The Minnesota law enforcement community turned out strong to honor the memory of Officer Joe Bergeron of Maplewood, killed in the line of duty on May 1. Of course, such deaths ripple outward to affect much broader communities. I recall my mother’s stories about a brave officer in our family — the nice cousin who sang Everly Brothers songs with her, I believe — shot and killed during a basic traffic stop. So I was especially troubled to see media reports citing a “a 17 percent jump in the number of officers ‘feloniously killed’ in the line of duty.”

The reports are based on an FBI press release, but is it really the case that More Officers Died in the Line of Fire in 2009? The National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund tracks law enforcement deaths by year and jurisdiction, while the Officer Down Memorial Page provides breakdowns by state. These include both felonious deaths (which are primarily firearms-related) and accidental deaths (which are primarily traffic-related). The long-term trend in officer deaths is shown in the first figure below. You can see peaks of 285 deaths in 1930, 279 in 1974, and 240 in 2001, but a decline to 116 officer deaths in 2009.

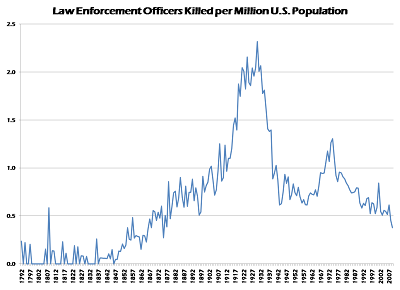

Of course, there were a lot more people in the United States in 2009 than in 1974, and a lot more in 1974 than in 1792. To get a better sense of long-term trends in the rate of law enforcement deaths, I plotted this long NLEOMF data series after standardizing it by population. The figure below shows the resulting rate of law enforcement deaths per million citizens.

Death rates were highest during the prohibition era from 1920-1932, reaching a peak rate of 2.32 officers per million population in 1930. Officer deaths then dropped dramatically in the 1940s and 1950s before rising again to a second peak of about 1.3 deaths per million in 1974. Since then, there has been another steep decline that extends to the present. By my calculations, the 2009 death rate of .38 per million has now reached its lowest point since 1875.

Death rates were highest during the prohibition era from 1920-1932, reaching a peak rate of 2.32 officers per million population in 1930. Officer deaths then dropped dramatically in the 1940s and 1950s before rising again to a second peak of about 1.3 deaths per million in 1974. Since then, there has been another steep decline that extends to the present. By my calculations, the 2009 death rate of .38 per million has now reached its lowest point since 1875.

While there were indeed 7 more felonious deaths in 2009 than in 2008, I can find no evidence of a longer-term increase in the rate, number, or proportion of felonious deaths. According to an NLEOMF research bulletin, about 62 percent of officer deaths were felonious in the 1970s, about 54 percent were felonious in the 1980s, and about 46 percent were felonious in the 2000s.

A few caveats on this analysis: I cannot vouch for the quality of the National Law Enforcement Memorial Fund data in the early years of this series, but it seems to track the FBI data very closely for more recent years. One might also critique the latter figure for using the total population as the denominator rather than the number of law enforcement officers.

Finally, it should go without saying that 116 officer deaths remains far too many. Nevertheless, this picture is far more heartening than the one painted by recent news reports — the rate of officer deaths appears to be lower today than it has been for the past 135 years.