Are sounds gendered? Yes. Does the gender of sounds change over time?

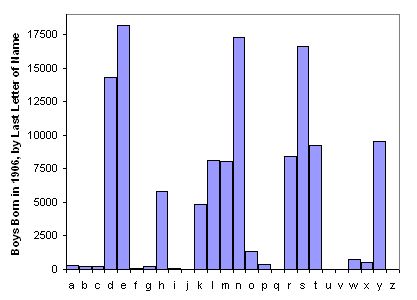

From the surprisingly interesting blog of Laura Wattenberg comes these graphs showing that popular masculine endings to names has changed over time.

1906:

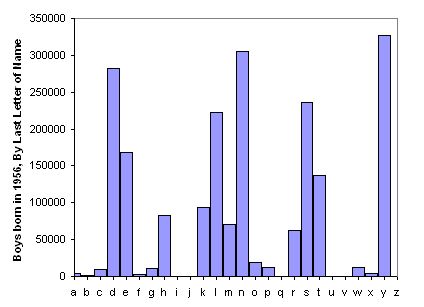

1956:

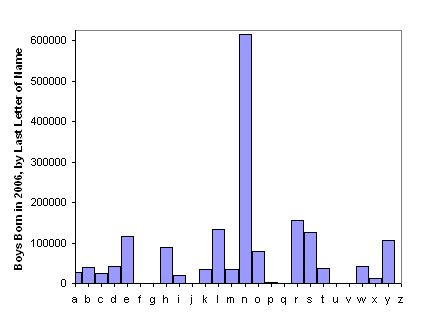

No dramatic changes from 1906 to 1956, but then, in 2006, n is triumphant!

2006:

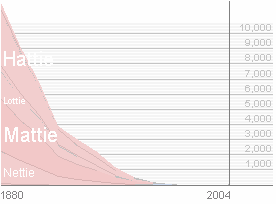

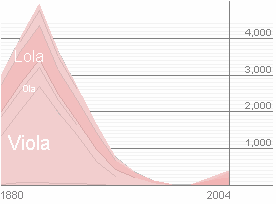

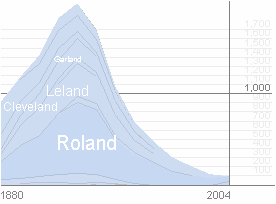

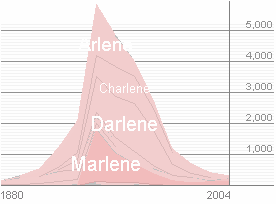

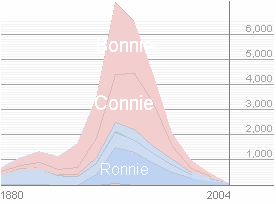

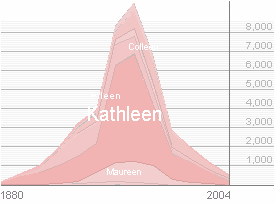

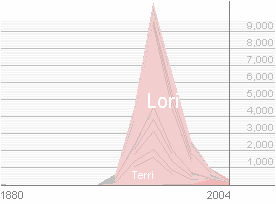

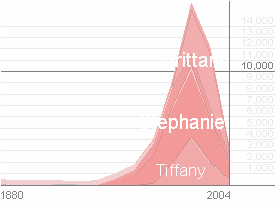

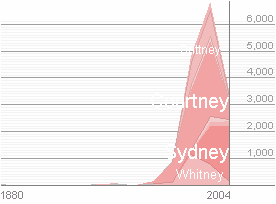

Laura also offers some data showing how boy and girl name endings have shifted since the 1880s:

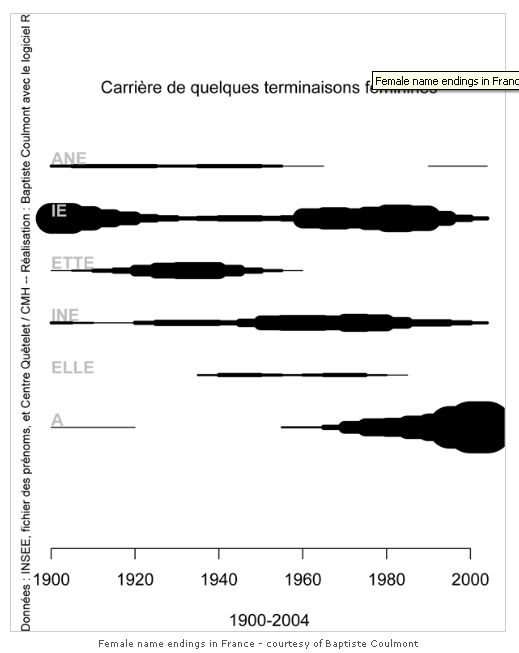

This figure, relatedly, shows trends in the endings of girl babies’ names in France:

Graphs from here, here, and here. Hat tip to Montclair Socioblog.

UPDATE: In the comment thread, Sator Arepo notes:

Sounds are not equal to letters. The graphs are misleading in that they (with exception of the French language spectrograph-like pictures) they equate the sound of the end of the name with the appearance of the letter in the written word.

Commenter pfctdayelise notes something similar, above. However, it’s even more misleading in the tables, and would depend widely on the origin of a name whether and how certain letters were pronounced.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

Comments 7

pfctdayelise — June 20, 2009

*Names* are gendered, and change over time, but we knew that. I think it's a bit of leap to say that *sounds* are gendered.

Trabb's Boy — June 20, 2009

There was something in (I think) Stephen Pinker's latest book about this, though that was the beginnings of names. He was speaking about it as a general fashion trend thing, with the cutting edge types doing something unusual, and the masses gradually following until the cutting edge types decide to do something different.

My apologies if this wasn't Pinker. Since I started mostly listening to downloaded books instead of reading them, I have trouble remembering what information came from what book.

thewhatifgirl — June 21, 2009

pfctdayelise, sounds are most certainly gendered (though I don't think picking mostly common names helps illustrate that). My real first name is unusual and ends with an 'n'. I've met three other women and one man with the same name, and most people express shock when I tell them that I knew a man with the same name. Yet when it's read off of a sheet of paper, I get male pronouns. If it ended with an 'ah' sound or an 'ee' sound, I bet no one would hesitate to use female pronouns.

Blue Wizard — June 22, 2009

@ Trabb's Boy

I believe you're referencing Steven Levitt's Freakonomics, where he devotes a chapter to talking about how names move from higher to lower socioeconomic classes – when name becomes common in lower class, the upper class abandons those names and finds new ones.

Original Will — June 22, 2009

It would be interesting to see this broken out by socioeconomic class and by ethnic group. At least among the circles I'm familiar with, it seems like there are zillions of boy children being named Braden, Jaden, Caden, etc.

No offense to anyone, but I can't wait for this particular fad to run out.

Sator Arepo — June 27, 2009

Sounds are not equal to letters. The graphs are misleading in that they (with exception of the French language spectrograph-like pictures) they equate the sound of the end of the name with the appearance of the letter in the written word.

Commenter pfctdayelise notes something similar, above. However, it's even more misleading in the tables, and would depend widely on the origin of a name whether and how certain letters were pronounced.

This does not invalidate the point, of course. We should merely be careful about our interpretation of the data.

Quick hit: the gender binary fractal in geekdom | Geek Feminism Blog — January 9, 2010

[...] gender binary–that is, the rule that everything (oh animals, jobs, food, kleenex, housework, sound, games, deordorant, love and sex, candy, vitamins, etc) gets split into male and female–is [...]