Earlier this year I wrote about an incident at Tufts University in which a drunk White student used racial slurs in harassing a group of Korean American students. As Inside Higher Education reports, Tufts is now dealing with a new controversy regarding its Asian American students, but this time it involves two groups of Asian Americans on opposite sides:

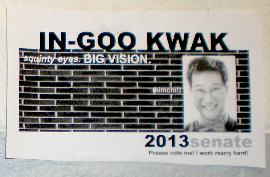

Two weeks ago, In-Goo Kwak, a freshman studying international relations and an immigrant from South Korea, put up a series of posters around his dormitory parodying the campaign poster of Alice Pang, another freshman of Asian descent who was running for the Tufts Community Union Senate. Kwak was not actually running for a student government position, but posted the parody next to Pang’s at the encouragement of his dorm mates. who thought he was right to poke fun at the air of political correctness he perceived on the campus.

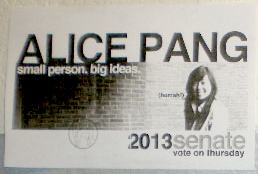

Pang’s poster included the campaign slogan, “small person, big ideas,” with the exclamation “hurrah!” next to her portrait. Kwak’s parody poster looks strikingly similar in design to Pang’s and includes the slogan “squinty eyes, big vision.” Next to Kwak’s portrait is the word “kimchi!” — a traditional Korean dish. Additionally, where Pang’s poster read “vote on Thursday,” Kwak’s said, “Prease vote me! I work reary hard!” in deliberately broken English. . . .

Linell Yugawa [Director of Tufts’ Asian American Center] sent an e-mail to the entire Tufts community denouncing Kwak’s parody. . . .

“Many Asian/Asian Americans and individuals of other racial backgrounds have been angered, hurt, and offended by these posters,” Yugawa wrote . . . “The posters not only mocked an authorized campaign poster, but used negative and racist stereotypes that correlate with the discrimination and dehumanization of Asians. These posters go beyond affecting one individual or group, but offend all who have an understanding of how racist stereotypes impact our lives.

“Some may argue that we need to ‘lighten up’ and/or ‘reclaim’ the stereotypes and words that have harmed us and our communities. While it is one thing to mutually engage in this type of conversation, it is another to post stereotypical and racist language that is open to interpretation and hurtful to many.”

There seems to be a few different issues here. According to Kwak (the student who put up the parody poster), the main issue here is freedom of speech and his right to criticize what he perceives to be political correctness gone overboard. My response is, yes he has the freedom to criticize what he perceives to be political correctness. But along with that, other students have the same freedom to denounce him as ignorant and I agree with those criticisms against Kwak.

It is a tricky situation in that yes, to a certain degree, one strategy for us as Asian Americans to fight back against the prejudice and discrimination that we’ve experienced through the years is to appropriate the stereotypes and reclaim the derogatory slurs that have been used against us and to turn them around for our own purposes. Other cultural minorities groups have been successful in doing this, such as Mexican Americans reclaiming the term “Chicano” and gay Americans reclaiming the term “queer.”

However, this does not mean that Asian Americans should start going around spouting stereotypes left and right. Such an effort to reclaim derogatory slurs needs to be focused, coordinated, and consensual. Unfortunately, Kwak’s effort in the form of his parody poster were none of those.

Instead, as Director Yugawa noted, his effort made fun of another Asian American student and used offensive stereotypes that rekindled very painful memories for many Asian Americans. Instead of uniting other Asian Americans as allies in the fight against anti-Asian racism, he alienated them.

The lesson here is that Asian Americans have a right to criticize what they believe to be political correctness and even to try to reclaim offensive historical caricatures. But in the process of doing so, if they use demeaning stereotypes against other Asian Americans, they should be prepared to accept the criticisms and denouncements that will inevitably follow. Ultimately, freedom of speech goes both ways.