USA Today Flash Animated Graphic accompanying the headline “Deaths Down on America’s Roads”

What Works

Nothing is working here and I’m not just saying that because it’s flash and I can’t repost it. Please link through for a hot minute and look at it anyways.

What Needs Work

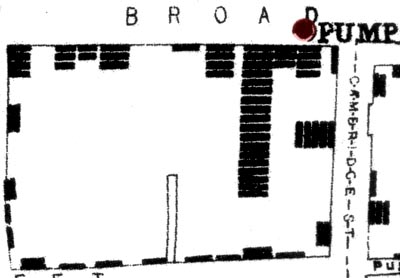

My problem with this graphic is that it is ONLY a map of the US, except for the few seconds when you roll your mouse over it. Even then, you don’t end up seeing a pattern, you just see little pop up windows with some numbers in them. Information graphics need to artfully, intelligently, dare I say cleverly weave the information into the graphic so that the two become greater than the sum of their parts. None of that happens here.

The map of the US is still just a map of the US. No shading, no numbers, no way to tell that we’re talking about traffic deaths. Even just mapping out the interstate highway system would have given a hint of a visual clue to tell us what we’re talking about. In the previous post, Snow stacked bars to indicate dead bodies. Maybe it’s a little over the top, but if we are addressing the notion of a change in body count, I would like to see some visual representation either of bodies or of change (change is more abstract and probably more appropriate for USA Today than a visual representation of a body count). Furthermore, I want to know if there really is a relationship between gas prices and body counts which *could* be explored looking across states. States tax gas at different rates resulting in variations from one state to the next. Sensitively factor in income and unemployment and we might be able to get a sense of how much gas prices impact mortality on the roads. Even more interesting would be whether it’s the fact that people aren’t on the road at all that prevents them from dying out there (no gas = no go) or if it is somewhat more subtle – perhaps people drive slower to be more fuel efficient rather than staying home and it is the slow down, not the no-go that keeps people alive. The more likely scenario would also point out that cars continue to get safer and that seatbelt laws work. If we could look at the data over time, we’d have a better idea how more quickly traffic fatalities dropped in 2008 than in other recent years, which would help factor in the cars-are-safer-now + more-states-have-seatbelt-laws effects.

This graphic falls woefully short of even hinting at any of these questions. I wish they had left it out altogether, forcing everyone to read the article in full.