At Oregon State University, our football team is big news. The team is 5-0 for the first time since 1939, and they are currently ranked as the eighth best team in the country.

At Oregon State University, our football team is big news. The team is 5-0 for the first time since 1939, and they are currently ranked as the eighth best team in the country.

What makes this particularly surprising and, frankly, glorious, is that the OSU football team only won three games total last season, and there were no great expectations for this year’s squad. OSU’s team is young and scrappy, and their confidence is growing with every win.

And, yes, I realize this is not a sports column, so let me explain how my experiences with OSU football coincides with the time I spend with men in the Oregon State Penitentiary – the connection today is about motivation, preparation, and – one hopes – redemption.

As I’ve written about before, for the past 6 years, I have taught our incoming freshmen football players in a summer session intended to help them make the transition into college. I teach them a Sociology course in Social Problems, and I always arrange a field trip to one of our state prisons where the young student-athletes can learn about crime, social control, inequality, and family and neighborhood issues from incarcerated men. For the past several years, we have worked with a wonderful inmate club to spend an afternoon talking with incarcerated fathers, and then the football players were able to spend that evening meeting and playing with the kids of those men at a family event in the prison. It’s a wonderful experience for all involved, and in this way, OSU football has a positive connection with state prisons.

The OSU players also know what it is to work hard. Brandin Cooks, in the photo above, played last year as a true freshman, and he is now in his sophomore year. He is currently one of the top college receivers in the country; in this week’s game, he sprained his ankle, got it taped, and came back to finish the game with 8 receptions for 173 yards. Brandin was a standout student and leader in the classroom last summer; it’s clear that his work ethic has translated onto the field. Coach Riley spoke about him in a story in The Oregonian:

Riley talked earlier in the week about Cooks’ motivation when asked how his receiver can go all-out on every play – finishing pass patterns, diving for deflected balls – in practice.

“The best motivation guys can find is self-motivation,” Riley said. “Cooks is a high, high character person. He only knows one way to do it. He works hard. That is catchy for everybody else. Really, we have a whole team like that now – if you don’t do that, then you stand out the other way…”

Back to Cooks’ example. After his father died when he was 6 years old, Andrea Cooks raised four boys by herself – a lesson that stays with Cooks.

“I knew she had hard days, but she kept pushing, and nothing can be harder than that. I’m playing something that I love. She didn’t choose to do that, I’m choosing to do this. If she can get through anything, I’ve got to get through.”

The other impressive example of motivation and preparation that I have been witness to this quarter is taking place within the Oregon State Penitentiary. A parenting program is offered within the prison for men who want to learn parenting strategies and practice those skills. A required component of the program is that the men first have to carry around an egg, and then they graduate to carrying a stuffed animal. The egg/animal represents their child, and they must care for it 24 hours a day for several weeks; they can never leave their “child” unattended. It’s quite a sight to see a small handful of men in a large maximum-security prison carrying around eggs and stuffed animals. It seems a clear sign of maturity and motivation to make that choice.

I got a tiny taste of caring for a stuffed-animal-child in prison last week. Along with 2 college classes and a job with a lot of responsibility, my TA for my Inside-Out class is going through the parenting program. He is also the president of a respected inmate club. He is incredibly busy, but he has an amazing attitude and is a joy to work with. I chose to “babysit” for him during class, and then more visibly babysat for him at his club’s annual banquet, where he was taking care of details and being presidential. It was both funny and somewhat disturbing that some of the elderly guests thought that I had brought my “little friend” into the prison with me; carrying the stuffed animal all night, however, did provide several opportunities to explain the parenting program and the ongoing work and efforts of her “parent,” the club president. It was yet another reason for guests to be impressed by this smart, motivated young man.

Motivation and preparation are paying off for Brandin Cooks and the OSU football team. I can only hope they will also pay off in redemption for the club president and my other hard-working students and friends inside the Oregon State Penitentiary. If and when they get their chance to return to the community, I hope their efforts will be recognized and we – as community members – will offer them the fresh starts they have earned.

