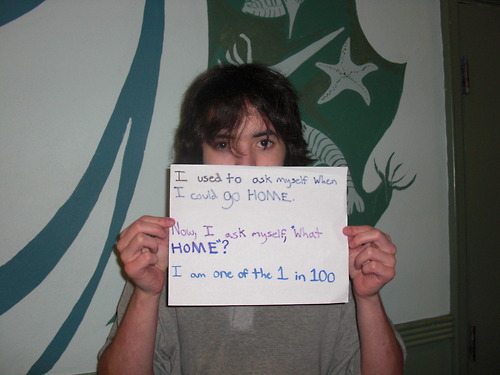

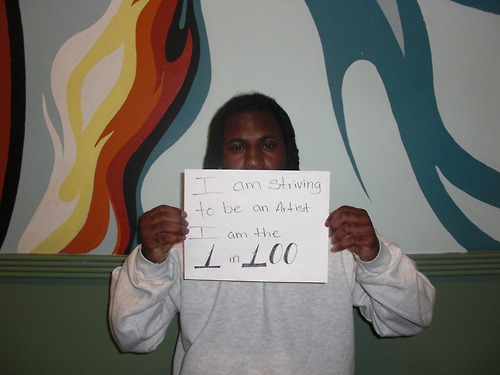

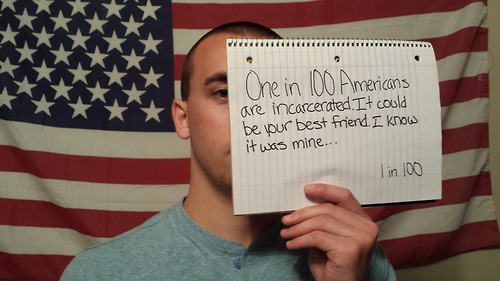

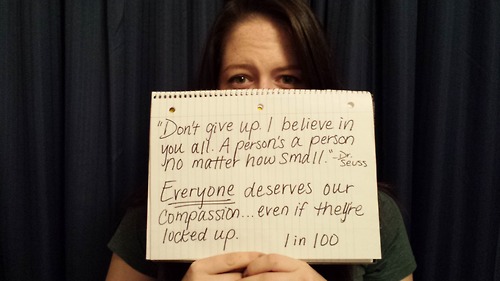

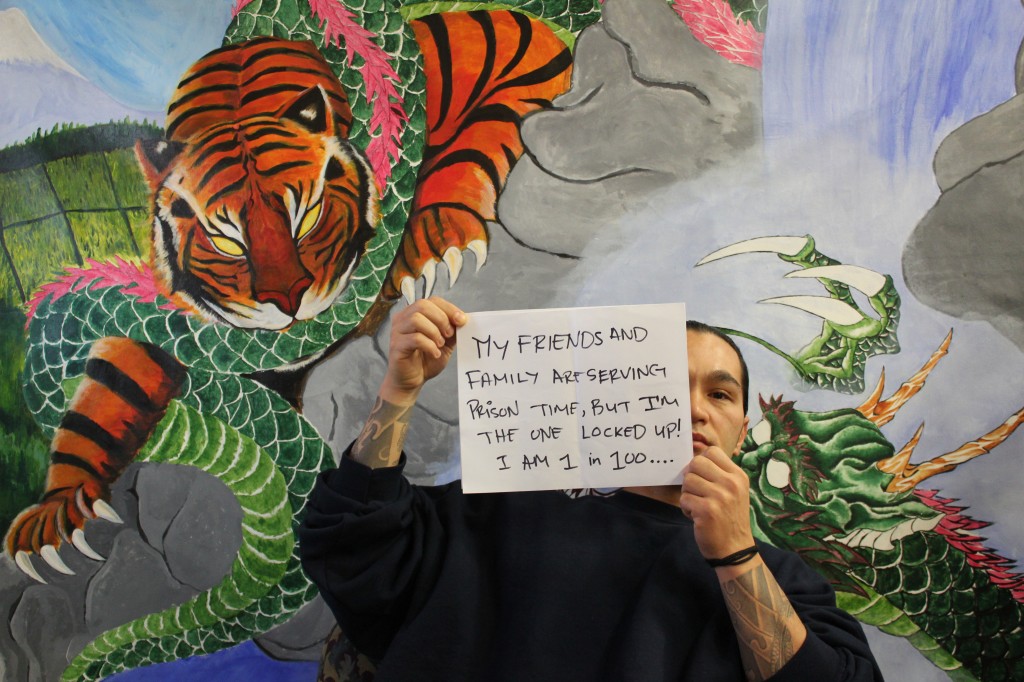

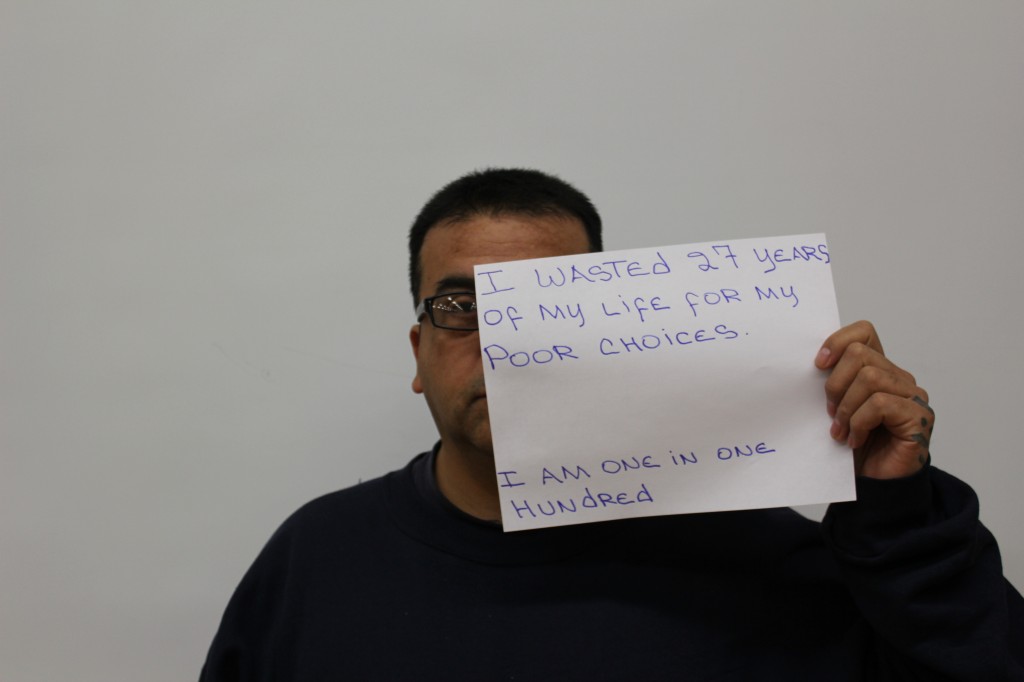

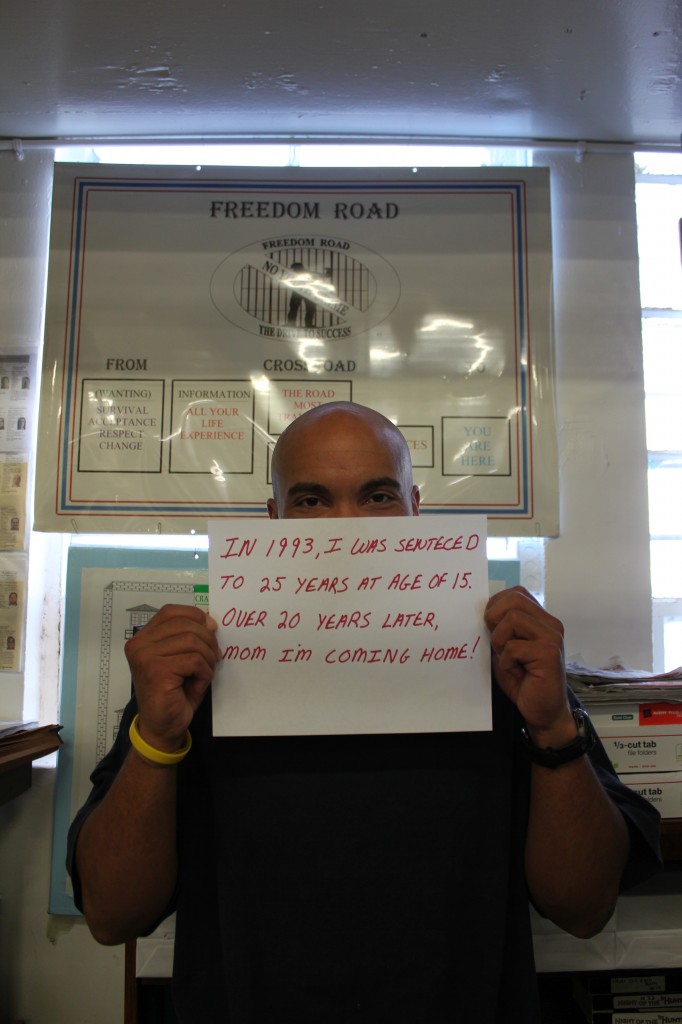

Representing the 1 in 100 Americans behind bars and those in the community who care about them and are affected by these incredible numbers, I ask my students in every Inside-Out course that I teach to share one key thought with the larger public. I’ve shared photos from my previous Inside-Out classes on this Public Criminology blog, and will continue to do so as students put time and care into their messages. This is the first time I’ve been able to put up photos of young men in the youth correctional facility. I think the first photo here is all youth and vulnerability and this particular young man makes his case eloquently. Please visit the We are the 1 in 100 tumblr site to see many more photos and sentiments of those inside and outside of correctional facilities. I invite you also to submit your own photo.

