What works

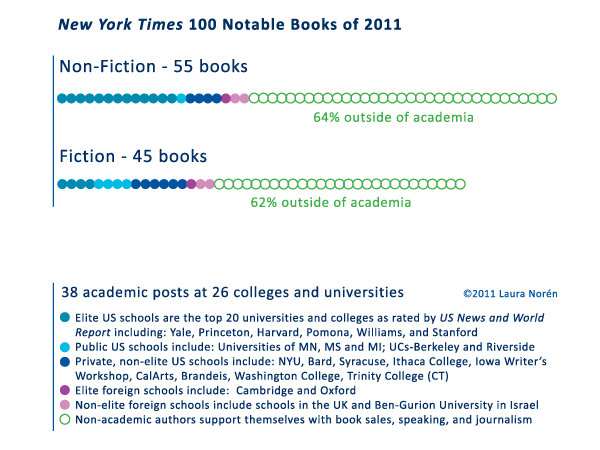

Using the New York Time’s list of 100 Notable books of 2011 that ran over the weekend as part of their Holiday Gift Guide, I created the graph above. As an almost-academic, I am interested in the scope of academic work and found it interesting that less than half of the notable books were written by people with academic affiliations. Michael Burawoy and Craig Calhoun have both called for new roles for scholarship and the university, emphasizing that an academy unhitched from the public sphere is not a viable model and might very well be considered irresponsible, given the scale and scope of social, scientific, and technological challenges facing the globe right now and for the foreseeable future.

So what does it mean that non-academics are writing more of the notable books than are academics?

I cannot answer that question definitively, but I can offer three possible avenues for exploration. First, it could be that academics are irresponsible or lazy and that they have either failed to write well or to address relevant topics. They are off publishing pedantic articles in academic journals that nobody reads to fill out their CVs. This scenario is grave. There is an element of truth to it.

An alternative explanation would be that, in part because this is a *gift* suggestion list, these books are not necessarily the most important, but they are the most well written. If that is the case, then the fact that so many non-academic voices make the list indicate that writing itself is an art, one that is spread much more judiciously across the American populous than are academic positions. It also suggests that thinking clearly and writing well are going on in all sorts of places, not just the ivory tower. This is encouraging. There is an element of truth to it.

A third version of this story begins where the second one left off and suggests that, in fact, if academic books do appear on holiday gift lists of notable books, those academics are shirking their duties as academics. Any book with broad public appeal probably is NOT doing much to advance a field. It’s probably just regurgitating existing research in a kind of “Research Thought X for dummies” kind of way. [Many of the people who adhere to this line of thinking have deep and abiding negative thoughts about Malcolm Gladwell.] The view from this perspective argues that asking academics to be responsible to public audiences is akin to asking people to text and drive. It’s dangerous. It takes one’s eye off the critically important field of action and reorients it, likely towards one’s own navel. The primary activity – analytical research and publishing – will suffer, perhaps taking down innocent bystanders along the way. This is a fairly rigid understanding of the best practice for academic research. There is an element of truth to it.

I invite debate on the points I mentioned and those that I have overlooked in the comments.

What needs work

This graphic is not as elegant as I would like. There are far too many words.

I am fascinated with the nitty gritty details of the schools at which those with academic appointments are working. Including the names of so many schools made the endnotes lengthy. I am of two minds on that. Like I said, I enjoy knowing the details, especially when it comes to fleshing out a category like “Elite.” It’s important to know just how eliteness has been defined. In this case, I used US News and World Report. With respect to most of the schools – Princeton, Harvard, Yale, Oxford, Cambridge, Columbia – I think there is widespread agreement that these schools are at the top of the academic heap and have been for a while. Some might quibble about Pomona and Williams.

The point I was trying to illustrate was that those in academia who have books on the notables list could be seen to be public intellectuals or at least they are doing better at making their work accessible to the public than their colleagues who never make it to such lists. It is especially important that the professors in elite institutions make their work accessible because, unlike their colleagues at public schools or less exclusive private schools, the metaphor about the ivory tower as a mechanism of separation is apt. Very few of us have access to elite institutions. Some have argued that those in academia have some responsibility for making their work accessible to broader publics.

