Why did people march on January 21, 2017? As a team of sociologists interested in social movements, we know there are many possible answers to this seemingly simple question.

As a team of sociologists we have developed a multi-method, multi-site research project, Mobilizing Millions: Engendering Protest Across the Globe.* We want to understand why people participate in a march of this scale, at a critical historical juncture in our political landscape. Within weeks of discussion of the first march, there were already “sister” march pages national and internationally. While it is beyond the scope of this post to discuss all of the project findings thus far, the predictability of the racial tensions visible in social media or the role of men, local opportunities and challenges we do offer some early findings.

In the project’s first phase, we had team members on the ground in Washington D.C.; Austin, TX; Boston, MA; Los Angeles, CA; New York, NY; Philadelphia, PA; Portland, OR; Santa Barbara, CA and St. Louis, MO. We are currently conducting a survey about the motivations and experiences that brought millions of people to the marches worldwide. We recruited respondents from marches in the aforementioned cities, and online. This has resulted in responses from around the world. Our preliminary findings from the observations and survey highlight that 1) there were a range of reasons people attended marches and 2) across and within sites, there were varying experiences of “the” march in any location.

One striking similarity we observed across sites was the limited visible presence of social movement organizations (SMOs). For sure, SMOs became visible in social media leading up to the event (particularly for the DC march). Unlike at social movement gatherings such as the US Social Forum or conservative equivalents, the sheer number of unaffiliated people dwarfed any delegations or representatives from SMOs. Of our almost 60-member nation-wide team across sites only a handful had encountered anyone handing out organizational material, as we would see at other protest. This is perhaps what brought many people to the march—an opportunity to be an individual connecting with other individuals. However, this is an empirical question as is what this means for the future of social movement organizing. We hope others join us in answering.

Second, while the energy was palpable at all of the marches so was the confusion. As various media sources reported, attendance at all sites far exceeded projections, sometimes by 10 times. Consequently, the physical presence of the expanded beyond organizers’ expectations, which in many places required a schedule shifted. At all marches there were points where participants in central areas could not move and most people could not hear scheduled speakers even if they were physically close to a stage. Across the sites, we also observed how this challenge stimulated different responses. In multiple locations, people gathering spontaneously created their own sub-marches out of excitement as happened in DC when a band started playing on Madison street and people followed. Or, while waiting, waiting participants chanted “march, march.” Still, in many locations, once the official march started, people created sub-marches out of necessity because the pre-planned march route was impassable. When faced with standing for an hour to wait their “turn” to walk or create an alternative, they chose the latter.

