Two different stories hit the news (features) this week, and I was struck by the similar themes in these bad-boy-grows-up-in-prison-and-tries-to-go-straight-on-the-outside stories. The first, published in The Oregonian, focuses on LaMarcus Branch, an ex-Crip who was recently released from prison and is now making visible efforts to reach young gang members in Portland. He and friends wear matching t-shirts branding them the new, self-imposed label of BRO (Brothers Reaching Out), and they “show up at gang funerals and high school football games to ease tensions, they mentor young men on parole, and they try to intervene in gang scuffles before things turn violent.”

Two different stories hit the news (features) this week, and I was struck by the similar themes in these bad-boy-grows-up-in-prison-and-tries-to-go-straight-on-the-outside stories. The first, published in The Oregonian, focuses on LaMarcus Branch, an ex-Crip who was recently released from prison and is now making visible efforts to reach young gang members in Portland. He and friends wear matching t-shirts branding them the new, self-imposed label of BRO (Brothers Reaching Out), and they “show up at gang funerals and high school football games to ease tensions, they mentor young men on parole, and they try to intervene in gang scuffles before things turn violent.”

Branch claims that his time in prison saved his life. While that itself is perhaps not that unusual, what is unique about Branch is that he is particularly grateful for his lengthy sentence. The article explains:

Branch, at 24, was sent to prison for 13 years, four months, a rare consecutive sentence for first-degree robbery and second-degree assault, his first Measure 11 offenses. During his first decade behind bars, he was angry and bitter, often in trouble for fights or gang beefs. But the last few years of his sentence brought a change of heart.

“I’d say those extra three or four years was the most important part,” he said. “They gave me time to realize the life that I lived wasn’t a life.”

Measure 11 is our version of mandatory minimum sentencing in Oregon, and I generally hear complaints about the harshness and inflexibility of such sentences. This is one of the only times I can remember hearing a former inmate say he appreciated the extra years he served. Branch even sent a letter to the prosecutor – now a judge – who won the case against him, saying if he had done only 70 or 90 months in prison, he probably would have returned home bitter and angry and jumped right back into gang life. “So I’m not just thanking you for winning the case, but also for getting me this 160 months, because now I see and realize with understanding that there’s more to life than gangs and crime.”

Branch has only been out of prison since March, and he still does not have a driver’s license or a job. He will face significant hurdles in building a new life and following his dream to mentor youth. But the choices are his.

The second story, published in the New York Times, focuses on 26-year-old Raheem Watson, who spent nearly ten years of his life in juvenile corrections and prison. As difficult as his time in prison was, Watson, too, believes he underwent a transformation during his incarceration and he claims he came out of prison this February as “a mature adult.” Watson doesn’t have a driver’s license or a job yet, either, but he is working toward both and he shares Branch’s passion to mentor young people.

Watson had a difficult childhood, abandoned by his father at age 4 and raised by a drug-dealing mother who died after ingesting cocaine laced with rat poison when he was 12. The piece of Watson’s story that I most appreciated was the moment when social context met individual responsibility head-on. The article explains:

Mr. Watson said he sometimes felt the troubles he had faced were a product of fate — a notion that seemed at odds with his stated desire to steer others away from the path he took.

So, the question again: Did he have a choice? He rolled it around in his head, struggling with its implications.

“Yeah,” Mr. Watson said. “I had a choice.”

Yes, Branch and Watson both had choices. They may not have had great options, but they made the choices that sent them each to prison. And now they face hard choices again every day. Criminologists know all too well the difficulty ex-felons have reintegrating into the community, finding jobs, and creating new lives for themselves. The struggle and the stigma are real and can be overwhelming. But making the hard choices and “doing good” is truly the best way these men can fulfill their goals of mentoring young people. In leading by example, they may be able to help influence the next generation to make better choices.

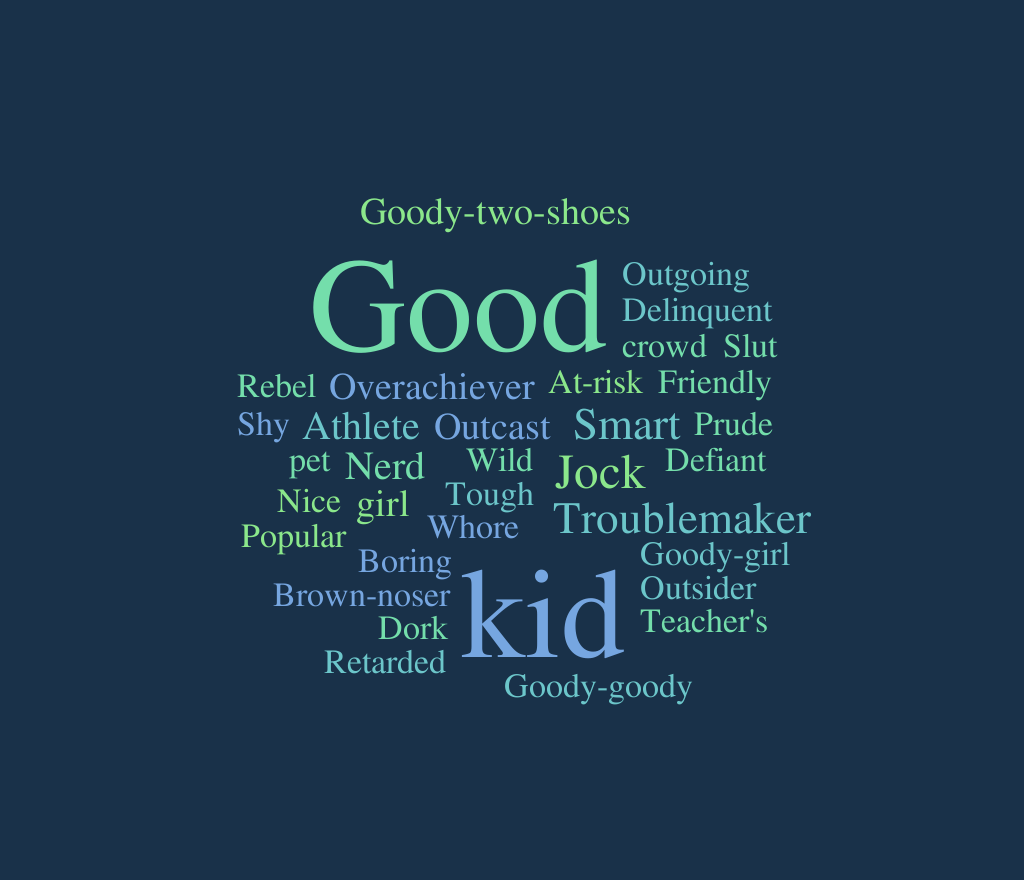

I asked my Juvenile Delinquency students to write short essays reflecting on the labels that had been applied to them as they were growing up. As I read the essays, I took note of the words they used to explain how other people saw and described them, and I created the word cloud above (worditout.com) .

I asked my Juvenile Delinquency students to write short essays reflecting on the labels that had been applied to them as they were growing up. As I read the essays, I took note of the words they used to explain how other people saw and described them, and I created the word cloud above (worditout.com) .