Monday is Labor Day in the U.S. Though to many it is a last long weekend for recreation and shopping before the symbolic end of summer, the federal holiday, officially established in 1894, celebrates the contributions of labor.

Here are a few dozen SocImages posts on a range of issues related to workers, from the history of the labor movement, to current workplace conditions, to the impacts of the changing economy on workers’ pay:

The Social Construction of Work

- The surprisingly racist reason we don’t tip flight attendants

- Luxury and the consumption of labor

- The unsung heroes of the crash landing in San Francisco

- Why do firefighters take such risky jobs?

- McDonald’s delusional blame-the-victim budget

- Devaluing hospitality workers

- Domestic behavior as both gendered and raced: Who does what for airlines?

- Child labor and the social construction of childhood

- Child labor, 1908-1912

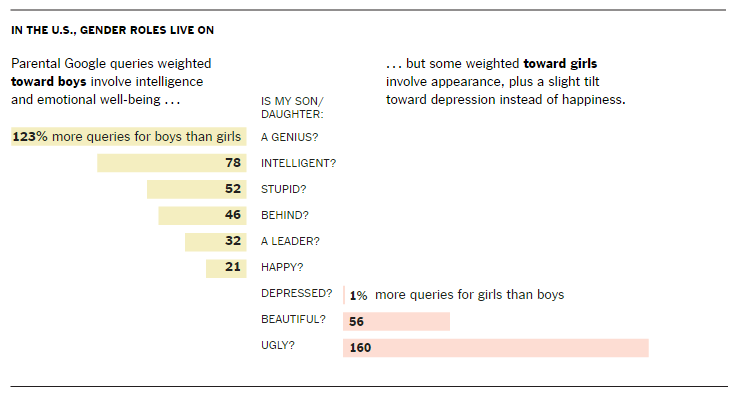

- Women are 49% of the workforce, but we still think work is for men

Work in Popular Culture

- Children’s books and segregation in the workplace

- Alienation and orange juice: The invisibility of labor

- Hurricane Sandy and high fashion: Portraying a class hierarchy

- Whimsical branding obscures Apple’s troubled supply chain

- The “working family” discourse and the invisibility of individuals

- The DJ in American culture: Resonant but misunderstood

- Whiteness and tokenism on the runway

- The solution to patriarchy? Pantene says shine!

- Forbes’ photostock faux paus (what do women workers look like?)

Unemployment, Underemployment, and the “Class War”

- The “Precariat”: The new working class

- When classes collide: Workers and guests at high end hotels

- Who benefits from government programs?

- $22.62/hr: The minimum wage if it had risen like the incomes of the 1%

- Why can’t conservatives see the benefits of affordable child care?

- Food stamps, public policy, and the working poor

- The striking rise in “missing workers”

- Can the minimum wage cover average housing costs?

- Discrimination against the long-term unemployed

- Jon Stewart on class warfare

- Mike Rowe defends blue-collar manual labor

Unions and Unionization

- What have unions ever done for us?

- Footage of strikes and protests

- “Is your washroom breeding Bolsheviks?”

- A way for feminism to overcome its “class problem”

- Target’s anti-union video for new employees

- Unemployment and support for unions

- César Chávez and the fight for farmworkers’ rights

- Hiring non-union workers to staff picket lines

- “A woman’s place is in her union!”

Economic Change, Globalization, and the Great Recession

- U.S jobs are back, but they’re no match for population growth

- The U.S. is replacing good jobs with bad ones

- Whose economic recovery is it?

- Prison labor and taxpayer dollars

- The austerity agenda and public employment

- Comparing black and white job loss in the recession

- The exploitation of worker productivity

- What kinds of jobs are we gaining in the slow recovery?

- Historical look at changes in types of work

- Two American families trapped in a changing economy

- Race and the economic downturn

Work and race, ethnicity, religion, and immigration

- Distrust for Black entrepreneurs

- Race in the NFL draft

- Are Mexicans the most successful immigrant group?

- Race, criminal background, and employment

- The curious evolution of the sign spinnner

- Linguistic occupational segregation

- International politics and the first African American flight attendants

- Luxury and the consumption of labor

- Children’s books and segregation in the workplace

- Whiteness and tokenism on the runway

- Whimsical branding obscures Apple’s troubled supply chain

- When classes collide: Workers and guests at high end hotels

- The surprisingly racist reason we don’t tip flight attendants

- Questioning the benefits of “rescue” from prostitution

- Porn producers with a heart of gold?

- Anti-Muslim bias on the French job market

- Race/ethnicity and the pay gap

- Race, ethnicity, and McDonald’s marketing strategy

Gender and Work

- Majority of “stay-at-home dads” aren’t there to care for family

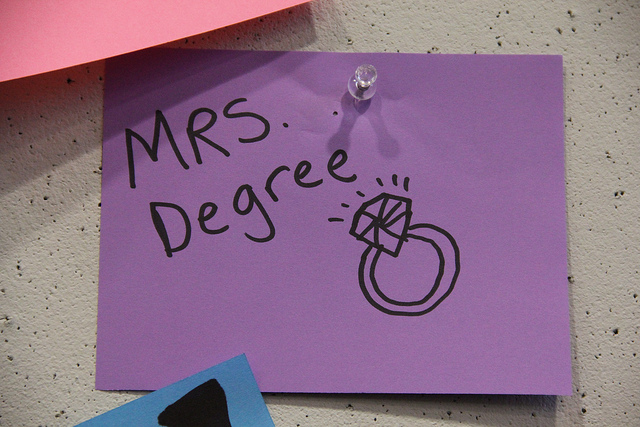

- Most women would rather divorce than be a housewife

- Before the stewardess, the “steward”: When flight attendants were men

- Star Trek is scaring the ladies: Why women don’t major in computer science

- What do little girls really learn from “Career Barbies”?

- “Dude, you need to get into nursing”: How organizations recruit men into nursing

- Stay-at-home mothers on the rise among low-income families

- Gender at The New York Times

- Mother, sex object, worker: The transformation of the female flight attendant

- Female movie stars peak at 34, but men see success till the end (pictured)

- What kind of work does Women’s History month value?

- Men’s and women’s work: It’s the 1950s at Brinks Home Security

- Women’s refusal to be deferent and the words that describe them

- Why “breadwinner moms” don’t portend a coming matriarchy

- Single mother, meet jobless man

- Gender, work, and family time

- First-time mothers and access to paid work leave

- The role of employer selection in gendered job segregation

The U.S. in International Perspective

- Overwork and its costs

- The U.S. is las in paid vacation and holidays

- International comparison of workplace leave policies

- Vacation in international perspective

Academia

- What do professors do all day?

- Gender and the dual career academic couple

- How many PhDs are professors?

- Professors join the “precariat”

- How professors spend their time

- Precious academic moments

Just for Fun

- Who is the highest paid employee of your state?

- Secrets of the Internet Adult Film Database

- Two-thirds of college students think they’re going to change the world

Bonus!

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.