Our Pointlessly Gendered Products Pinterest board is funny, no doubt. When people make male and female versions of things like eggs, dog shampoo, and pickles, you can’t help but laugh. But, of course, not it’s not just funny. Here are five reasons why.

Our Pointlessly Gendered Products Pinterest board is funny, no doubt. When people make male and female versions of things like eggs, dog shampoo, and pickles, you can’t help but laugh. But, of course, not it’s not just funny. Here are five reasons why.

1. Pointlessly gendered products affirm the gender binary.

Generally speaking, men and women today live extraordinarily similar lives. We grow up together, go to the same schools, and have the same jobs. Outside of dating — for some of us — and making babies, gender really isn’t that important in our real, actual, daily lives.

These products are a backlash against this idea, reminding us constantly that gender is important, that it really, really matters if you’re male and female when, in fact, that’s rarely the case.

But if there were no gender difference, there couldn’t be gender inequality; one group can’t be widely believed to be superior to the other unless there’s an Other. Hence, #1 is important for #3.

Affirming the gender binary also makes everyone who doesn’t fit into it invisible or problematic. This is, essentially, all of us. Obviously it’s a big problem for people who don’t identify as male or female or for those whose bodies don’t conform to their identity, but it’s a problem for the rest of us, too. Almost every single one of us takes significant steps every day to try to fit into this binary: what we eat, whether and how we exercise, what we wear, what we put on our faces, how we move and talk. All these things are gendered and when we do them in gendered ways we are forcing ourselves to conform to the binary.

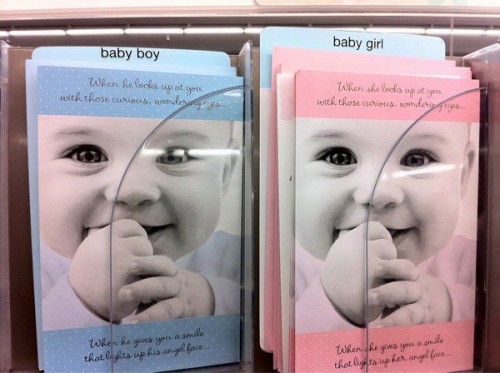

2. Pointlessly gendered products reinforce stereotypes.

Pointlessly gendering products isn’t just about splitting us into two groups, it’s also about telling us what it means to be in one of those boxes. Each of these products is an opportunity to remind us.

3. Pointlessly gendered products tell us explicitly that women should be subordinate to or dependent on men.

All too often, gender stereotypes are not just about difference, they’re about inequality. The products below don’t just affirm a gender binary and fill it with nonsense, they tell us in no uncertain terms that women and men are expected to play unequal roles in our society.

Girls are nurses, men are doctors:

Girls are princesses, men are kings:

4. Pointlessly gendered products cost women money.

Sometimes the masculine and feminine version of a product are not priced the same. When that happens, the one for women is usually the more expensive one. If women aren’t paying attention — or if it matters to them to have the “right” product — they end up shelling out more money. Studies by the state of California, the University of Central Florida, and Consumer Reports all find that women pay more. In California, women spent the equivalent of $2,044 more a year (the study was done in 1996, so I used an inflation calculator).

This isn’t just something to get mad about. This is real money. It’s feeding your kids, tuition at a community college, or a really nice vacation. When women are charged more it harms our ability to support ourselves or lowers our quality of life.

5. Pointlessly gendered products are stupid. There are better ways to deliver what people really need.

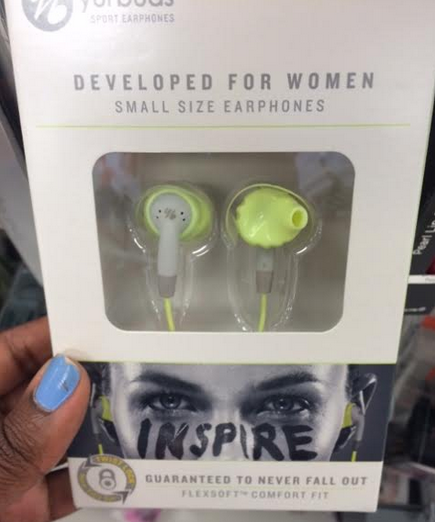

One of the most common excuses for such products is that men and women are different, but most of the time they’re using gender as a measure of some other variable. In practice, it would be smarter and more efficient to just use the variable itself.

For example, many pointlessly gendered products advertise that the one for women is smaller and, thus, a better fit for women. The packaging on these ear buds, sent in by LaRonda M., makes this argument.

Maybe some women would appreciate smaller earbuds, but it would still be much more straightforward to make ear buds in different sizes and let the user decide which one they wanted to use.

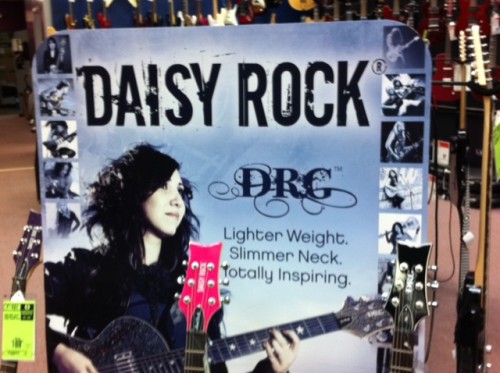

Products like these make smaller men and larger women invisible. They also potentially make them feel bad or constrain their choices. When the imperative for women is to be small and dainty, how do women who don’t use smaller earbuds feel? Or, maybe the small guy who wants to learn how to play guitar never will because men’s guitars don’t fit him and he won’t be caught dead playing this:

In sum, pointlessly gendered products aren’t just a gag. They’re a ubiquitous and aggressive ideological force, shaping how we think, what we do, and how much money we have. Let’s keep laughing, but let’s not forget that it’s serious business, too.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

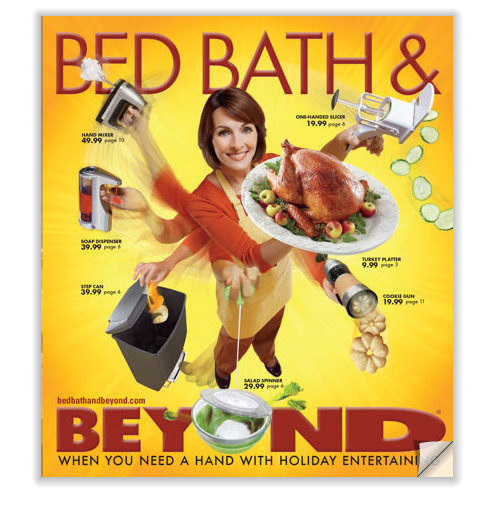

Alone with the responsibility of making a holiday for everyone else, the woman manages to mobilize technology and goods from BB&B to make it happen. Ironically, the text reads: “When you need a hand with holiday entertaining,” but actual human help in the form of hands is absent. Apparently it’s easier for women to grow five extra arms than it is to get kids and adult men to pitch in.

Alone with the responsibility of making a holiday for everyone else, the woman manages to mobilize technology and goods from BB&B to make it happen. Ironically, the text reads: “When you need a hand with holiday entertaining,” but actual human help in the form of hands is absent. Apparently it’s easier for women to grow five extra arms than it is to get kids and adult men to pitch in.