My best friend’s car has four cup holders in the front seat. FOUR. I would ask what a person does with four cup holders, except I’m too busy feeling jealous. I drive with a measly two.

Cup holders, or what the US News and World Report quaintly called “crannies for drinking cups” as late as 1989, weren’t considered an automotive necessity until the ’50s. That was when, reports Bon Appetit, “drive-ins and drive-thru windows became mainstays of American eating.” Before then, people were expected to stop for food and drink and then be sated. Can you imagine?

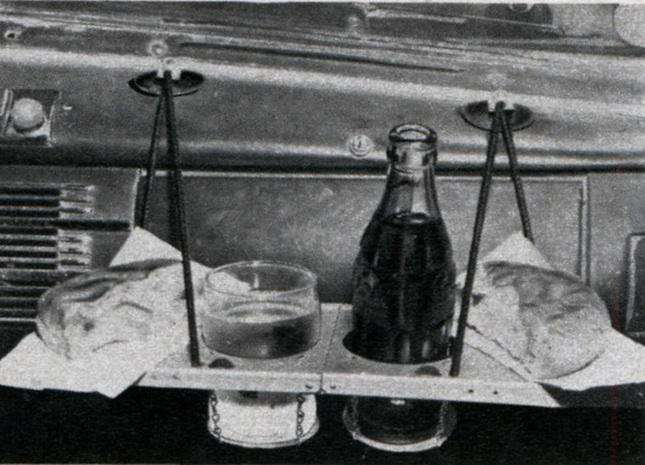

It took a long time, though, for the automobile industry to figure out exactly how to deliver us our cup holders. First there was a “snack tray for car,” as pictured in a 1950 newspaper ad:

Companies also sold between the seat inserts that held cups and Cadillac sold a limousine with magnetic cup holders:

The cup holder as we know it today came to us in 1983 alongside another innovation: the mini van. The first cup holders “sunk into the plastic of the dashboard” were installed in the Dodge Caravan and Plymouth Voyager. It would be a decade, though, before cup holders came standard in essentially every car.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.