The day I defended my dissertation I watched Chaotic, the Britney Spears/Kevin Federline reality show, from beginning to end. True story. The next day I pulled all of the paperback classic novels from my bookshelves and donated them to Goodwill. They were mostly tattered Penguin copies of things like The Sun Also Rises and The Stranger. I was done with them.

I was the first person in my family to get a traditional college degree and those books meant a lot to me for a long time. I was an insecure student; a sufferer of the famous imposter syndrome. The books were a signal to myself — and perhaps others, too — that I was a Smart, Educated Person with Intelligent Tastes. They were what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu would call cultural capital, objects that indicate my membership in a particular class. Both Chaotic and the purging of the books were part of the same cathartic expression: relief, incredible relief, at having not-failed. I had a new form of cultural capital now, a more powerful version of that message. I had a PhD. I could afford to toss the paperbacks.

Today, as someone who has officially “made it” in academia, I need those books even less than I did on that transitional day. And, as I’ve made the journey from nervous graduate student to tenured professor, I’ve slowly come to understand what an incredible privilege it is to carry the institutional capital that I do.

Every time I have the opportunity to admit I was wrong or confess a lack of knowledge, for example, I can do so without fear that anyone will think that I’m generally stupid or ignorant. Others assume I’m smart and knowledgeable because of the pedigree, whether I am or not. People who aren’t as lucky as I — who have the wrong accent, the wrong teeth, or the wrong clothes, and who don’t have the right degrees, jobs, and colleagues — they are at risk of being labeled as generally stupid or ignorant whenever they make an intellectual misstep, whether they are or not.

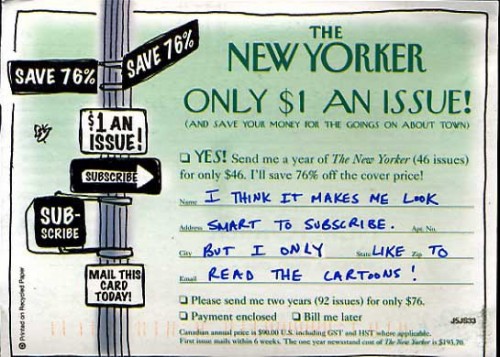

To them, that used Penguin copy of The Stranger may be more valuable than the $0.03 it costs on Amazon. In another part of the social strata, it might be worth it to pay $46 for that subscription to The New Yorker. The subscriber may only read the cartoons, but they don’t mind because, after all, that’s not really what they’re paying for.

Image via PostSecret. Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Image via PostSecret. Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.