Information graphics and Illustrations

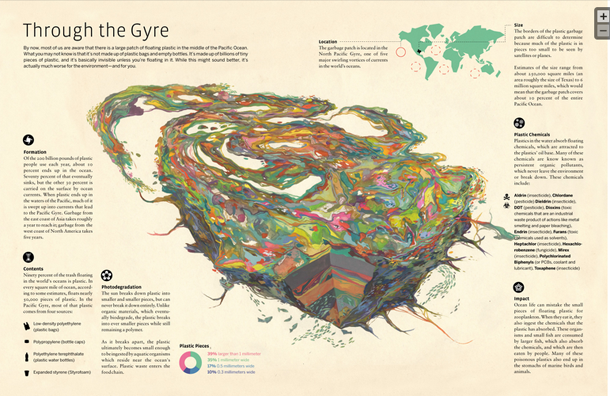

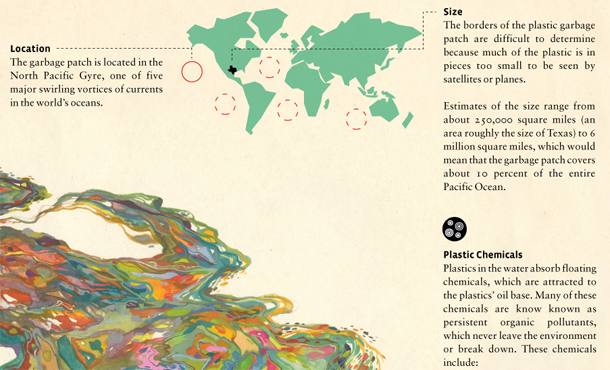

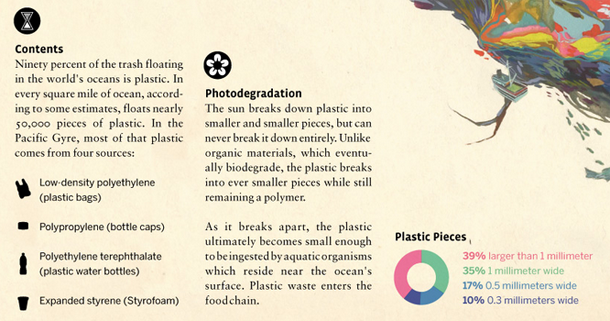

Information graphics generally do not include significant elements of illustration. It is even more rare that they are dominated by illustrations the way “Through the Gyre” is. Jacob McGraw-Mickelson created the illustration – it’s his imagination of what the Pacific Gyre might be like, not an anatomical cross-section. Using an illustration in a place where we come to expect something schematic and, therefore, representative of reality could be a dangerous play-on-truth using images and conventional expectations to convince viewers of a truth they will never be able to confirm. The Pacific Gyre is nearly impossible to visualize because it is operating at competing scales. The pieces of plastic are teeny tiny but they cover a swath of ocean that’s about as big as Texas. Reports of its density at various depths are still being developed.

Because the gyre is so difficult to visualize McGraw-Mickelson’s illustration of it has an easy time standing in for reality. We have no other photographs or scientific diagrams (yet) that aim to give us a visual overview. The ease of convincing a viewership could be seen as a kind of deceit-with-images but I prefer to think of it as art in the service of environmentalism. It may not be ‘representative’ of reality or even provide a schematic for thinking through oceanographic relationships. But it does bring gravity and depth to the following factoids that were developed as more traditional information graphics around the main illustration of the gyre.

What Works

This graphic gave me a whole new way to think through problems related to representing important concepts and ideas that do not have clear schematics, photos, or graphics but can inspire deep reflection. I bought a copy of the print of just the ‘gyre’ to remind myself to be cautious about my embrace of the American lifestyle. I could end up eating that plastic bag again someday as it makes it way into the food cycle.

References

McGraw-Mickelson, Jacob. (2009) “Through the Gyre” [illustration] featured in 2009’s best information graphics at GOOD Transparency blog