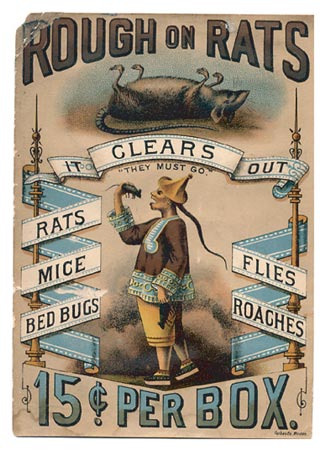

My fellow sociologist blogger Joe Feagin at Racism Review mentions that David Segal over at Slate has a very interesting and informative slideshow of racist commercial caricatures over the years. For those who are too young to remember, blatantly derogatory and stereotypical images of Blacks, Latinos, Native American Indians, and Asians were routinely used to sell products not too long ago. Below is just one example:

Nasty stereotypes have helped move the merchandise for more than a century, and the history of their use and abuse offers a weird and telling glimpse of race relations in this country. Not surprisingly, the earliest instances were the most egregious.

This circa-1900 ad for a rodent-control product called “Rough on Rats” doesn’t just exploit the then-popular urban legend that Chinese people eat rats. It also underscores the intensity of American xenophobia of the day. There were anti-Chinese riots at the time, as well as legislation like the Chinese Exclusion Act, a federal ban on immigration passed in 1882. (It was on the books until 1943.) In the ad, “They must go” refers both to the rodents and the Chinese.

For those interested in the sociology of media and cultural images, my colleagues at Contexts magazine host a very interesting blog titled “Sociological Images” that you should definitely check out.

Unfortunately, as the Slate slideshow and captions point out, there are a few racist caricatures that are still with us today and you may be surprised at what they are.