To mark the end of Women’s History Month, we offer this compilation of our posts on women and history.

- The Manly Origins of Cheerleading (1800s-2000s)

- The Origins of Boys and Girls Bikes (1890s)

- Women and Exclusion from Long Distance Running (1896-1984; pictured)

- Vintage Women’s Basketball Teams (1900s)

- Opportunity and Athletic Performance (1900s-2000s)

- Changing Biology: Age at First Menstruation (1840-2000)

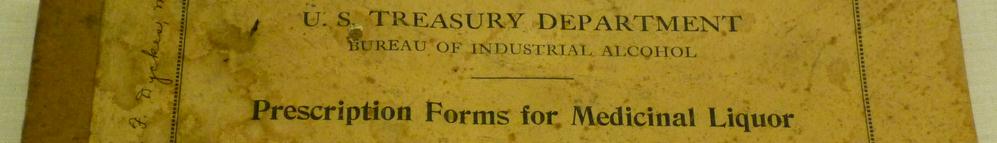

- Prohibition and Medicinal Alcohol (1919-1933; pictured)

- Social Hygiene and the Gender of Health (1922)

- Hysteria, the Wandering Uterus, and the “Vaginal Massage” (1930s)

- VD and the Virgin/Whore Dichotomy in WWII Propaganda (1940s)

- Personifying Danger: Women as Vectors of STDS (1940s)

- The Pill and the Invention of the Monthly Cycle (1960s-2000s)

- Male and Female Victims of “Intimate” Homicide (1976-2004)

Fashion and Norms of Attractiveness:

- From Manly to Sexy: The History of the High Heel (1600s, 2000s)

- Ankle Porn and Knee-Gasms: Making Sewing Sexy (1900s-1920s)

- A Historical Look at Bodies as Fashion (1900s-2000s)

- Women Wears Men’s Clothes to a Prize Fight; World Gasps (1910)

- Two Facts about Figure Skating Fashion (1920s-1930s, 1980s)

- The Feminine Ideal (1928; pictured)

- Plastic Surgery Ad (1936)

- Vintage Posters of African American Hair Products (1939)

- Putting Glamour in its Proper Wartime Place (1940s)

- “Are You Popular?”: An Educational Film (1947)

- 1950s Beauty Pageant Judging Guidelines (1959)

- Dressing Ourselves: Gendered vs. Unisex Pants (1960s-’70s)

- Regulating Black Women’s Hair (1969)

- Changing Fashion Standards: Sexy Shoes (1969)

- Gender Neutral Ruffles (1970s)

- Nipples and the Presentation of Femininity (1970s-2000s)

- Model on Cover of Elle has a Real Face (1986)

- A Historical Look at Changes in Work Type (1850-2000)

- Men Need Women’s Jobs to Avoid Being Bums (1934)

- Modern Appliance Girls (1936)

- World War II Era Chest Protector (1939)

- High-Tech Rosies in World War II (1940s; pictured)

- Myth Making and the “We Can Do It” Poster (1940s)

- The Changing Workplace: Caring for Female Workers (1940s)

- Women Soldiers During World War II (1940s)

- Guide to Hiring Women (1943)

- Vintage PSA for the Equal Pay Act… featuring BatGirl (1963)

- A List of Reasons Not to Hire Women (1963)

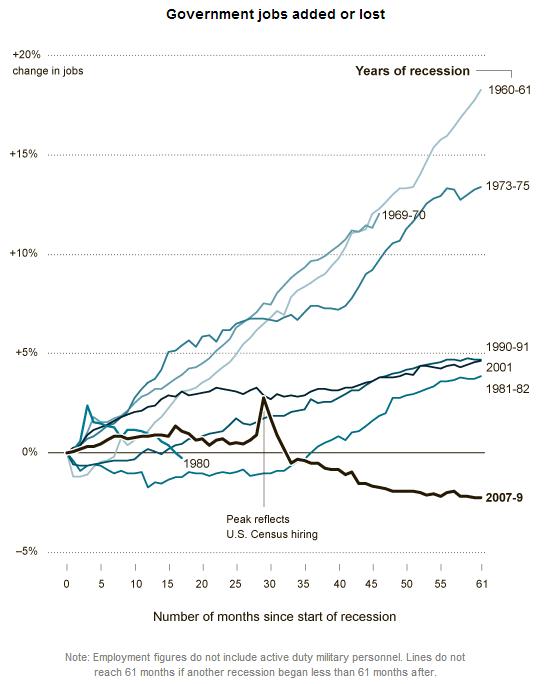

- Gender, the U.S. Workforce, and the Recession (1965-2005)

- Futurists Imagine the 21st Century (1967)

- “Don’t Call Me a Cowgirl!” (1969)

- Sexism in Aviation: Then and Now (1970s, 2000s)

- Job Segregation by Sex (1972-2008)