Shock, frustration, and rage. That’s our reaction to the hate-filled video record that Elliot Rodger left behind. The 22-year-old, believed to have killed 6 people in Santa Barbara last night, left behind a terrible internet trail.

Shock, frustration, and rage. That’s our reaction to the hate-filled video record that Elliot Rodger left behind. The 22-year-old, believed to have killed 6 people in Santa Barbara last night, left behind a terrible internet trail.

I cannot and will not speculate about the “mind of the killer” in such cases, but I can offer a little perspective on the nature and social context of these acts. This sometimes entails showing how mass shootings (or school shootings) remain quite rare, or that crime rates have plummeted in the past 20 years. I won’t repeat those reassurances here, but will instead address the bald-faced misogyny and malice of the videos. It outrages us to see a person look into a camera and clearly state his hatred of women — and then, apparently, to make good on his dark promises. It also raises other awful questions. Are these sentiments generally held? If you scratch the surface, are there legions of others who would and could pursue “retribution” as Mr. Rodger did? Is serious violence against women on the rise?

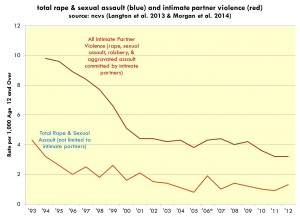

Probably not. Rates of sexual violence in the United States, whether measured by arrest or victimization, have declined by over 50 percent over the last twenty years. As the figure shows, the rape and sexual assault victimization rate dropped from over 4 per 1000 (age 12 and older) in 1993 to about 1.3 per 1000 in 2012. And, if you add up all the intimate partner violence (including all rape, sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault committed by spouses, boyfriends, or girlfriends), the rate has dropped from almost 10 per 1000 in 1994 to 3.2 per 1000 in 2012. The numbers below include male victims, but the story remains quite consistent when the analysis is limited to female victims.

Of course, misogyny and violence against women remain enormous social problems — on our college campuses and in the larger society. Moreover, the data at our disposal are often problematic and the recent trend is far less impressive than the big drop from 1993 to 2000. All that said, “retribution” videos and PUA threads shouldn’t obscure a basic social fact: 22-year-olds today are significantly less violent than 22-year-olds a generation ago.

for more on masculinity and mass violence, see There’s Research on That!