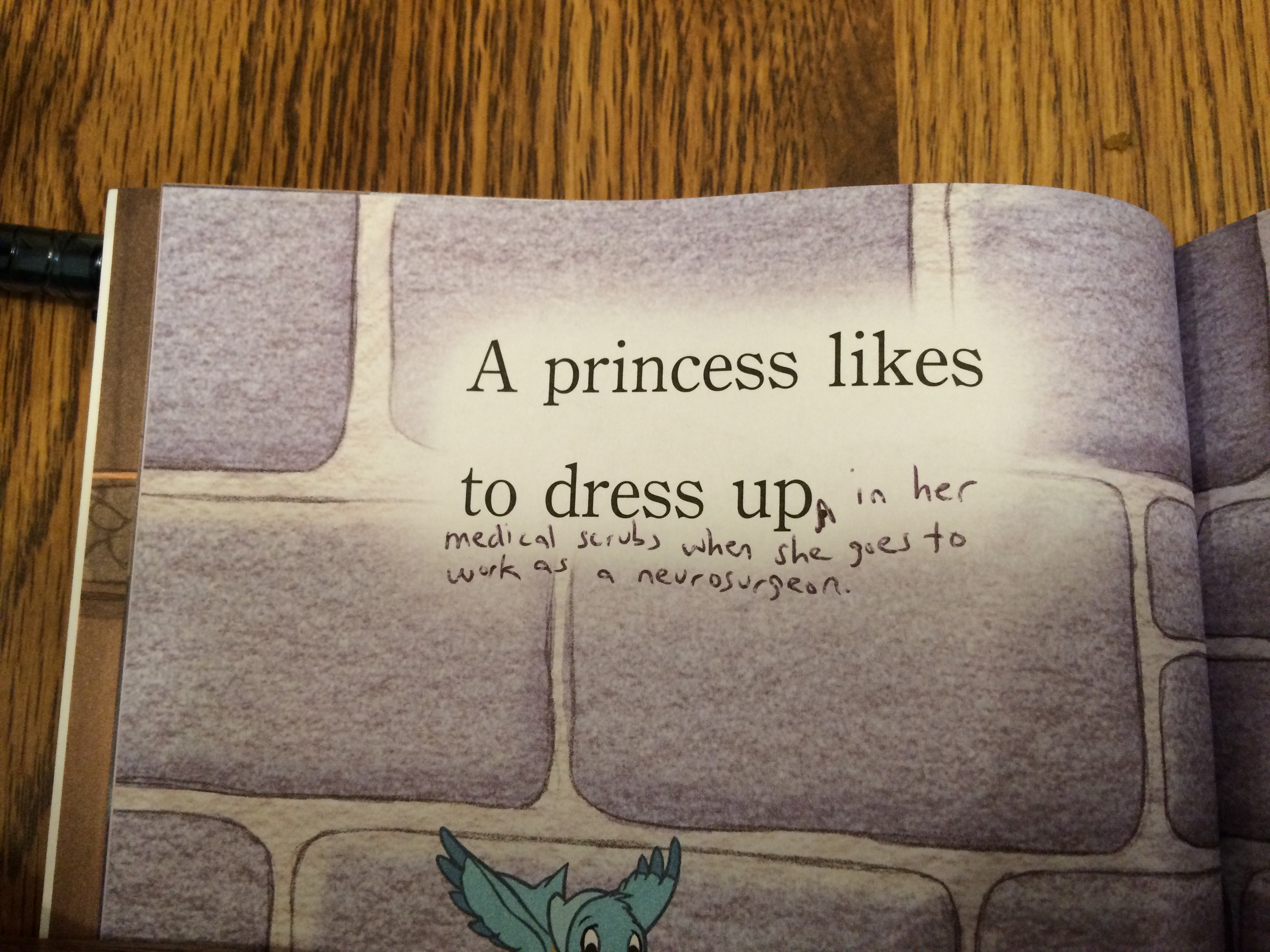

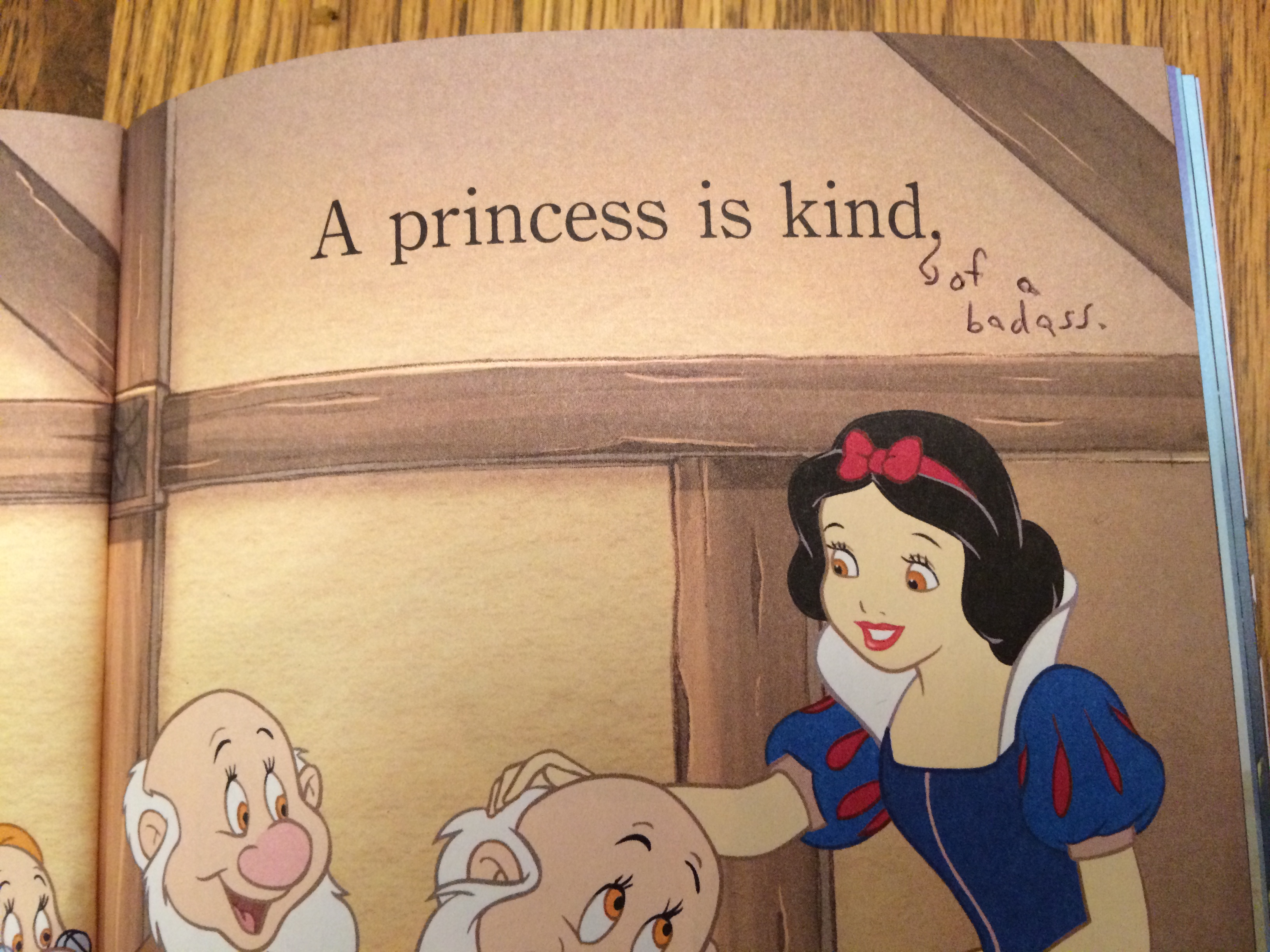

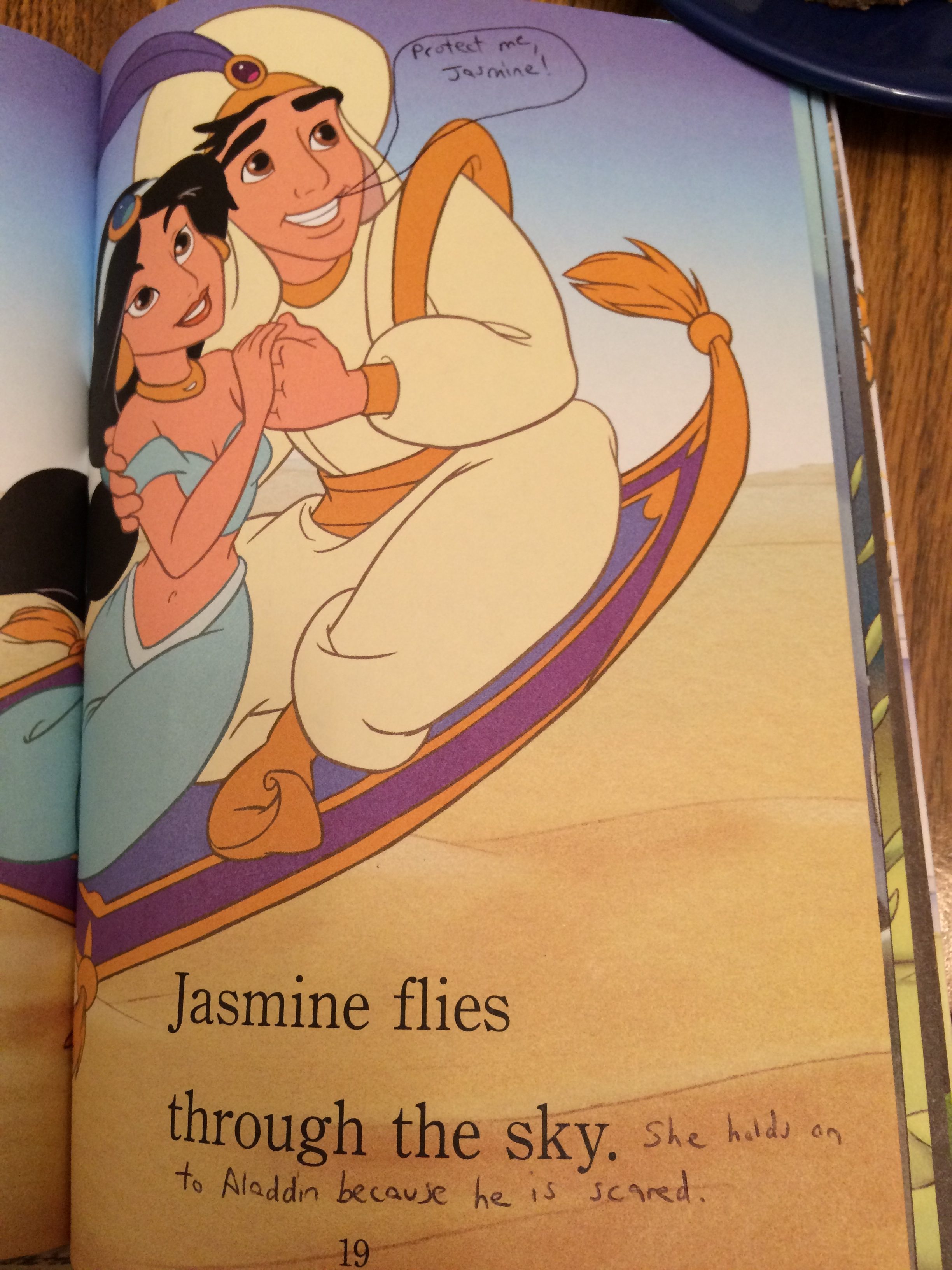

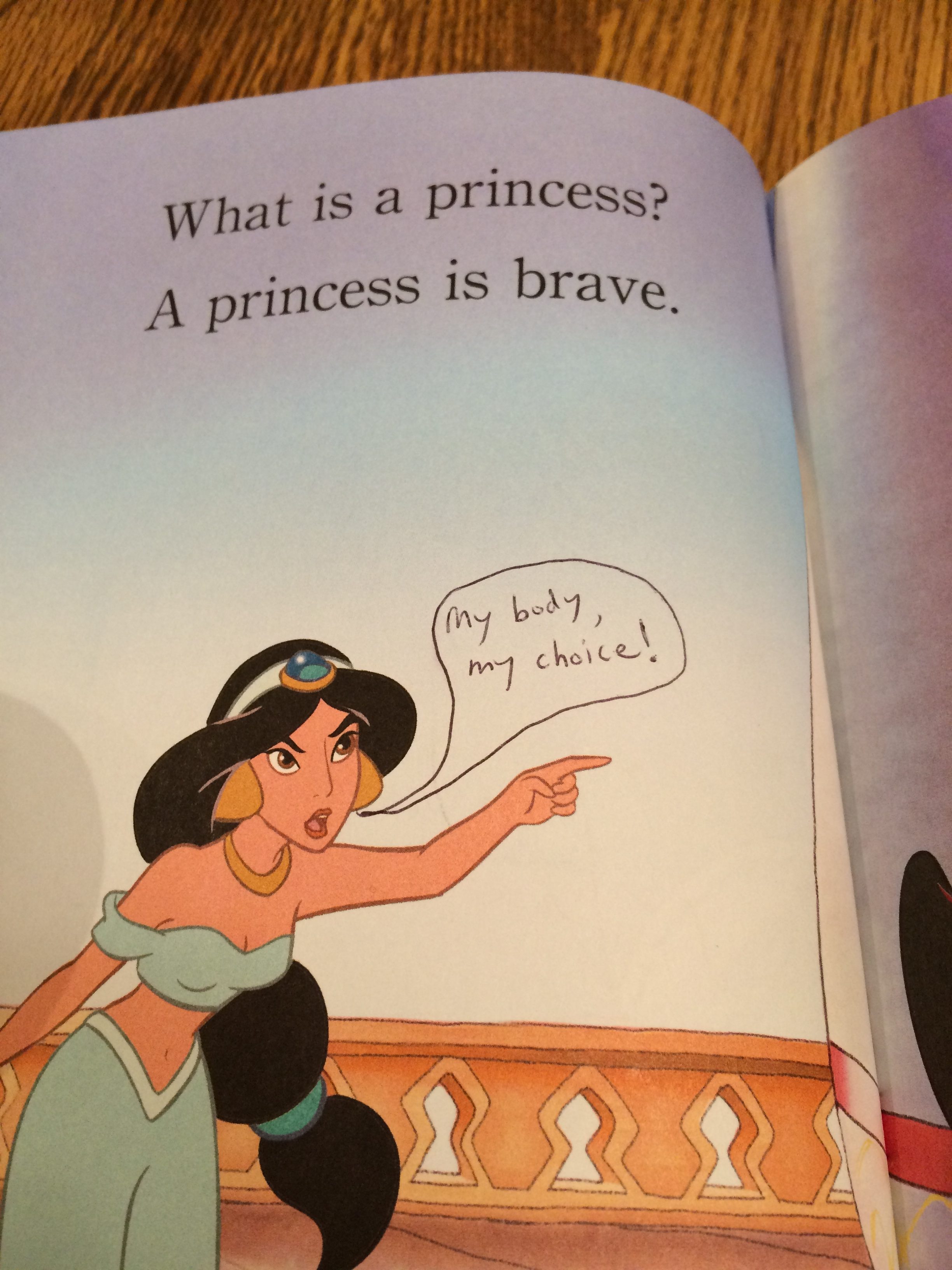

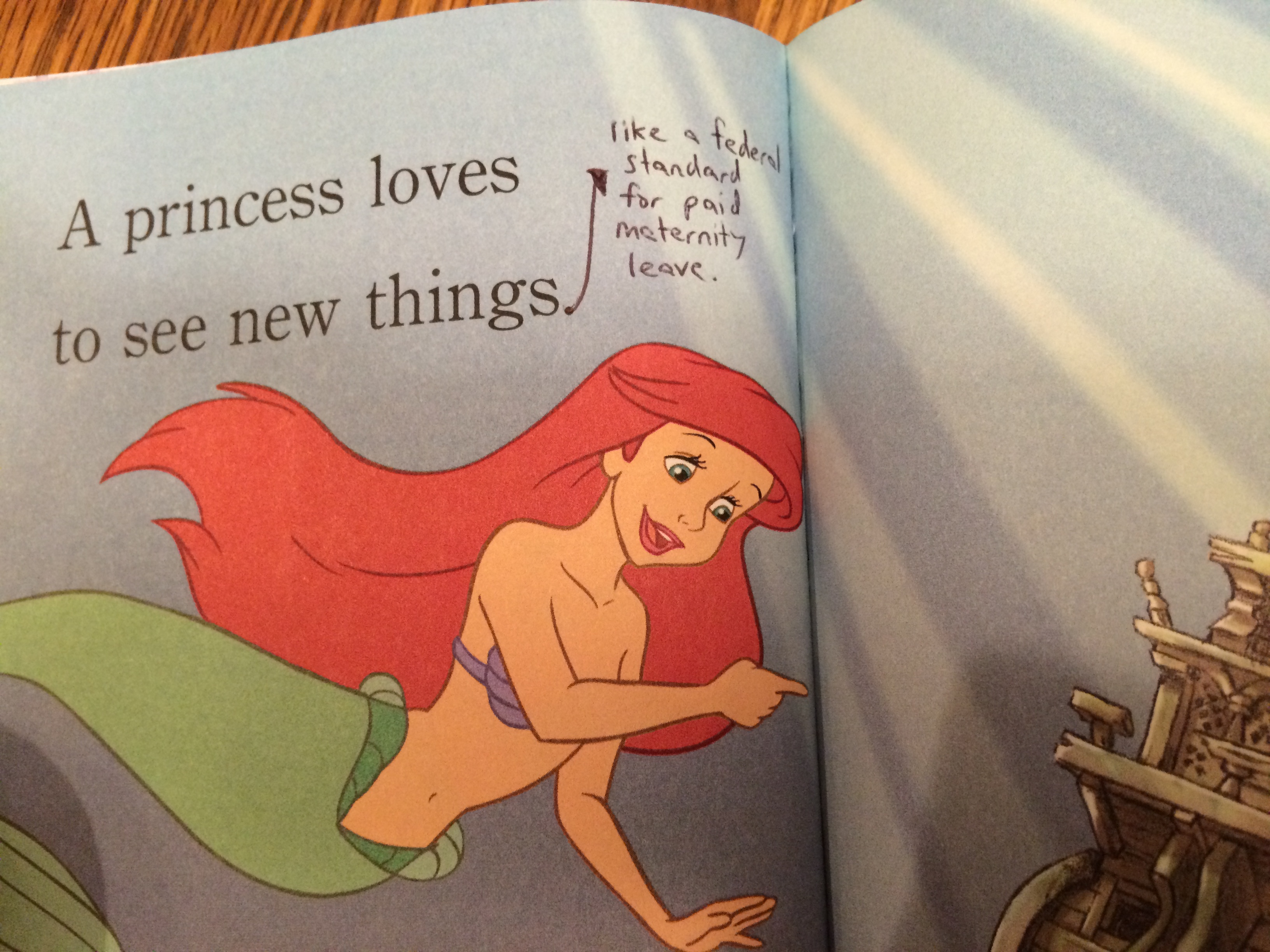

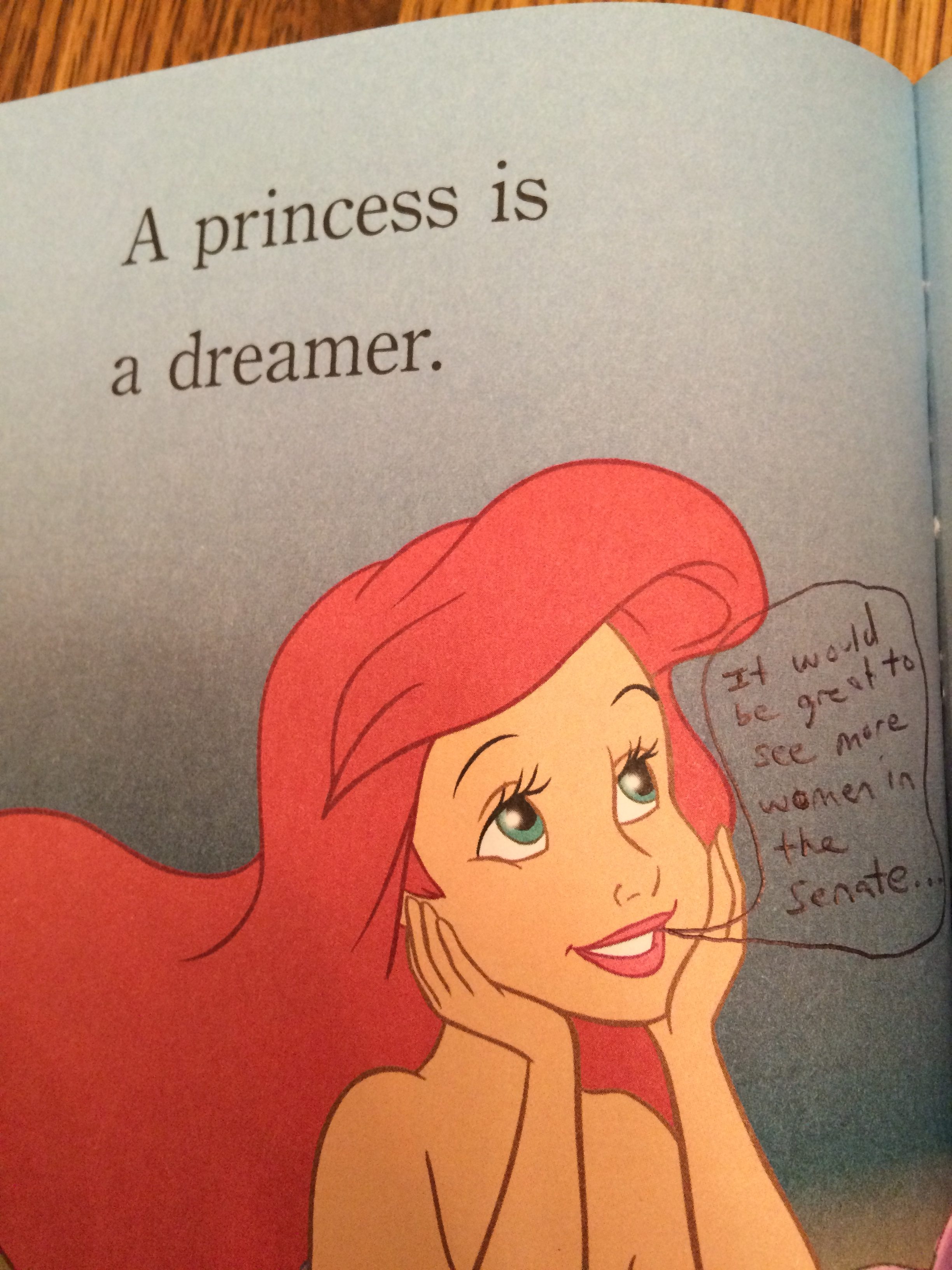

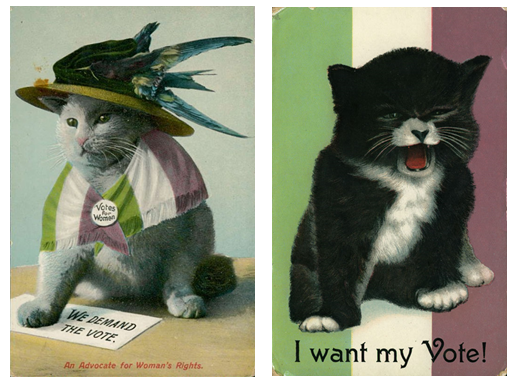

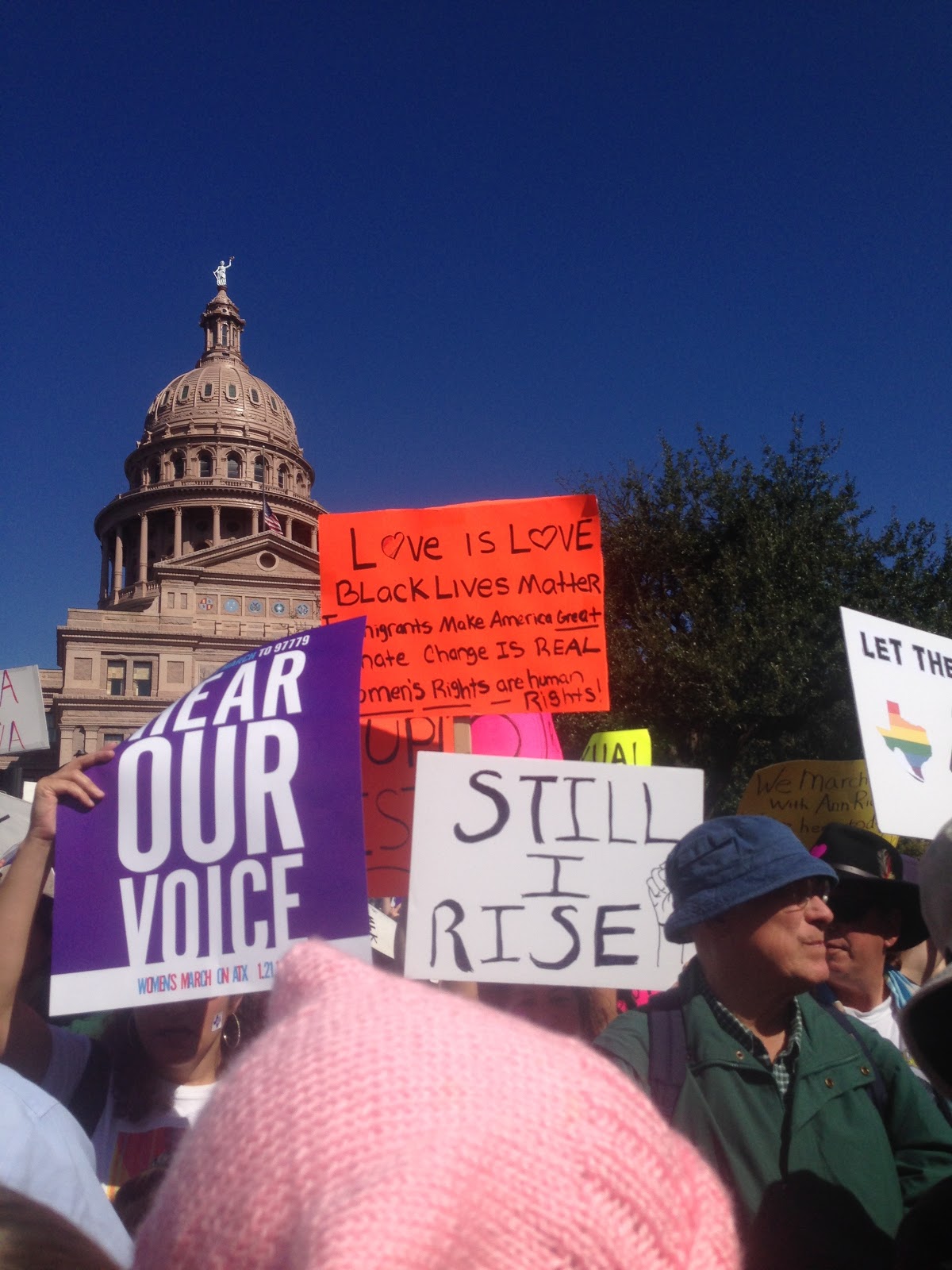

Creativity was visible in artistic forms as well. While there were professionally printed signs (and T-shirts), there was a wealth of handmade signs at the marches. As expected, a slew that referenced phrases the president-elect had said noting, for example, “this pussy grabs back.” Yet there was also a range of other signs ranging from simple text to complicated storyboards (see below).

