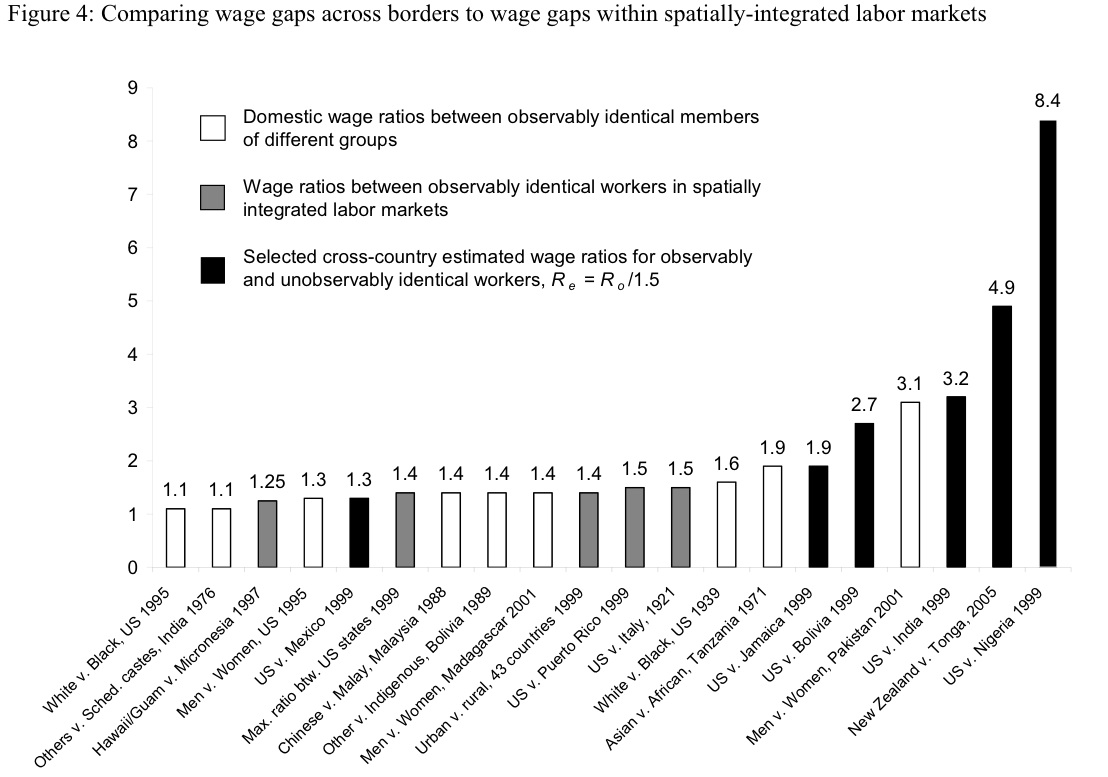

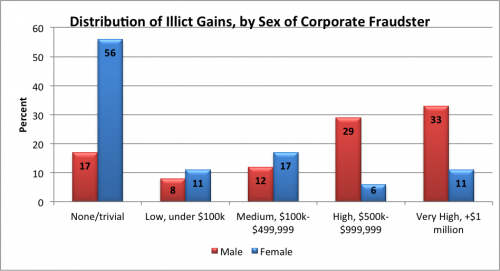

Z from It’s The Thought That Counts sends us this figure showing the wage gap between various types of groups. The point is to show that wage differentials are most extreme across countries, not within them. In an article, Kerry Howley writes:

Wage gaps between observably identical Nigerian workers in the United States and Nigerian workers in Nigeria (same gender, education, work experience, etc) are… considerable. They swamp the wage gaps between men and women in the US. They swamp the gaps between whites and blacks in the US. Actually, they swamp the wage gaps between whites and blacks in the United States in 1855. For several countries, the effect of border restrictions on the wages of workers of equal productivity “is greater than any form of wage discrimination (gender, race, or ethnicity) that has ever been measured.” The labor protectionism that keeps poor workers out of rich countries upholds one of the largest remaining price distortions in any global market.

Click here for the full research report.