The Oregonian printed this story yesterday: “Charles Manson Family associate creates cartoon for kids who ask, ‘Why is my parent behind bars?'” Bobby Beausoleil, now 66 years old and a prisoner in the Oregon State Penitentiary, created a video meant to help answer tough questions for children of incarcerated parents. The video can be watched on Youtube and is being distributed by Parenting Inside Out, a program that helps to educate incarcerated individuals on parenting skills.

The Oregonian printed this story yesterday: “Charles Manson Family associate creates cartoon for kids who ask, ‘Why is my parent behind bars?'” Bobby Beausoleil, now 66 years old and a prisoner in the Oregon State Penitentiary, created a video meant to help answer tough questions for children of incarcerated parents. The video can be watched on Youtube and is being distributed by Parenting Inside Out, a program that helps to educate incarcerated individuals on parenting skills.

In the video, the little boy’s father is in jail; and the boy asks a professor – the blue head in the photo – questions about “bad guys.” The Oregonian offers the following excerpt from the video:

A kindly old character named Professor Proponderus offers answers.

“There are some people in the world who do bad things, son,” he says. “Sometimes a person will get scared or confused or get sick in their minds and forget who they are. People who lose their way sometimes forget what is right and wrong and why it is important to consider what is good for them and for other people. … When people forget this, they may do something that is bad.”

“Are they all in jail?” Jeeter asks.

“A lot of them are,” Professor Proponderus answers. “But not all of them.”

Jeeter eventually gets around to asking the eternal question: Is my dad bad?

“A great kid like you wouldn’t have a bad guy for a dad,” Professor Proponderus says. ” Most people are good, decent people at heart. Just because a person gets into trouble and goes to jail does not mean they are a bad person.”

Professor Proponderus tells Jeeter that people like his dad make mistakes and get “time outs” for them. The older and bigger you get, he tells young Jeeter, the bigger the consequences.

After watching the video, I’m not quite sure how I feel about it. I think this project is well-intended, but I’m not sure it quite reaches its goal(s). I would be very interested to know how children and those with an incarcerated family member react to it. Is this a useful tool for tackling these kinds of tough questions?

I hope folks are following some of the really powerful crim content on TSP these days. To name just 5…

1. The Cruel Poverty of Monetary Sanctions by Alexes Harris — a terrific piece on prisoners and debt

2. A Crimmigration roundtable, with Tanya Golash-Boza, Ryan King, and Yolanda Vázquez

3. Debt and Darkness in Detroit by David Schalliol, on streetlights and fear of crime in a bankrupt city

4. A new Crime topics page to pull all this work together, edited by Sarah Lageson and Suzy McElrath

5. Crime and the Punished, our new book volume with WW Norton!

In the wake of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s sad death, many are calling for various “harm reduction” approaches to substance use. Proponents of harm reduction have identified lots of ways to reduce the social and personal costs of drugs, but they often require us to shift our focus from the prevention of drug use itself to the prevention of harm. Resistance to such approaches often hinges on the notion that they somehow tolerate, facilitate, or even subsidize risky behavior.

