I’ve been reluctant to write about the terrible events at Sandy Hook Elementary School because the wounds are still too fresh for any kind of dispassionate analysis. As a social scientist, however, I’m disappointed by the fear-mongering and selective presentations of the research evidence I’ve read in reports and op-eds about Friday’s awful killing.

Such events could help move us toward constructive actions that will result in a safer and more just world — or they could push us toward counter-productive and costly actions that simply respond to the particulars of the last horrific event. I will make the case that a narrow focus on stopping mass shootings is less likely to produce beneficial changes than a broader-based effort to reduce homicide and other violence. We can and should take steps to prevent mass shootings, of course, but these rare and terrible crimes are like rare and terrible diseases — and a strategy to address them is best considered within the context of more common and deadlier threats to population health. Five points:

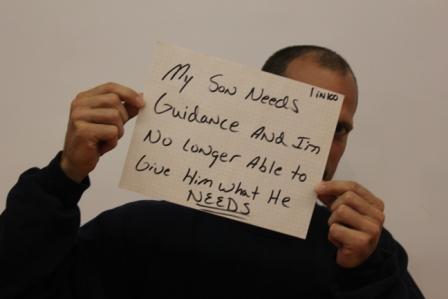

1. The focus on mass shootings obscures over 99 percent of homicide victims and offenders in the United States. The numbers should not matter to parents who must bury their children, but they are important if policy makers are truly committed to reducing violent deaths. There are typically about 25 mass shootings and 100 victims each year in the United States (and, despite headlines to the contrary, mass shootings have not increased over the past twenty years). These are high numbers by international standards, but they pale relative to the total number of killings – about 14,612 victims and 14,548 offenders in 2011. In recent years, the mass shooters have represented less than two-tenths of 1 percent of the total offenders, while the victims have represented less than one percent of the total homicide victims in any given year. We are understandably moved by the innocence of the Sandy Hook children, but we should also be moved by scores of other victims who are no less innocent. There were 646 murder victims aged 12 or younger in the United States in 2011 alone — far more than all the adults and children that died as a result of mass shootings.

2. The focus on mass shootings leads to unproductive arguments about whether imposing sensible gun controls would have deterred the undeterrable. As gun advocates are quick to point out, many of the perpetrators in mass shootings had no “disqualifying” history of crime or mental disorder that would have prevented them from obtaining weapons. And, the most highly motivated offenders are often able to secure weapons illegally. Even if such actions do little to stop mass shootings, however, implementing common-sense controls such as “turning off the faucet” on high capacity assault weapons, tightening up background checks, and closely monitoring sales at gun shows are prudent public policy. But the vast majority of firearms used in murders are simple handguns. I would expect the no-brainer controls mentioned above to have a modest but meaningful effect, but we will need to go farther to have anything more than an incremental effect on mass shootings and gun violence more generally.

3. The focus on mass shootings obscures the real progress made in reducing the high rates of violence in the United States. I heard one commentator suggest that America had finally “hit bottom” regarding violence. Well, this is true in a sense — we actually hit bottom twenty years ago. The United States remains a violent nation, but we are far less violent today than we were in the early 1990s. Homicide rates have dropped by 60 percent and the percentage of children annually exposed to violence in their households has fallen by 69 percent since 1993. We can and should do better, of course, but these are not the worst of times.

4. The focus on mass shootings exaggerates the relatively modest correlation between mental illness and violence. Those who plan and execute mass shootings may indeed have severe mental health problems, though it is difficult to say much more with certainty or specificity because of the small number of cases in which a shooter survives to be examined. We do know, however, that the correlation between severe mental illness and more common forms of violence is much lower — and that many types of mental health problems are not associated with violence at all.

5. The focus on mass shootings leads to high-security solutions of questionable efficacy. Any parent who has attempted to drop off a kid’s backpack knows that security measures are well in place in many schools. Rates of school crime continue to fall, such that schools are today among the safest places for children to spend so many of their waking hours. In 2008-2009, for example, only 17 of the 1,579 homicides of youth ages 5-18 occurred when students were at school, on the way to school, or at school-associated events. Of course we want to eliminate any possibility of children being hurt or killed at school, but even a 2 percent reduction in child homicide victimization outside of schools would save more lives than a 90 percent reduction in school-associated child homicide victimization. While every school must plan for terrible disasters in hopes that such plans will never be implemented, outsized investments in security personnel and technology are unlikely to serve our schools or our kids.

In the aftermath of so many deaths I am neither so cynical as to suggest that nothing will change nor so idealistic as to suggest that radical reform is imminent. I’m just hoping that the policy moves we make will address our all-too-common horrors as well as the rare and terrible events of the past week.