For frequent readers of this blog, you’ve probably read several posts in which I discuss the anti-minority, anti-immigrant White backlash phenomenon. For those who aren’t familiar with such arguments, the White backlash is basically the idea that many (as in a large number, perhaps even most, but not all) White Americans increasingly feel destabilized and even threatened by many of the following developments in American society:

- The changing demographics of the U.S. in which non-Whites increasingly make up a larger proportion of the population and the projection that in about 35 years, Whites will no longer be a majority in the U.S.

- The political emergence of non-Whites, best represented by the election of President Obama, and also illustrated by the growing Latino population.

- The continuing evolution and consequences of globalization, the growing interconnections between the economies of the U.S. with other countries, and the economic rise of China and India.

- The “normalization” of economic instability and how, even after this current recession ends, Americans will likely still be vulnerable to economic fluctuations that affect the housing market, stock market, and overall unemployment.

- The unease about the U.S.’s eroding influence and military vitality around the world.

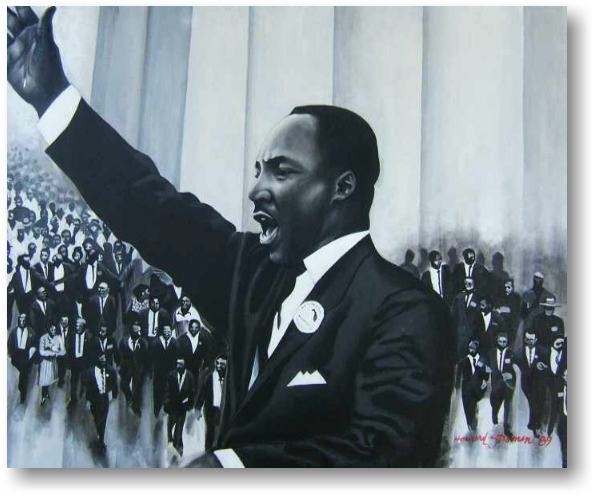

Taken together, these institutional developments and their negative consequences have been increasingly been felt on the individual level by many Americans. But in the case of White Americans, they have had a particularly significant impact because, as a group, their position at the top of the American racial hierarchy is increasingly being threatened — politically, economically, and socially.

That is, even though many Whites will deny their position at the top and the privileges that they directly and indirectly enjoy, ultimately very few would be willing to trade places with a person of color if given the choice. So as many Whites see these shifts and changes taking place around them, they increasingly feel confused, defensive, and angry about what is happening to “their country.”

For those who say I’m overreacting, take a look at Gregory Rodriguez’s recent article in Time magazine where he basically points out the same thing:

As much as Americans pride themselves on the notion that their national identity is premised on a set of ideals rather than a single race, ethnicity or religion, we all know that for most of our history, white supremacy was the law of the land.

In every naturalization act from 1790 to 1952, Congress included language stating that the aspiring citizen should be a “white person.” And not surprisingly, despite the extraordinary progress of the past 50 years, the sense of white proprietorship — “this is our country and our culture” — still has not been completely eradicated. . .

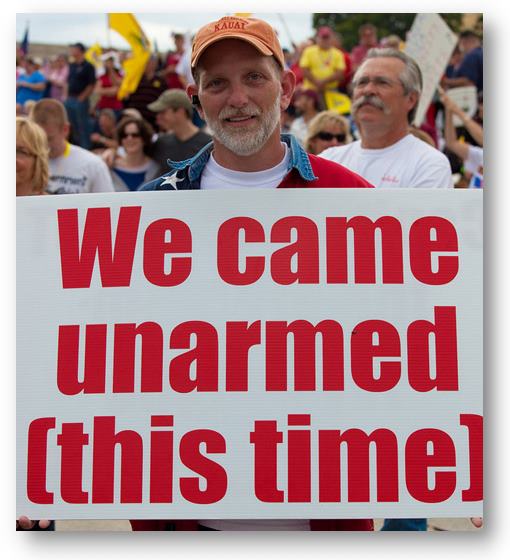

This [White backlash] won’t take the form of a chest-thumping brand of white supremacy. Instead, we are likely to see the rise of a more defensive, aggrieved sense of white victimhood. . . . one can hear evidence of white grievance in many corners of the country. And it’s not coming just from fringe bloggers.

In the spring of 2008, candidate Hillary Clinton appealed to “hardworking white Americans” to help her campaign against an ascendant Barack Obama. Last March, conservative commentator Glenn Beck suggested that the white man responsible for the worst workplace massacre in Alabama history was “pushed to the wall” because he felt “silenced” and “disenfranchised” by “political correctness.” . . .

[E]ven though they are still the majority and collectively maintain more access to wealth and political influence than other groups, whites are acting more and more like an aggrieved minority.

Columnist Frank Rich at the New York Times makes similar points:

The conjunction of a black president and a female speaker of the House — topped off by a wise Latina on the Supreme Court and a powerful gay Congressional committee chairman — would sow fears of disenfranchisement among a dwindling and threatened minority in the country no matter what policies were in play. It’s not happenstance that Frank, Lewis and Cleaver [African American members of Congress] — none of them major Democratic players in the health care push — received a major share of last weekend’s abuse.

When you hear demonstrators chant the slogan “Take our country back!,” these are the people they want to take the country back from. They can’t. Demographics are avatars of a change bigger than any bill contemplated by Obama or Congress.

The week before the health care vote, The Times reported that births to Asian, black and Hispanic women accounted for 48 percent of all births in America in the 12 months ending in July 2008. By 2012, the next presidential election year, non-Hispanic white births will be in the minority. The Tea Party movement is virtually all white. The Republicans haven’t had a single African-American in the Senate or the House since 2003 and have had only three in total since 1935. Their anxieties about a rapidly changing America are well-grounded.

As others, including many of my fellow sociologists, have already written about, we can see examples of this White backlash throughout American society, such as the growing militancy of Tea Party members, the Texas school board elections, and the recent racial incidents and tensions at the University of California campuses, to name just a few of the most recent examples.

I anticipate that there will be plenty to say and write about in terms of this growing White backlash movement for the foreseeable future, so for now, I will leave it at that and just say that whether White Americans like it or not, and whether they want to recognize it or not, this backlash among many White Americans is real and it is absolutely centered on racial issues, conscious and unconscious.