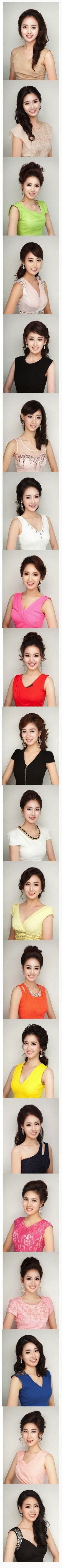

I was doing my daily browsing of Reddit, the popular online news, humor, and information aggregation site, and came across this submission that caused me to do a double-take: Korea’s Plastic Surgery Mayhem is Finally Converging on the Same Face: Miss Korea 2013 Contestants. The picture on the right shows the 21 contestants of the Miss Korea 2013 beauty pageant.

Although there are differences in hairstyle and dress, at least when it comes to the contestants’ faces, I have to say that I agree with the page’s consensus that all the women look virtually the same.

Physical Homogeneity and the Yellow Peril

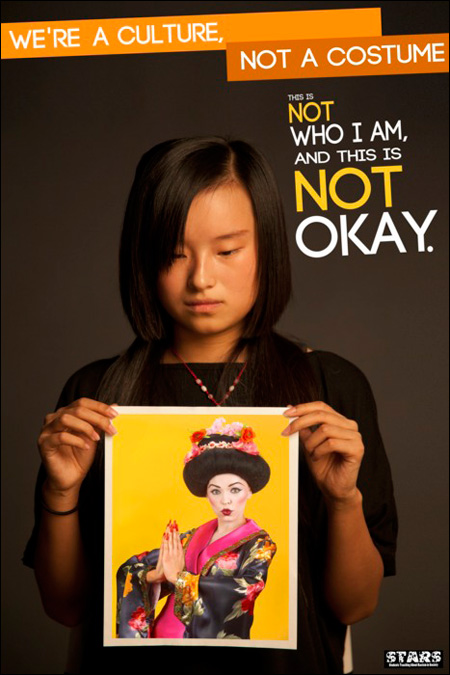

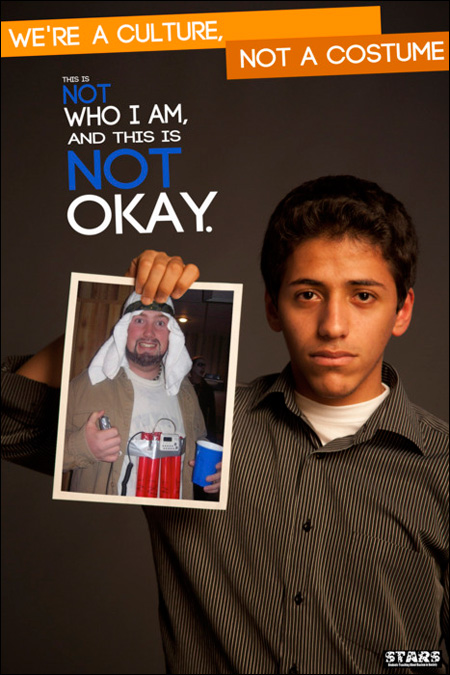

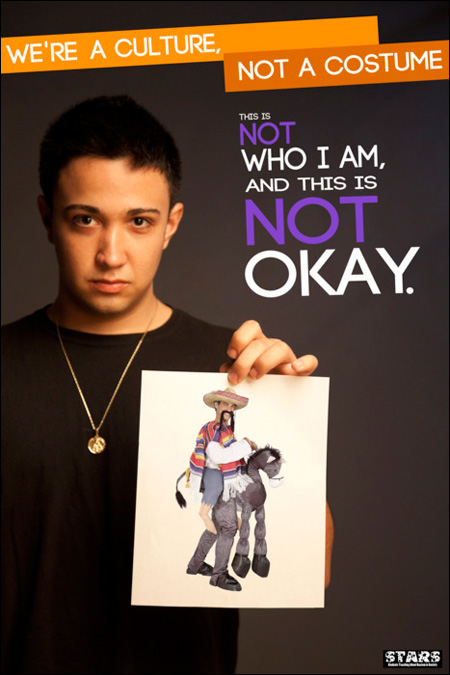

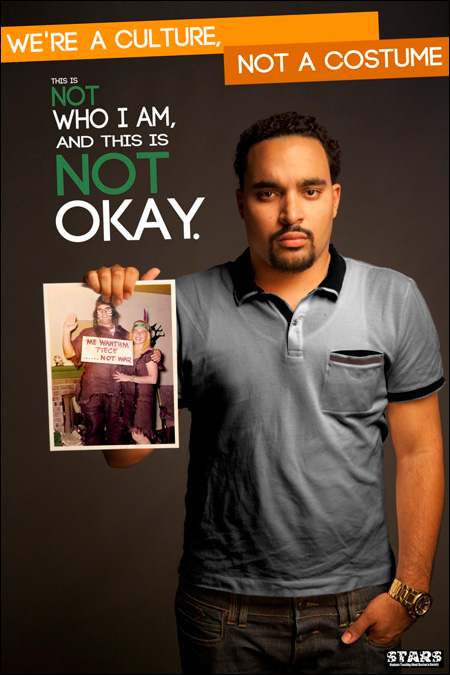

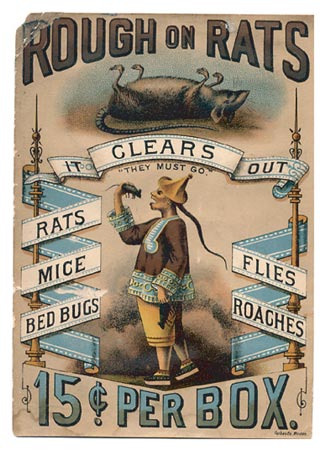

As such, this brings up a few different implications. The first, as mentioned in several of the Reddit comments, is that it seems to reinforce the unfortunate stereotype that all Asians look the same. On the one hand, there tends to be a certain degree of visual conformity and homogeneity in beauty pageants in general, but as many Asian Americans can attest to, this particularly stereotype about all Asians looking the same unfortunately feeds into the image of us as the Yellow Peril — the depiction of Asians as a faceless and almost sub-human mass bent on attacking, taking over, and/or destroying U.S. society, its economy, and culture.

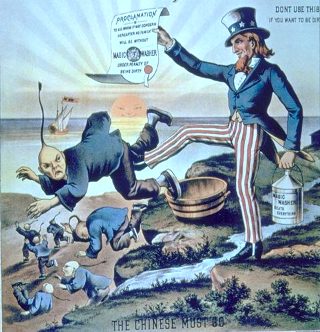

This imagery of Asians as the Yellow Peril can be seen in the graphic below from the 1800s, which is actually a magazine advertisement for soap (that’s what Uncle Same is holding in his left hand). The image’s main focus however, is on him kicking out the Chinese out of the country toward the squinty-eyed sun in the horizon. Just as important is the imagery of physically indistinguishable Chinese scurrying into the background, the Yellow Peril vanquished by American might and superiority. As described elsewhere on this blog, this stereotype that all Asians are the same has also led to many tragic instances of blatant bigotry, discrimination such as racial profiling, and even violence.

Conformity to Western Beauty Standards

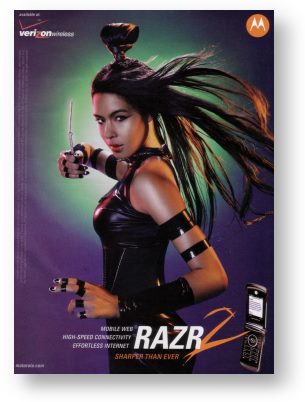

