One major part of introducing students to sociology is getting to the “this is water” lesson: the idea that our default experiences of social life are often strange and worthy of examining. This can be challenging, because the default is often boring or difficult to grasp, but asking the right questions is a good start (with some potentially hilarious results).

Take this one: what does English sound like to a non-native speaker? For students who grew up speaking it, this is almost like one of those Zen koans that you can’t quite wrap your head around. If you intuitively know what the language means, it is difficult to separate that meaning from the raw sounds.

That’s why I love this video from Italian pop singer Adriano Celentano. The whole thing is gibberish written to imitate how English slang sounds to people who don’t speak it.

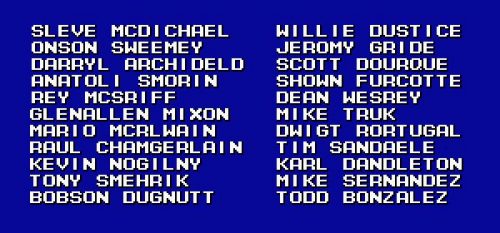

Another example to get class going with a laugh is the 1990s video game Fighting Baseball for the SNES. Released in Japan, the game didn’t have the licensing to use real players’ names, so they used names that sounded close enough. A list of some of the names still bounces around the internet:

The popular idea of the Uncanny Valley in horror and science fiction works really well for languages, too. The funny (and sometimes unsettling) feelings we get when we watch imitations of our default assumptions fall short is a great way to get students thinking about how much work goes into our social world in the first place.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.

Many hope that

Many hope that