Flashback Friday.

In a great book, The Averaged American, sociologist Sarah Igo uses case studies to tell the intellectual history of statistics, polling, and sampling. The premise is fascinating: Today we’re bombarded with statistics about the U.S. population, but this is a new development. Before the science developed, the concept was elusive and the knowledge was impossible. In other words, before statistics, there was no “average American.”

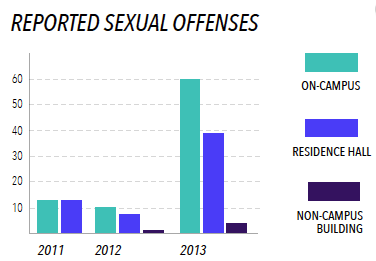

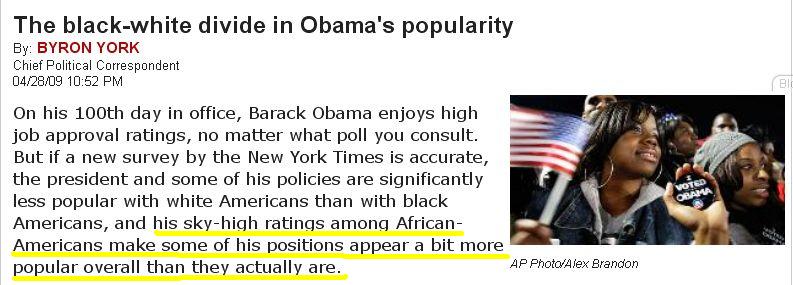

There are lots of fascinating insights in her book, but a post by Byron York brought one in particular to mind. Here’s a screenshot of his opening lines (emphasis added by Jay Livingston):

The implication here is, of course, that Black Americans aren’t “real” Americans and that including them in opinion poll data is literally skewing the results.

Scientists designed the famous Middletown study with exactly this mentality. Trying to determine who the average American was, scientists excluded Black Americans out of hand. Of course, that was in the 1920s and ’30s. How wild to see the same mentality in the 2000s.

Originally posted in 2009.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.