Secondly, the image of the Miss Korea 2013 contestants brings up the question of whether Asians and Asian Americans are implicitly or explicitly conforming to dominant western standards of physical beauty. Within the Asian American community, this question has taken the form of the debate about the cultural implications of Asian Americans getting cosmetic surgery and in particular, whether procedures such as double-eyelid surgery, breast augmentation, and using products to whiten one’s skin represent conforming to western standards of beauty. This question is highlighted in a segment from ABC’s NightLine from a couple of years age:

Of course, there are passionate opinions on both sides of this debate about these particular cosmetic procedures represent conforming to western standards of beauty, but more generally, I would venture to say that most people, Asian American and otherwise, would agree that westerns ideals of beauty are still a dominant force in the media and fashion industries in industrialized nations around the world and do indeed exert an influence on how young Asian American women judge themselves and their physical appearance.

The downside to such pressures can often be disastrous for Asian American women and take such forms as eating disorders, depression, and when combined with other pressures to conform to the model minority image, even suicide.

The Ironies of Multiculturalism

The irony in all of this is that, in the context of globalization, multiculturalism, and increased racial/ethnic diversity in U.S. society, our society has generally been more open and likely to recognize and celebrate more diverse forms of cultural representation. But one area in which this does not seem to be the case is standards of physical beauty where western and White images and idealizations still predominate. Even in the ABC NightLine video segment above, while the overall trend is toward greater inclusion of Asian and Asian American models in the fashion industry, the reality of their portrayals have included an underlying profit motive to tap into the burgeoning Asian consumer market and (inadvertently?) homogenizing the models.

Going back to the contestants of the Miss Korea 2013 pageant, like most people, I would certainly concur that the young women are all attractive just based on their physical appearance. Nonetheless, I hope that Korean and western societies in general will eventually acknowledge and appreciate that beauty can take many diverse forms and can wear more than just one face.

I am very pleased to report that this post is the 1,000th post published on the Asian-Nation blog. Thank you for helping to keep Asian-Nation going strong since 2001 and here’s to the next 1,000 posts and beyond!