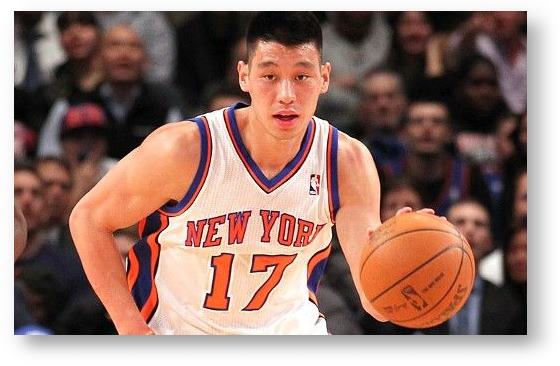

In my recent post titled, “Jeremy Lin Mania and How it Relates to Colorblindness,” among other things, I noted that Jeremy’s emergence as a media sensation and explosion onto the center stage of mainstream U.S. popular culture does represent a small step toward the eventual ideal of colorblindness. At the same time, I also argued that the reality is that unfortunately, we are still a long way from being a truly colorblind society.

This past week, several public incidents have solidified the sad fact that many Americans still think that we are already in a colorblind society and as such, they can basically say anything they want about Jeremy, including offensive references to him as a Chinese American. Unfortunately there have been several examples of racial insensitivity in the past couple of weeks, but in this post I will focus on two in particular.

First, after the Knicks defeated the Los Angeles Lakers in which Jeremy scored 38 points, FoxSports.com columnist Jason Whitlock tweeted “Some lucky lady in NYC is gonna feel a couple inches of pain tonight.” Whitlock later apologized for the remark, but you can’t unring that bell — clearly he thought it was perfectly acceptable to invoke the emasculating racial stereotype about Asian men having small penises.

But wait, there’s more.

A few days later, after Jeremy committed nine turnovers in a game that the Knicks eventually lost, thereby snapping their 7-game winning streak, the following headline made it onto ESPN’s mobile website (screenshot below): “Chinks in the Armor: Jeremy Lin’s 9 Turnovers Cost Knicks in Streak-Snapping Loss to Hornets.”

The headline was apparently taken down after being public for 35 minutes but again, the damage was done — the editors at ESPN apparently had no idea or did not care that the term “chink” is a blatantly racist term against all Asian Americans but particularly and deeply offensive to Chinese Americans. I might expect people outside the U.S., such as Spain’s national basketball team, not to know that the term “chink” is racist, but it is very disappointing to learn that many Americans still think it’s perfectly fine to use in reference to a Chinese American.

Disappointing, but unfortunately not really surprising.

That is because many Americans already believe, consciously or unconsciously, that we are already a colorblind society. As such, they have been taught, socialized, and desensitized to naively think that all racial groups are equal now, that no racial discrimination ever takes place nowadays, and therefore, it’s fine to casually use terms such as “chink” in everyday conversation.

These particular incidents may not be as blatantly offensive as the racial taunts Jeremy encountered back when he played for Harvard, but they nonetheless illustrate a woeful level of ignorance and lack of sensitivity about Asian Americans, our history, and our community.

Imagine what the public’s reaction would have been if Jason Whitlock was referring to a Black player and his remark invoked the racial stereotype about Black men having large penises. What would the public’s reaction had been if ESPN went public with some headline that referred to a Black player using the ‘N’ word? I think it would be safe to say that the American public would be shocked, outraged, and furious if these hypothetical examples occurred in reference to a Black player.

To Whitlock’s and ESPN’s credit, they both apologized and in ESPN’s case, fired the person responsible for the website headline and suspended one of their sportscasters, Max Bretos, who repeated the “chink in the armor” phrase on air. To be honest, I was pleasantly surprised at how quickly and decisively ESPN acted in regard to these incidents. In the past, more than likely, ESPN would have taken days to issue a half-hearted apology and probably would not have disciplined any of their staff involved. I suppose ESPN’s actions in this matter do represent an encouraging sign of progress.

Fortunately, there are others in the mainstream media who “get it” — those who understand the contradiction and inequality that exist when such racial/ethnic stereotypes are in reference to, say Blacks, versus when they reference Asian Americans. Specifically, leave it the crew at Saturday Night Live to use comedy and satire to deftly illustrate this contradiction:

So I suppose that it does represent progress that when these types of racially ignorant incidents happen, the mainstream media nowadays does recognize it and take disciplinary action (or use satire to point out the absurdity of such ignorance) more quickly than in the past. Now if we can just get to the point where such incidents don’t happen in the first place.

This article originally published at Asian-Nation.org and is copyrighted © 2013