Across sites, we also saw many differences: including which types of organizations sponsored (or “supported” or “ were affiliated with”) that march.

At the Austin, Texas march, marchers’ signs and chants reflected a wide variety of concerns, including women’s reproductive health care, Black Lives Matter, and environmental justice. The emotional tenor was frequently celebratory, though it varied from one point in the march to another across a crowd reported to be more than 40,000. Many speeches at the rally immediately following the march connected the actions of the Texas state legislature–on whose front steps the march began and ended–to the broader national context.

The Los Angeles March numbers suggest it exceeded DC participation. There was a noticeable presence of signs about immigration and in Spanish, which is not surprising considering the local and state demographics.

The Philadelphia, PA march was close to bigger cities of in New York and DC. Some participants noted that due to the location it was “competing” for marchers.

The Portland, OR protest also exceeded attendance expectations as marchers withstood hours of pouring rain. Holding the “sister” marches on the same day worldwide emphasized the magnitude and assists in building collective identity. Yet it also meant organizers in different locations faced vastly different challenges. Factors such as weather that might not have existed if organizers had been scheduling based solely on local norms and contexts.

To help provide a preliminary sense of the motivations and continued engagement of marchers, we examined a sample of the ~40,000 tweets posted over two months. The analysis continues.

In the coming month, we are launching a separate survey to better understand a group social movement scholars are sometimes less inclined to study: people who do not participate in marches on January 21 (there are exceptions to this of course). As social movement scholars know, mobilization is actually a rare occurrence when we consider the range