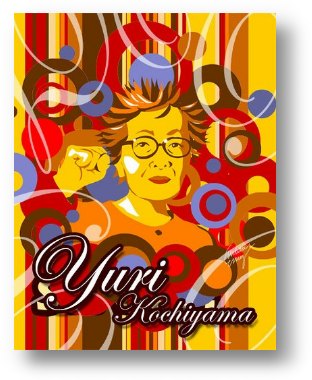

You may have heard that long-time civil rights activist and Asian American icon Yuri Kochiyama passed away earlier this week at the age of 93. Readers can learn more details about her amazing life through boted Asian American scholar Diana Fujino’s biography Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama. Prominent Asian American blog Reappropriate also has links to several other articles from major media outlets about her passing.

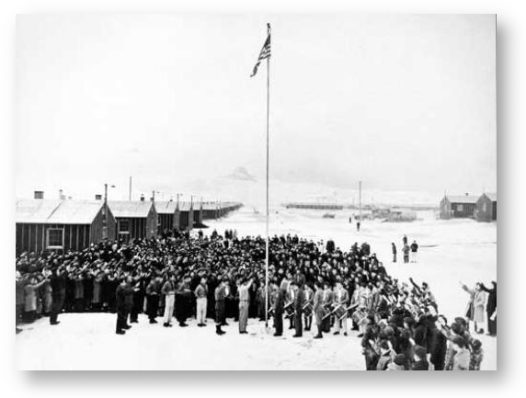

The biography and articles highlight how she grew up in the Los Angeles area and had a seemingly normal middle-class life. All of that changed after the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. As history records, this eventually resulted in 120,000 Japanese Americans (two-thirds of them being U.S. citizens) having their constitutional rights revoked and incarcerated, just based on their Japanese ancestry, in dozens of prison camps across the U.S., without any due process whatsoever.

Among those imprisoned were Yuri and her family and this experience forever changed her perspective on the state of race relations, racism, and the overwhelming need for social justice in the U.S. She eventually married a Japanese American GI and moved to Harlem, New York City. There, she befriended a young Black nationalist named Malcolm X and in the course of her friendship, galvanized her determination to work toward social equality and justice on behalf of her community. She was there when Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965.

Thereafter, she became known for actively participating in the movements for ending the Viet Nam War, Puerto Rican independence (highlighted by being part of the group that occupied the Statue of Liberty in 1977), and for Japanese American reparations. In her later years in Oakland, CA, she kept up her activism and social justice work, particularly around the fight against racial profiling and rounding up of Arab and Muslim Americans in the aftermath of 9/11, as detailed in the excellent documentary “Lest We Forget” that highlighted the similarities between Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor and Arab & Muslim Americans after 9/11. Here at my institution, the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, our Asian American student center is named the “Yuri Kochiyama Cultural Center” on her behalf.

For me personally, Yuri Kochiyama was a hero and an inspiration. Like Yuri, I grew up in a predominantly White community and was entrenched in an assimilationist environment. I did not care about my roots as an Asian American, an immigrant, or a person of color — I just wanted to fit in and be like everybody else around me. In doing so, I was ignorant of all the racial injustices that had been perpetrated against people like me throughout U.S. and world history and that was still taking place all around me in different ways.

It wasn’t until my later years in college and after I started studying Sociology and Asian American Studies that I finally woke up, opened my eyes, reclaimed my identity, and pledged myself to do what I could to fight for racial equality and justice. That’s when I first learned about Yuri Kochiyama. She represented not just someone who was determined to draw on her personal experiences of racism to fight on behalf of others in similar situations, but as an Asian American woman, she stood in stark contrast to the stereotypical images of Asian American women as meek, submissive, exotic, and hypersexualized “geishas” and “China dolls.”

In other words, she gave all of us — men and women, Asian American or not — a different example of what Asian Americans, particularly women, are capable of. It is these examples and memories of Yuri Kochiyama as a strong, determined, committed, and inclusive activist and Asian American woman that I will carry forth with me.