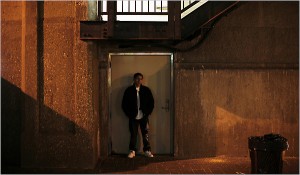

I spent eight hours with our state’s parole board yesterday. I sat in on two “Murder Review” hearings, the stated purpose of which is to: “determine whether or not the inmate is likely to be rehabilitated within a reasonable period of time so that the offender’s sentence may be converted to life with the possibility of parole, post-prison supervision, or work release.”

The individuals in both of these cases were charged with aggravated murder; for both of them the question was whether they could prove themselves “rehabilitatable” so that they might have the possibility of parole at a future date. One has at least 9 more years to serve on the mandatory part of his sentence before he can even be considered for release; the other is nearly 70 years old and is hoping for a chance to re-connect with family on the outside rather than die in prison.

The circumstance of the cases were quite different, and so were the hearings. I’ll focus on the first, though, because it raises some difficult moral, ethical, and behavioral questions. The first man presented over 100 pages of records, proof, and testimony that he has worked hard in his 20-years in prison to change and grow. He has “programmed” persistently and thoroughly, participating in many educational and cognitive courses and experiences over the years. His crime was a truly horrifying case of domestic violence – there really is no excuse for that crime and no making up for it, and the man acknowledges that. Members of the victim’s family came to testify at the hearing, and their grief and pain was readily apparent. They fear his possible release 10 or more years in the future, and they hope that he will serve natural life in prison. The district attorney who attended the hearing called this man “a monster” and also asked that he be found “not likely to be rehabilitated in a reasonable amount of time.”

I was very impressed with the members of the parole board. They had clearly done their homework in preparing for the hearings, and they patiently listened to testimony and took notes for the 8+ hours of these hearings, not even taking a break for lunch. After the testimony of the inmates and their attorneys, they asked careful, thoughtful, and very probing questions, pushing the inmates to look deeper within themselves to answer the difficult questions. Being a member of the parole board must be a thankless job – I doubt they get much credit for giving second (or third, or fourth) chances, but they undoubtedly face a great deal of public scrutiny and criticism should a release decision turn out badly.

The decisions will come later after the parole board has time to review and reflect on the evidence presented. But here is the question: how can and should we judge change? Even if an inmate has turned his life around in prison, does he deserve another chance at life in the community? He can’t change the circumstances of his crime, but if he really has changed himself, is that enough? Should it be? How much weight should the victims’ fear, grief, and pain hold in parole decisions? Can we ever really know if an inmate is “rehabilitated” enough or if he is just a master manipulator as the victims and prosecutors believe and claim? Is it worth the risk to grant even the possibility of parole?

Big questions. I don’t have any clear answers at this point, but I definitely came away from the hearings with a lot to think about…

As I sit here listening to election results on the west coast, I’m reminded that it is both privilege and a responsibility to vote. I didn’t always feel that way – as a working class kid, I was never really convinced that my vote “counted”. I’m still not sure one vote makes a significant difference, but I do know that I owe it to my incarcerated students to vote knowledgeably and responsibly on issues that concern us all. And I owe it to my on-campus students to set an example of civic responsibility.

As I sit here listening to election results on the west coast, I’m reminded that it is both privilege and a responsibility to vote. I didn’t always feel that way – as a working class kid, I was never really convinced that my vote “counted”. I’m still not sure one vote makes a significant difference, but I do know that I owe it to my incarcerated students to vote knowledgeably and responsibly on issues that concern us all. And I owe it to my on-campus students to set an example of civic responsibility.

So, I have been following the case of

So, I have been following the case of  Sad news from my hometown area –

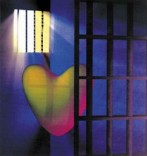

Sad news from my hometown area – The Marion County Jail in Salem, Oregon is instituting a new policy on January 1st that will

The Marion County Jail in Salem, Oregon is instituting a new policy on January 1st that will