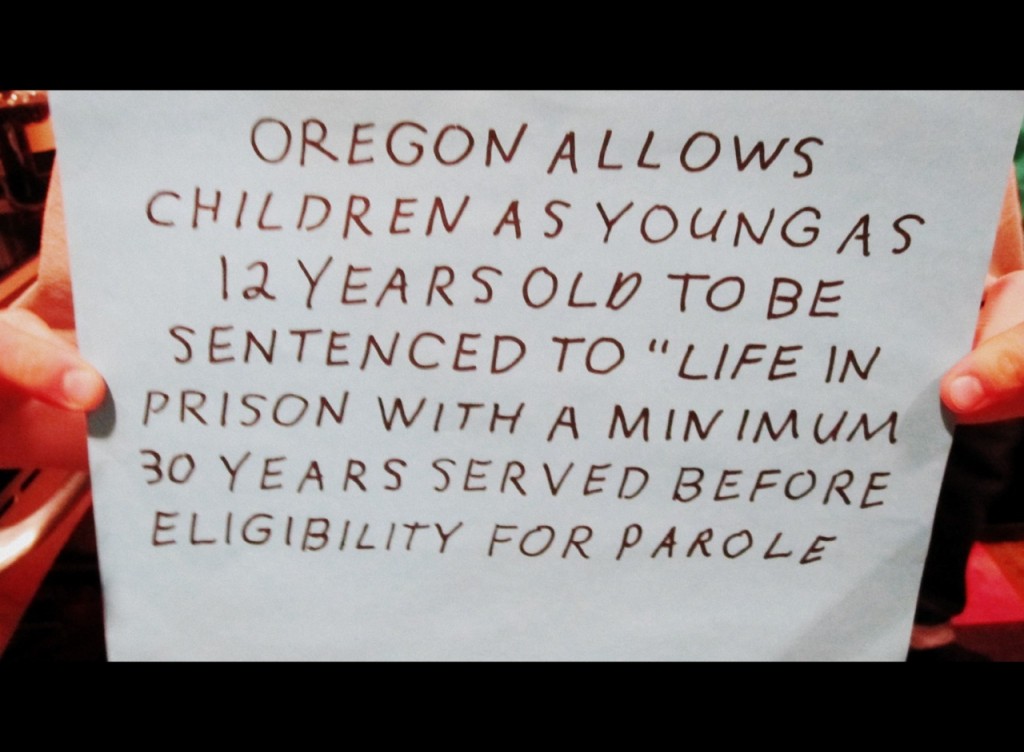

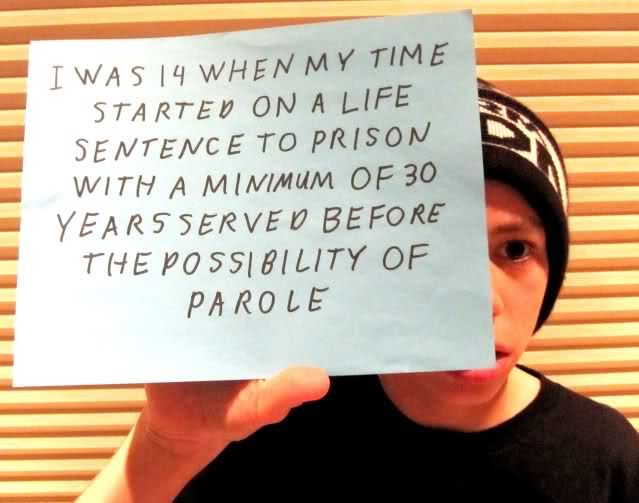

“People are versatile.” I pulled this from what was written in the previous comment. Absolutely, I agree. Beyond that, and in support of that very idea is that “everyone is different,” as no two people or situations are the same. Do I believe that there are some juveniles who once imprisoned should at no point thereafter be released? Yes, I do believe that, however, not based solely on that act which first put them in prison. To say that any choice made as a juvenile discounts one’s ability to grow, learn, change, and become a productive member of society…for the rest of their life! No, not now and not ever. One can change at any stage in life, for better or worse, we as humans are continually going through changes from the moment we are conceived to the moment we pass from life to death, this is simply in our nature. I don’t believe it is just in any way, shape or form to label a juvenile as “scum” that cannot ever change and therefore be sentenced to “Life in Prison” when at that age there remains such an incredible amount of potential for both growth and change. It does no harm to allow someone hope; condemning an individual, especially a juvenile, closes doors we as a society have no right to close. Can anyone know the future? No matter what position of authority is held, I’ll not be convinced that the act of a minor guarantee the outcome of their future based on decisions made as a juvenile.

“People are versatile.” I pulled this from what was written in the previous comment. Absolutely, I agree. Beyond that, and in support of that very idea is that “everyone is different,” as no two people or situations are the same. Do I believe that there are some juveniles who once imprisoned should at no point thereafter be released? Yes, I do believe that, however, not based solely on that act which first put them in prison. To say that any choice made as a juvenile discounts one’s ability to grow, learn, change, and become a productive member of society…for the rest of their life! No, not now and not ever. One can change at any stage in life, for better or worse, we as humans are continually going through changes from the moment we are conceived to the moment we pass from life to death, this is simply in our nature. I don’t believe it is just in any way, shape or form to label a juvenile as “scum” that cannot ever change and therefore be sentenced to “Life in Prison” when at that age there remains such an incredible amount of potential for both growth and change. It does no harm to allow someone hope; condemning an individual, especially a juvenile, closes doors we as a society have no right to close. Can anyone know the future? No matter what position of authority is held, I’ll not be convinced that the act of a minor guarantee the outcome of their future based on decisions made as a juvenile.

The story was accompanied by the even more compelling Reed Saxon/AP photograph at left, showing faceless inmates in uniform lined up along a wall. Regardless of what I might’ve said about the “typical case,” I suspect that readers will call to mind a picture like this when they think of felon voting. Having edited Contexts magazine and the Society Pages, I know how challenging it can be to illustrate such stories. Even if the typical disenfranchised felon is a fortyish white guy who has served his time, how do you tell his story in a way that will visually engage readers? Show a picture of Uggen watering his lawn? Not likely.

The story was accompanied by the even more compelling Reed Saxon/AP photograph at left, showing faceless inmates in uniform lined up along a wall. Regardless of what I might’ve said about the “typical case,” I suspect that readers will call to mind a picture like this when they think of felon voting. Having edited Contexts magazine and the Society Pages, I know how challenging it can be to illustrate such stories. Even if the typical disenfranchised felon is a fortyish white guy who has served his time, how do you tell his story in a way that will visually engage readers? Show a picture of Uggen watering his lawn? Not likely.