Flashback Friday.

In her article “Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack,” Peggy McIntosh talks about a number of types of white privilege, including using the phrases “flesh tone” or “nude” to describe light skin and featuring mostly white people in tv, movies, and advertising.

When I’ve had students read this article, they often argue that it just makes sense to do that, since the majority of people in the U.S. are white. They also question what other color could be used as a “neutral” or “normal” one. In fact, this is exactly what was argued in the comments to this post about the “white” Facebook avatar.

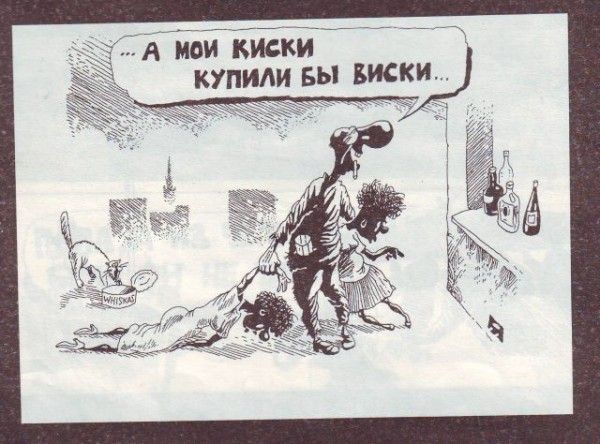

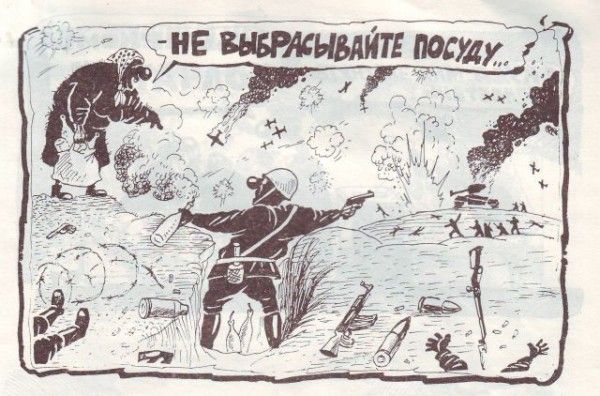

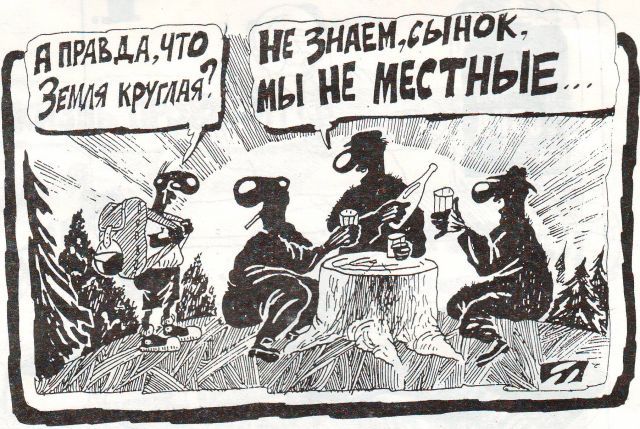

But English Russia points out that in Russia, it’s not uncommon for people in cartoons to be black; not Black racially, but literally black. Below are examples of these cartoons, introduced with English Russia‘s translations.

“My pussy could have Whiskas instead of whiskey.”

“Sir, don’t throw away the empty bottle, I would take it to the recycle point for spare money.”

“Tourist: ‘Is it true that the Earth is round?’ Men: ‘We don’t know son, we’re not locals.'”

Despite the fact that many people in Russia would be classified in the U.S. as white, these cartoons obviously use the color black as a neutral color — the people in the cartoons aren’t Black in any racial sense, it’s just the standard color the artist has used for everyone. You might contrast these with things in the U.S. that are labeled “flesh” or “nude” to counter the idea that there are no other options but a sort of light peach color to be the fallback color when you aren’t specifically representing a racial minority.

Thanks to Miguel at El Forastero for the link! Originally posted in 2009.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.