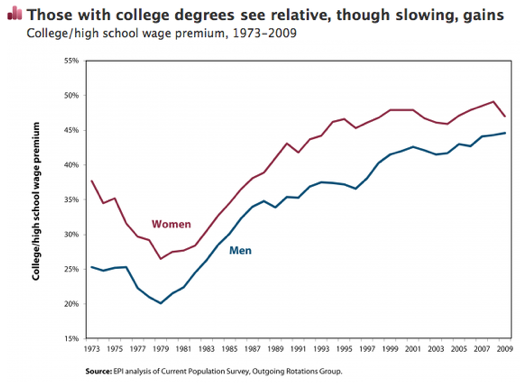

I put together the diagram above to help me explain how water is delivered and taken away from urban locations. The point I want to make with the diagram is that the infrastructure is designed to deliver water to ‘typical’ buildings and that this means people who are wandering around cities where buildings are all private also lack access to water. There is a political debate going on right now about whether or not access to water is a human right – the UN voted on this and decided water IS a human right but large countries like the US disagreed. When the US does not back UN resolutions, those UN resolutions tend not to mean as much.

So why would the US vote against this resolution? I am not altogether sure, but I believe it has something to do with the fact that many places have privatized their water. Privatization of water takes different faces. Sometimes a system like the one diagrammed above is privatized. Studies have shown that when this happens, the company that sets up a system like the one above delivers a poorer quality product – more sedimentation and other low level contaminants which are the typical results of choosing sources quite close to cities. The closer the source is to the delivery, the lower the expenditure for engineering and installation of water mains, monitoring stations along the route, and reservoirs. The other way in which water can be privatized is through bottling – bottled water in some parts of Africa is more expensive than Coca-Cola. And this in areas that may have no access to safe alternatives for drinking water. Nestle owns the Poland Springs brand and folks in Maine are scrambling to get hydrological studies performed that can prove Nestle’s water extractions are drawing down lake volumes on adjacent properties. The only way to fight Nestle, it seems, is to prove that they are damaging one’s own property and yet water sources – rivers, lakes, oceans, springs – technically do not belong to private individuals. The individuals or corporations can own the land surrounding them, but the water is a bit like air and cannot be owned. (Rights to the fish found in the water CAN be owned. As you can see this gets complicated quickly.)

The diagram above contains none of the politics of the discussion below. For me, it is important to attempt to create graphics that are not political, even when I am creating them for the express purpose of delivering a presentation that takes a side in a political fight. For me, the challenge is two-fold. First, I face the technical difficulty of creating any kind of complex diagram. I’ll leave questions about execution out of this particular discussion though feel free to comment on execution below. Second, when I know I have a political message that I want to keep out of my graphics, I am often too far into my own head to be able to step back and determine whether I have created something that is both comprehensive enough to tell a complete (but apolitical) story and one that does not drift into the political. As it is, this diagram seems to err on the side of being incomplete rather than being more fully detailed where the details start to carry politics with them. My larger point is that this is one way in which cities are exclusionary zones by design. It would be easy to find a way to provide the basic infrastructure to supply water outside of buildings – fire hydrants do just that. But maintaining the ‘last mile’ of infrastructure is almost always completely given over to the private sector. Individuals and companies maintain bathrooms with all of their fixtures, cleaning, and maintenance requirements. This is big business. Just about every shop and restaurant on the street in New York reserves the rights to the bathroom for customers only.

One of Starbucks redeeming qualities is that their bathrooms tend to be open to all, proving that it is possible to continue to service a relatively affluent clientele no matter who is in the bathroom.

Obama on Water

The word on the political street is that even though Obama’s stimulus efforts contain plans to address infrastructure, water infrastructure has been taken off the table at this point. Our water infrastructure is ageing; most of the current infrastructure is due to age out of acceptable functionality in the next ten years. Already there are an average of 240,000 water main breaks. Just yesterday the New York Times reported that a dam outside of Bakersfield is uncomfortably close to catastrophic failure, threatening the lives and livelihoods of thousands of people. There are another 4400 dams in the US that require work in order to fall within comfortable safety ranges. Some are publicly owned, some are privately owned. In either case, it is unclear which entities can foot the bill (projected at $16 billion dollars over 12 years).

*This diagram uses New York City as a guide. Not all cities have overflow valves that risk the release of raw sewage due to increases in rain. What’s more, in New York there are some other systems in place to recapture some of the overflow at the point of release. But this is a different kind of political discussion, one that focuses on the other typical focus of water discussions – the environment.

References

Ascher, Kate. (2005) The Works: Anatomy of a City. New York: The Penguin Press.

Bone, Kevin, ed. and Gina Pollara, Associate Ed. (2006) Water-Works: The architecture and engineering of the New York City water Supply. The Cooper Union School of Architecture, New York: The Monacelli Press.

Bozzo, Sam. (2009) Blue Gold: World Water Wars [Documentary film, available streaming for free]

Davis, Mike. (2006) Planet of Slums. Brooklyn, NY: Verso Books.

Fountain, Henry. (2011) Danger Pent Up Behind Aging Dams. New York Times. 21 February 2011.