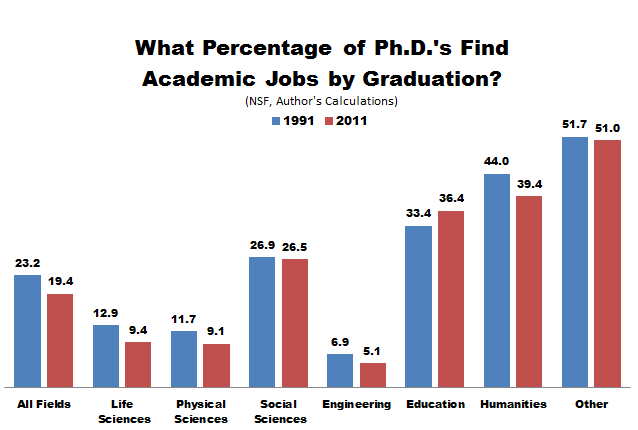

- Gender and Changes in the U.S. Occupational Profile (1972-2012)

- Kitchen and Maid Spanish (1976, 1978)

- Was “Cathy” a Feminist Heroine? (1976-2010)

- More Men and Fewer Women Earning Poverty Wages (1979, 2007)

- Women Cook, Men are Chefs (1980s)

Education:

- Women Now Graduating at Higher Rates than Men (1880s-1970s)

- Replacing Women: Slaves, Servants, and Technologies (1800s, 1940s)

- Miscegenation Ball Anti-Lincoln Cartoon (1864)

- The Two Paths: Good Mothers and Outcast Sluts (early 1900s; pictured)

- Why Did Married Mothers Go to Work? (1900-2002)

- Medicalizing Gendered Marriage (1939)

- Visions of the Future of Housework (1950s)

- Are More Women Marrying Younger Men? (1960-2007)

- Marriage Trends and Why I’m Not Married (1960-2010)

- Class Privilege and Parental Leave (1961-2008)

- “When You Marry”: A Textbook (1962)

- Of Housework and Husbands (1965-1995)

- Ritalin for Moms (1967)

- The Invention of the Playboy (1969)

- Women, Education, and Trends in Childlessness (1976-2008)

Suffrage:

- Vintage Anti-Suffragist Postcards (1900s)

- Facets of the Woman’s Suffrage Movement (1900s)

- How Suffragist Postcards Got Out the Vote (1910s)

- Delay Thanksgiving Dinners to See Suffragettes (1909)

- Against Giving Women the Right to Vote in Massachussetts (1915)

- Celebrating Women’s Suffrage (1919)

- Early Appropriation of the Women’s Movement in Advertising (1910)

- Anxiety about “Objectionable Hair”: Introducing Armpit Shaving (1915, 1934)

- Framing Tampon Use (1940s)

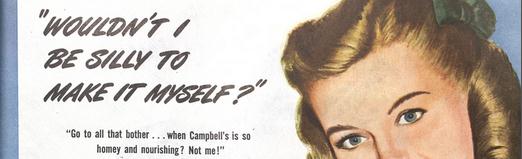

- Marketing Pre-Made, Non-Perishable Food (1940s; pictured)

- “For Men Only”: Vintage Campbell’s Soup Ad (1940s)

- Ad Shows Husband as Primary Caretaker (1947)

- Jell-O to the Rescue (1950s)

- More Leisure through Technology (1950s, 1970s, 2000s)

- Honda Fits She’s and the Dodge LaFemme: History Repeating Itself (1950s, 2000s)

- “The Orchid of Beer”: Beer for Women (1953)

- Changing Midol Ads (1960s, 1990s, 2000s)

- “Treat Your Rifle Like a Lady” (1968)

- “You’ve Got Your Own Cigarette Now, Baby” (1969)

- Mocking Feminism in a Smirnoff Ad (1970s)

- Appropriation of the Women’s Movement (1971)

- Contrasting Stereotypes of Mexican Men and Women (1975)

- Virginia Slims Ads (1978)

- Awesome Vintage LEGO Ad (1981)

- More Gender-Neutral LEGO Ads (1982)

- Marketing the Tampon: “Will I Still Be a Virgin?” (1990s)

- Historical Perspective on the LEGO Gender Gap: Part I (1932-1988; pictured)

- Encouraging Girls to Identify with Barbie (1959)

- Bob Barker Harasses Little Girls on The Price is Right (1970s)

- “Particularly with the Boy”: Worries about Feminization of Boys (1974)

- Historical Perspective on the LEGO Gender Gap: Part II (1989-2003)

- Historical Perspective on the LEGO Gender Gap: Part III (2004-2011)

- Historical Perspective on the LEGO Gender Gap: Part IV (2012)

War and Military:

- War as Sexual Domination (1957)

- Recruiting Women Marines (1970s-2000s)

Activism:

- Wimbledon Cartoon Imagines Progress for Women (1927)

- Appropriating Social Movements in Playboy (1960s-1970s)

- Gender Politics in Life and Time (1971, 1977)

Color, Sound,and Language:

- Men in Pink: Two Velasquez Paintings (1650s)

- Gender and the Social Construction of Sound (1906-2006)

- Changes in Gendered Language Over Time (1930-2005)

- The History of Pink and Blue (1960s)

Just for Fun:

- The Story of the Shopping Cart (1937-2000s)

- Urinals for Women: An Alternative Reality (1953)

- Constructing a Shocking (Falsely) Sexist Past (1955, but not really)

- Disney Futurists Imagine 2010 (1958)

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.