References

Burawoy, Michael. (2005 [2004]) http://ccfi.educ.ubc.ca/Courses_Reading_Materials/ccfi502/Burawoy.pdf [Presidential Keynote Address at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association] American Sociological Review Vol. 70.

Calhoun, Craig. (2006) “Social Science for Public Knowledge”>The University and the Public GoodThesis Eleven Vol. 84(7).

New York Times, Sunday Magazine. (November 2011) “100 Notable Books of 2011” [Holiday Gift Guide]

Comments 11

C.W. Anderson — November 28, 2011

I think a far more interesting metric would be if the academic authors are tenured, or not. Most often, writing "accessible" books is seen as something professors do once they have tenure and are thus "allowed" to be public intellectuals.

Chris H. — November 28, 2011

I think the value in this list of books comes from it's simple explanations of concepts that people may or may not know. If the mixture of writing and old academic concepts (new to reader) introduces them to the field of interest, then I believe that it could be very helpful.

That's just me. What does anyone else think?

Siva Vaidhyanathan — November 28, 2011

Just because the Times says something is "notable" does not mean that it is or that a book the Times failed to notice is not. The Times has a policy of favoring trade books with large advances that academics are not eligible for. Beside that, I think academics scored quite respectably on your scale. I would have guessed the number to be about 10 percent.

8 Bring Art Sites :: Gaia Gallery — November 28, 2011

[...] Featured in The New York Times Book ReviewThe New York Times’ Hypocrisy on Tax LoopholesNew York Times 100 notable books var [...]

Peter Dimock — December 3, 2011

Maybe what matters most in all this is the way the public sphere and the circulation of words in various formats with various degrees of communicative autonomy, with various degrees and kinds of authority, and according to various business models with various profit margins are all being mutually reconfigured in lots of volatile ways simultaneously. This is a wonderful graph because it suggests that we can actually make maps of these reconfigurations with which to try to locate ourselves and each other. Thank you!

Peter Dimock

Arturo — December 6, 2011

Interesting post!--somebody forwarded this to me because last year I co-authored a piece in contexts examining the best selling sociology books out there.

http://contexts.org/articles/spring-2010/a-fresh-look-at-sociology-bestsellers/

I'm afraid our estimates were a bit starker than yours...excluding psychologists, economists and historians (that all far out-sell sociologists) we found that sociologists accounted for less than 5% of the top 1K titles that pass as social science in the last five year...journalists, and private writers, sell around 90% of the books related to race, poverty, crime, gender, globalization, technology and inequality than social scientists (at least to the data we obtained from Nielsons)...we played this down in the article and focused on the 37 or so titles that did relatively well...it seemed like titles that brought on a strong narrative voice like "gang leader for the day" and dealt with issues of race, poverty and crime (like Glassner's "Culture of Fear") did relatively better than other titles written by PhDs

Arturo — December 6, 2011

Some of O'Reilly's books were actually categorized as social science in the sales data, so funny you mention him. He came up as a big player in the genre, as well obama. The #1 book was germs, guns and steel by J. Diamond, so yea, there's a bit of unclear parameters in the industry about what qualifies as social science...

but still, it was shocking to me how many books there were out there related to the domain of social science (race, immigration, poverty, globalization etc.) that sell relatively well compared to O'Reilly's books but are not written by academics....i'm not sure to what extent it's our writing or the style of presenting data/information, that works against public attention of sociology in particular....I did notice reading some of the titles, that journalists often cite sociologists, so maybe we're just not good at packaging ourselves....i don't know for sure, I guess it's an empirical question as they say

People Can’t Tell the Difference Between a Men’s Mag and a Rapist…And More Stories « Welcome to the Doctor's Office — December 13, 2011

[...] New York Times 100 notable books | Who reads academic authors? [...]