The #MeToo movement that began in 2017 has reignited a long debate about how to name people who have had traumatic experiences. Do we call individuals who have experienced war, cancer, crime, or sexual violence “victims”? Or should we call them “survivor,” as recent activists like #MeToo founder Tarana Burke have advocated?

Strong arguments can be raised for both sides. In the sexual violence debate, advocates of “survivor” argue the term places women at the center of their own narrative of recovery and growth. Defenders of victim language, meanwhile, argue that victim better describes the harm and seriousness of violence against women and identifies the source of violence in systemic misogyny and cultures of patriarchy.

Unfortunately, while there has been much debate about the use of these terms, there has been little documentation of how service and advocacy organizations that work with individuals who have experienced trauma actually use these terms. Understanding the use of survivor and victim is important because it tells us what these terms to mean in practice and where barriers to change are.

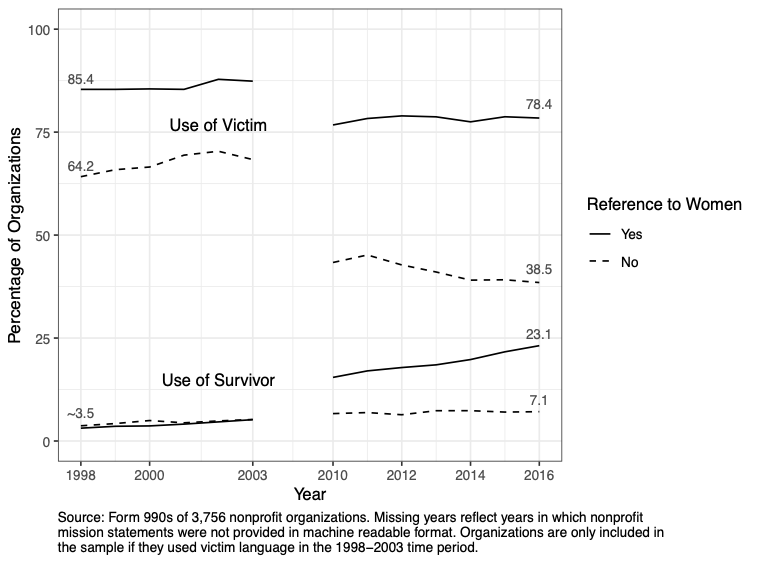

We sought to remedy this problem in a recent paper published in Social Currents. We used data from nonprofit mission statements to track language change among 3,756 nonprofits that once talked about victims in the 1990s. We found, in general, that relatively few organizations adopted survivor as a way to talk about trauma even as some organizations have moved away from talking about victims. However, we also found that, increasingly, organizations that focus on issues related to women tend to use victim and survivor interchangeably. In contrast, organizations that do not work with women appear be moving away from both terms.

These findings contradict the way we usually think about “survivor” and “victim” as opposing terms. Does this mean that survivor and victim are becoming the “extremely reduced form” through which women are able to enter the public sphere? Or does it mean that feminist service providers are avoiding binary thinking? These questions, as well as questions about the strategic, linguistic, and contextual reasons that organizations choose victim- or survivor-based language give advocates and scholars of language plenty to re-examine.

Andrew Messamore is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. Andrew studies changing modes of local organizing at work and in neighborhoods and how the ways people associate shapes community, public discourse, and economic inequality in the United States.

Pamela Paxton is the Linda K. George and John Wilson Professor of Sociology at The University of Texas at Austin. With Melanie Hughes and Tiffany Barnes, she is the co-author of the 2020 book, Women, Politics, and Power: A Global Perspective.