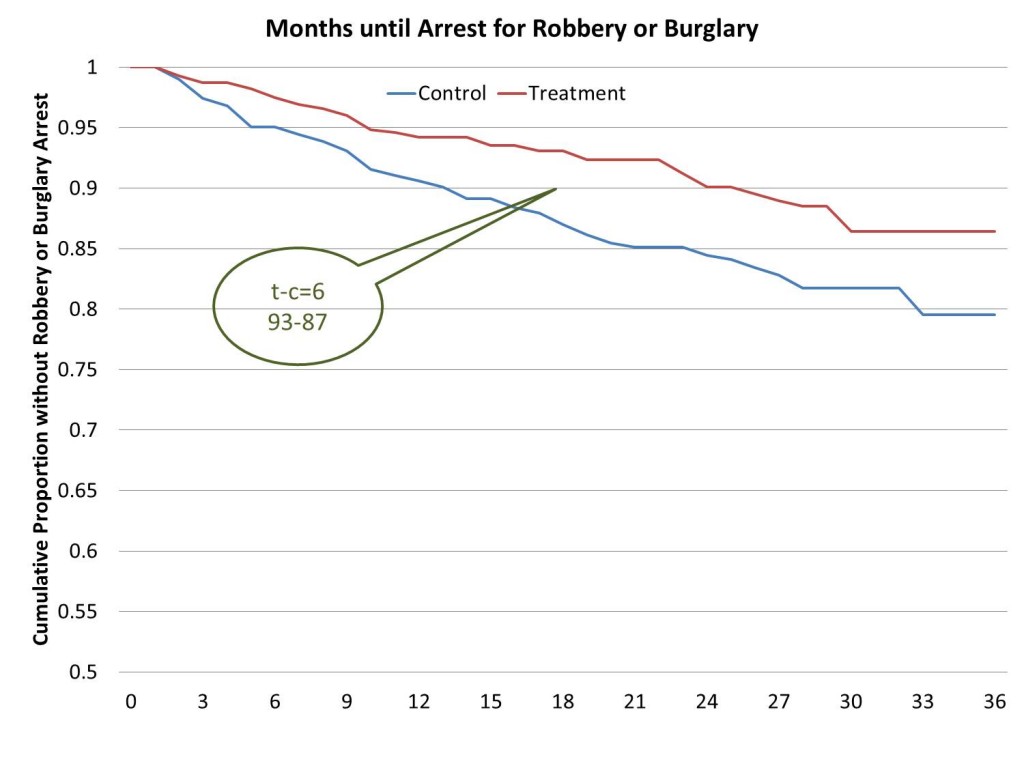

This tension emerged clearly in my new article with Sarah Shannon in Social Problems. We re-analyzed an experimental jobs program that randomly assigned a basic low-wage work opportunity to long-term unemployed people as they left drug treatment. In some ways, the program worked beautifully. The job treatment group had significantly less crime and recidivism, especially for predatory economic crimes like robberies and burglaries. After 18 months, about 13 percent of the control group had been arrested for a new robbery or burglary, relative to only 7 percent of the treatment group. Put differently, 87 percent of those not offered the jobs survived a year and a half without such an arrest, relative to 93 percent of the treatment group who were offered jobs.

