Last week, the U.S. commemorated the 70th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese military that led to the U.S.’s entry into World War II. Of course, the attack was a watershed moment in U.S. history — Japan’s unjustified and heinous act led to the deaths of 3,000 human beings, united the U.S. like never before, and in the end, was the start of Japan’s downfall as a imperial military power.

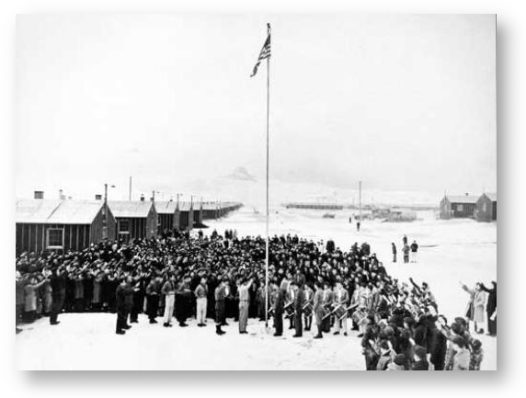

Unfortunately, the Pearl Harbor attacks also prompted the U.S. government to strip 120,000 Japanese Americans of their legal rights and imprison them without any due process, based largely on the “fear” that Japanese Americans would be loyal to Japan and engage in espionage or treason against their adopted U.S. homeland.

This entire “internment” episode has been recounted and analyzed over the years, most notably by the bipartisan Congressional “Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians,” which ultimately conducted a thorough investigation and in their final report titled “Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians,” finally concluded that the imprisonment of Japanese Americans during World War II was a “grave injustice” and resulted from “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” Congress then approved and distributed a reparation payment of $20,000 to all surviving Japanese Americans who were imprisoned. To my knowledge, this is the only instance in which the U.S. government has officially apologized and provided monetary reparations to any of the injustices that they’ve committed in its history.

As it turns out, this week’s anniversary commemoration unfortunately prompted some to once again bring up the old argument that there was a logical rationale to the U.S.’s imprisonment of Japanese Americans, or that it was even completely justified. For example, in a museum review of Heart Mountain Interpretive Center (in Wyoming, site of one of the prison camps) in the Dec. 9, 2011 edition of the New York Times, ‘art critic’ Edward Rothstein engages in such musings.

Specifically, Rothstein uses a few historical examples of misdeeds by Japanese and Japanese Americans to argue that “the threat was palpable” and that therefore, there was a “rationale” for the U.S.’s subsequent imprisonment of 120,000 Japanese Americans. While Rothstein does state, “I am not suggesting that such factors justified the relocations,” the tone of his piece displays an ignorant accounting of the entire collection of historical facts surrounding how isolated incidents of Japanese and Japanese Americans misdeeds were exaggerated and generalized to an entire population, how many allegations of espionage and sabotage by Japanese Americans were never substantiated and even completely fabricated, and how similar and even more pernicious acts by Germans and German Americans were largely ignored.

Unfortunately, Rothstein’s piece is a sad example of selective memory, if not outright revisionist history. The examples he cited as providing “rationale” for the mass imprisonment are of dubious historical accuracy and value and even if valid, only reinforce and perpetuate the tired notion that the acts of a few can be taken out of context and generalized to an entire population. In response to Rothstein, I would like to share the responses of some of my colleagues who provide a more clear and comprehensive picture of the supposed “palpable” threat of Japanese Americans after the Pearl Harbor attacks:

In his attempt to understand the wartime removal of Japanese Americans, Edward Rothstein (“the How of Internment, but not all the Whys”, NYT, December 9) repeats a set of falsehoods and distortions about its causes. He insists that because Japan engaged in widespread espionage, and decoded Japanese messages (in reality a mere handful) spoke of contacts, surely Japanese Americans were implicated in espionage. In fact, Tokyo’s spymasters shied away from using Americans of Japanese ancestry, whose loyalty to Japan they rightly suspected, and made use of non-Japanese. Col. Kenneth Ringle, the prewar agent of the Office of Naval Information who broke the most important Japanese spy ring in Los Angeles and was in a position to know the facts, was an outspoken defender of the loyalty of Japanese Americans.