of grievances present in any society at any given moment. For a second phase of the project, we will conduct interviews with select survey participants.

Understanding the range of responses to grievances is critical as we move into this new era. If the first month of Trump’s presidency is any indication of the years to come, scholars and activists across the political spectrum will have many opportunities to engage these questions.

____________________

*The team Faculty collaborators are Zakiya Luna, PhD (Principal Investigator, California, DC, LA,PH and TX coordinator); Kristen Barber, PhD (St. Louis Lead); Selina Gallo-Cruz, PhD (Boston Lead); Kelsy Kretschmer, PhD (Portland Lead). The site leadership was provided by Anna Chatillon (Austin, TX); Fátima Suarez (Los Angeles, CA); Alex Kulick (Philadelphia, PA & social media); Chandra Russo, PhD (DC co-lead). We are also grateful to many volunteer research assistants.

Dr. Zakiya Luna is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at University of California, Santa Barbara. Her research focused on social movements, human rights and reproduction with an emphasis on the effects of intersecting inequalities within and across these sites. She has published multiple articles on activism, feminism and reproductive justice. For more information on her research and teaching, see http://www.zakiyaluna.com.

Alex Kulick, MA, is a doctoral student in sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara and trainee in the National Science Foundation network science IGERT program. Their research investigates social processes of inequality and resistance with an emphasis on sexuality, gender, and race.

Anna Chatillon-Reed is a doctoral student in sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is currently completing her MA, which investigates the relationship between the Black Lives Matter movement and feminist organizations.

In his speech accepting the Republican nomination for President, Donald Trump

In his speech accepting the Republican nomination for President, Donald Trump