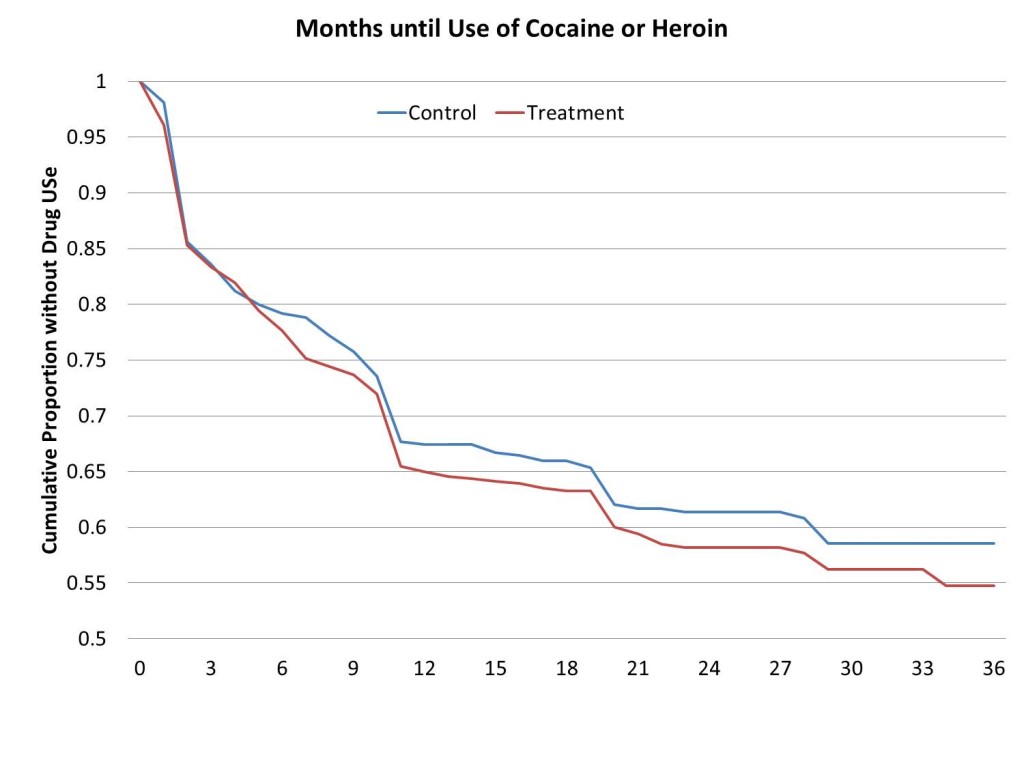

A randomized experiment that shows a 46 percent reduction in serious crime is a pretty big deal to criminologists, but the program has still been considered a failure. In part, this is because the “treatment” group who got the jobs relapsed to cocaine and heroin use at about the same rate as the control group. After 18 months, about 66 percent of the control group had not yet relapsed, relative to about 63 percent in the treatment group. So, there’s no evidence the program helped people avoid cocaine and heroin.

From an abstinence-only perspective, such programs look like failures. Nevertheless, even a crummy job and a few dollars clearly helped people avoid recidivism and improved the public safety of their communities. So, did the program work? From a harm reduction perspective, a jobs program for drug users surely “works” if it reduces crime and other harms, even if it doesn’t dent rates of cocaine or heroin use.

Productive Addicts and Harm Reduction: How Work Reduces Crime – But Not Drug Use

Christopher Uggen and Sarah K. S. Shannon

Social Problems

Vol. 61, No. 1 (February 2014) (pp. 105-130)From the Works Progress Administration of the New Deal to the Job Corps of the Great Society era, employment programs have been advanced to fight poverty and social disorder. In today’s context of stubborn unemployment and neoliberal policy change, supported work programs are once more on the policy agenda. This article asks whether work reduces crime and drug use among heavy substance users. And, if so, whether it is the income from the job that makes a difference, or something else. Using the nation’s largest randomized job experiment, we first estimate the treatment effects of a basic work opportunity and then partition these effects into their economic and extra-economic components, using a logit decomposition technique generalized to event history analysis. We then interview young adults leaving drug treatment to learn whether and how they combine work with active substance use, elaborating the experiment’s implications. Although supported employment fails to reduce cocaine or heroin use, we find clear experimental evidence that a basic work opportunity reduces predatory economic crime, consistent with classic criminological theory and contemporary models of harm reduction. The rate of robbery and burglary arrests fell by approximately 46 percent for the work treatment group relative to the control group, with income accounting for a significant share of the effect.

Another of the projects my Inside-Out students took on this term was to create beautiful hand-decorated holiday cards for children visiting the Oregon State Penitentiary to take home with them, personalize, and mail back to their fathers, uncles, and other loved ones. OSU (outside) student Lexie explains the rationale for these card packets:

Another of the projects my Inside-Out students took on this term was to create beautiful hand-decorated holiday cards for children visiting the Oregon State Penitentiary to take home with them, personalize, and mail back to their fathers, uncles, and other loved ones. OSU (outside) student Lexie explains the rationale for these card packets:

These packets were made by the Inside-out class of fall 2013. These packets will be given to the children of inmates at OSP so that they may have a stamped, addressed, decorated card to send to a loved one with little to no barriers. It also included candy, extra writing paper and an extra envelope. Receiving things from family members on the outside means a lot to these guys and helps them to keep their heads up while working to improve their own lives and the lives of others for the duration of their sentences. Most of these examples of the cards are done by inmates and are beautiful. There are some that are not that great, haha, but have potential for the kids to make them great. These aren’t all of them, but a few we picked out to share.

It’s a small but important way for us to continue to support men in prison (including our own inside students) and the children who love them.

The We are the 1 in 100 tumblr site is an ongoing project of my Inside-Out classes, with submissions representing both the approximately 1 in 100 Americans behind bars and those affected by their incarceration. The Fall 2013 inside and outside students have recently added some powerful new sentiments and images. Check it out.