Similarly, Rothstein declares that the Japanese “threat was palpable” since a Japanese submarine had sunk American shops and shelled a California oil field. In fact, only a single American ship was sunk, compared to the hundreds sunk by German submarines off the East Coast, and the single shelling incident took place after the order to remove Japanese Americans had already been issued. Worse, Rothstein argues that the “treasonous” conduct of a Nisei couple in Hawaii validated the fears of government authorities about West Coast Japanese Americans. The absurdity of this statement is easily demonstrated by the fact that there was no mass roundup of the large Japanese community in Hawaii itself.

Although he insists that he is not justifying removal, cultural critic Rothstein sadly displays not only a carelessness toward history, but reveals how much the baseless ideas about “Japanese” disloyalty that led to mass removal still remain in the culture.

Greg Robinson

Associate Professor of History

Université du Québec a Montréal

I write this disappointed letter in response to Edward Rothstein’s December 9, 2011 piece, “The How of an Internment, but Not All the Whys.” Notwithstanding the express reason for this piece (as a review), I was particularly struck by Mr. Rothstein’s incomplete and incendiary reading of not only U.S. history but Japanese American history. Dismissing the “now standard” evaluation of the internment as the “result of wartime hysteria and racism,” Mr. Rothstein offers an allegedly “clearer understanding of the prewar Japanese-American population” rooted in familiar characterizations of yellow peril takeovers, perpetual foreign frames, and traitorous subjects. What is especially remarkable and distressing is that Mr. Rothstein manages – quite irresponsibly — to take NYT readers “back in time” to aforementioned “wartime hysteria and racism.”

Cathy J. Schlund-Vials

Assistant Professor, English and Asian American Studies

University of Connecticut

I teach Asian American Studies to graduates of this city’s k-12 system, and I am continuously disheartened by the many young people who have never heard of Japanese American internment, or, if they have, possess no meaningful understanding of the nature of the event. With that lack of information in mind, I was appalled to see your paper repeat long since discredited misinformation in apparent disregard for rigorous scholarly work, and the trauma inflicted upon thousands upon thousands of individuals and families who did nothing but look like “the enemy.” Despite his assurance to the contrary, Edward Rothstein’s review of the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center implies that we should explore long since debunked (dare I say “fringe”) theories that justify the racial stereotype of Japanese Americans as inherently treasonous, and thereby make excuses for what scholars agree is a racially motivated and shameful event in U.S. civil rights history.

Jennifer Hayashida

Director, Asian American Studies Program

Hunter College, City University of New York

In Edward Rothstein’s review of the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center (“the How of Internment, but not all the Whys”, NYT, December 9) he declares that the unconstitutional incarceration of over 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry was “a geographic rationale, not simply a racial one.” Yet Mr. Rothstein fails to account for the fact that mass removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans did not occur at the site that propelled the U.S. into WWII—Hawaii. Indeed, all reputable scholars of the Japanese American Internment note that it was war time xenophobia and racism that spurred Executive Order 9066—an order that never specified ethnic ancestry and that effectively nullified the constitutional rights of every person living on the West Coast during WWII. FDR ordered the military to target Japanese Americans using EO9066. If that’s not a racial rationale, I’m not sure what is.

Jennifer Ho

Associate Professor

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Unfortunately, as a country, we are now poised to repeat the same mistake that was committed 70 years against Japanese Americans. Specifically, Congress is currently debating the National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2013. One of the proposed provisions is to give U.S. government authorities the ability to arrest and indefinitely detain anybody who they deem to be a threat to national security — including U.S. citizens — without charging them with a crime or giving them a trial. In other words, it would basically legalize what happened to Japanese Americans after the Pearl Harbor attacks.

Fortunately, there is opposition to these provisions from both sides of the political spectrum. If you also oppose these provisions, I urge you to contact your Representative and Senator and tell them to vote against these provisions. As George Santayana’s quote goes, “Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

This article originally published at Asian-Nation.org and is copyrighted © 2013