How is the scoring system determined?

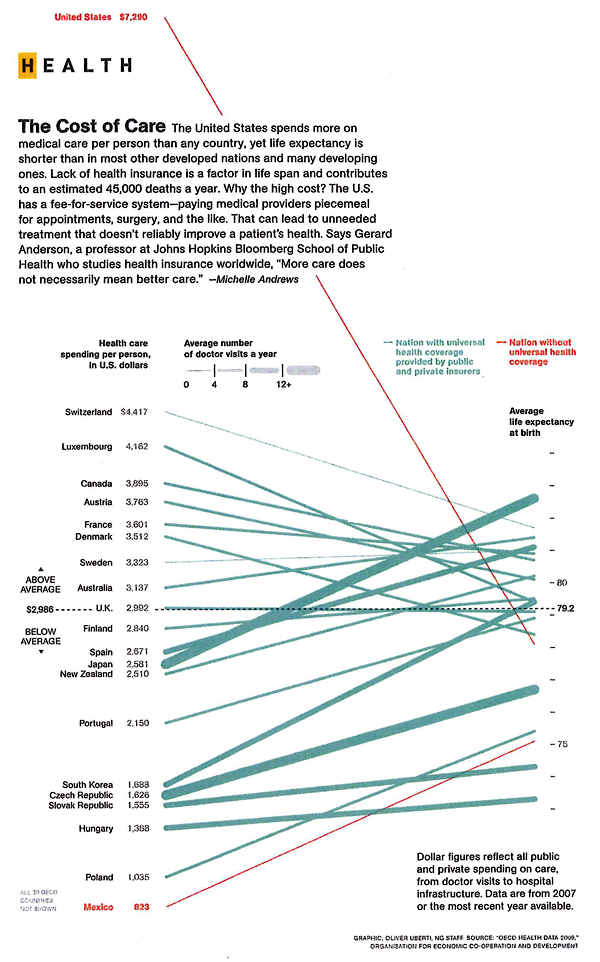

British researchers affiliated with the Independent Scientific Committee on Drugs met for a one day workshop and constructed a composite scoring system to determine which drugs are most harmful both to individuals and to society collectively. Scores can range from 0 – 100. Authors David Nutt, Leslie King and Lawrence Phillips found that,

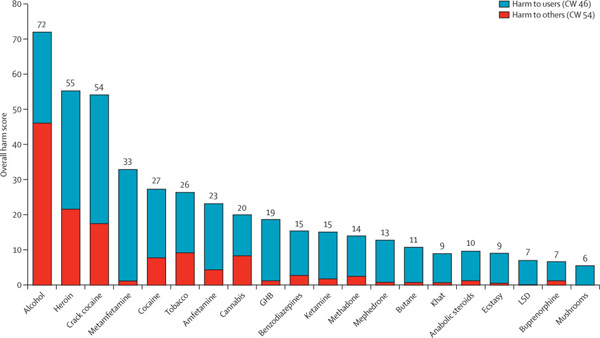

heroin, crack cocaine, and metamfetamine were the most harmful drugs to individuals (part scores 34, 37, and 32, respectively), whereas alcohol, heroin, and crack cocaine were the most harmful to others (46, 21, and 17, respectively). Overall, alcohol was the most harmful drug (overall harm score 72), with heroin (55) and crack cocaine (54) in second and third places.

The full list of factors that were included in the composite score are here:

- Mortality

- Damage

- Dependence

- Impairment of mental functioning

- Loss of tangibles

- Loss of relationships

- Injuries to others

- Crime increase

- Environmental degradation

- Family breakdowns

- International turmoil

- Economic cost

- Loss of community cohesion and reputation

Though it is possible to go into an explanation of how each of these was measured and subsequently combined to produce the composite scores, I am going to leave that discussion to the authors of the original study. There’s an overview graph below and the full article Drug Harms in the UK: A multi-criteria decision analysis is at the Lancet.

What can be done?

I found it interesting that there was no attempt made to distinguish between legal and illegal drugs. Yes, of course, some drugs are not clearly legal or illegal. They are legal when prescribed and supervised by a doctor but illegal when used off-label or outside the medical authority system (like anabolic steroids, methadone, and marijuana in California). I assumed that most methadone users are under some kind of supervision but that most anabolic steroid users are using the steroids off-label (ie illegally). You can quibble with my choices below. The point here is that I found the graph to have more context if the legality issue was visually inscribed into it.

There are age limits and places where it’s illegal to smoke or drink, but for the most part everyone will be able to use alcohol and tobacco legally for most of their lives. Methadone is probably being used legally in most cases. That’s why I shaded those bars grey. I am not expert on methadone, but I see that it is much less harmful to users and to society than heroin, the drug it stands in for, so I guess if this were the only data I had to make a decision about continuing methadone treatment programs, I would keep them going. I would also call for close scrutiny of methadone programs. Something is clearly not working as well as it could be.

As for alcohol and tobacco…well…it’s hard to argue *for* the continuing legality of alcohol. How large do detriments to society have to be to trigger additional control mechanisms? The authors of the study noted that alcohol is part of society and it isn’t going anywhere. I agree. Prohibition was a failed experiment in this country and I’m not suggested we try it again. However, I would like to reopen the debate about how the negative impacts of alcohol can be alleviated. I recommend that all new cars must have breathalyzers in them. If the driver cannot blow a legal sample, the car won’t start. Yes, people could game that system by having their friends blow for them, but often one’s friends are also drunk. And hopefully, friends really wouldn’t let their friends drive drunk. Once upon a time, seatbelts were considered extraneous and seatbelt laws were considered constraints upon American’s rights to freedom and the pursuit of happiness. Well, when a drunk driver kills one of your family members, you might decide that the sudden loss of your mother or son or niece puts a much bigger crimp in your pursuit of happiness than a breathalyzer in your car ever would have. Will breathalyzers make cars cost more? Probably. But the cost of dealing with car accidents caused by drunken driving, even when they aren’t fatal, is absorbed by random individuals who happened to be in the wrong place/time as well as tax payers who pay to repair guard rails, subsidize public hospitals and EMTs, pay cops’ salaries, and so on.

References

Nutt, David J, Leslie A King, and Lawrence D Phillips. (6 November 2010) “Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis” The Lancet, Vol 376(9752): 1558 – 1565.