I was fortunate to host one of the more meaningful Halloween events of my life this year. Building on the work I have been doing in one of our state youth correctional facilities over the past couple of years, I approached the administration with the idea of holding a Halloween party for the incarcerated fathers and their young children. The fathers, themselves, are in their late teens and early twenties, so their children are all very young and at the age when Halloween is a major holiday.

I was fortunate to host one of the more meaningful Halloween events of my life this year. Building on the work I have been doing in one of our state youth correctional facilities over the past couple of years, I approached the administration with the idea of holding a Halloween party for the incarcerated fathers and their young children. The fathers, themselves, are in their late teens and early twenties, so their children are all very young and at the age when Halloween is a major holiday.

We arranged to have the event on October 30th, so that it was an additional celebration and did not take the kids away from their own neighborhood celebration of Halloween. Approximately seven young fathers participated, and family members brought their young children in their Halloween costumes into the facility to decorate pumpkins with their dads, decorate and eat cookies together, and to try to catch donuts and apples on strings (a more hygienic version of bobbing for apples). The culminating event was when the kids and their dads were able to trick or treat down the hallways of the institution’s school. I had eight fabulous students from Oregon State University helping to run the event – the OSU volunteers were able to each go into a classroom and greet the little trick-or-treaters with kindness and candy. After the little kids went home, we invited the full population of the facility to join us in the gym for pumpkin decorating, lively games, cookies, and candy. I think it’s safe to say that the OSU volunteers and the young men in the facility all had a great time.

In the grand scheme of things, this event was a little thing that the youth correctional facility made possible. All we had to do was suggest the idea; they then allowed us to make the plans, and then the administrators made it happen. In the past 20 years (at least), they have never had an event like this. For the kids and dads who participated, this was a big deal. The dads got to be involved in an important childhood ritual, and they were able to make some unique memories with their kids. I got to play photographer for much of the event, and I took some great family photos that both the kids and dads will be able to look back upon and enjoy for many years to come.

In my research and teaching, I think a lot about at-risk youth and children of incarcerated parents. Small events like this one seem to me to be a small but important step to show that the community cares and wants what is best for these children. It was a Halloween well spent.

Few (if any) of us have abstained from crime completely. And recognizing our own criminality is often an important first step in understanding the situation of those who are caught and punished for crimes. I use self-report delinquency surveys to show this commonality to my students, but the traveling exhibit We Are All Criminals makes the point far more emphatically.

Few (if any) of us have abstained from crime completely. And recognizing our own criminality is often an important first step in understanding the situation of those who are caught and punished for crimes. I use self-report delinquency surveys to show this commonality to my students, but the traveling exhibit We Are All Criminals makes the point far more emphatically.

The multimedia project tells our stories — the millions of people who have committed felonies and misdemeanors but managed to avoid the stigma of a criminal record. Its architect is Emily Baxter, a visionary Minnesota attorney and Director of Public Policy and Advocacy at the Council on Crime and Justice. From the site:

Participants in We Are All Criminals tell stories of crimes they got away with… The participants are doctors and lawyers, social workers and students, retailers and retirees who consider how very different their lives could have been had they been caught. The photographs, while protecting participants’ identities, convey personality: each is taken in the participant’s home, office, crime scene, or neighborhood. The stories are of youth, boredom, intoxication, and porta potties. They are humorous, humiliating, and humbling in turn. They are privately held memories without public stigma; they are criminal histories without criminal records.

We Are All Criminals seeks to challenge society’s perception of what it means to be a criminal and how much weight a record should be given, when truly – we are all criminals. But it is also a commentary on the disparate impact of our state’s policies, policing, and prosecution: many of the participants benefited from belonging to a class and race that is not overrepresented in the criminal justice system. Permanent and public criminal records perpetuate inequities, precluding thousands of Minnesotans from countless opportunities to move on and move up. We Are All Criminals questions the wisdom and fairness in those policies.

You can see much of the project online, attend one of the public events, or attend Ms. Baxter’s presentation at the American Society of Criminology meetings in Atlanta this November 23rd.