The american civil liberties union and talkleft reports on a civil suit that begins today in federal district court. In Johnson v. Wathen, inmate Roderick Johnson seeks damages against texas prison officials, alleging that they ignored his pleas for help and did little to protect him from repeated rape and sexual abuse. According to the ACLU:

Beginning in September 2000, Roderick Johnson was housed at the James A. Allred Unit in Iowa Park, Texas where prison gangs bought and sold him as a sexual slave, raping, abusing, and degrading him nearly every day for 18 months. Johnson filed numerous complaints with prison officials and appeared before the unit’s classification committee seven separate times asking to be transferred to safekeeping, protective custody, or another prison, but each time they refused…Instead of protecting Johnson, the ACLU complaint charges, the committee members taunted him and called him a “dirty tramp,” and one said, “There’s no reason why Black punks can’t fight if they don’t want to fuck.”

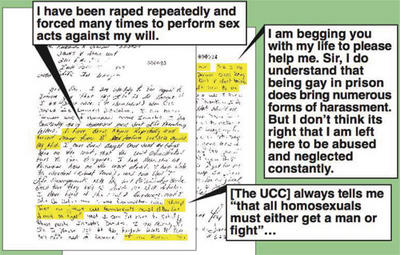

The suit alleges denial of equal protection based on race and sexual orientation and that administrators could have protected Johnson without compromising “legitimate correctional needs.” Although the latter issue might seem paradoxical (how could stopping rape compromise security or legitimate penological objectives?), it is a common defense in prisoners’ rights cases. The ACLU shows numerous pages of Johnson’s handwritten complaints to officials, such as:

The extent of sexual abuse and rape in prisons is often debated by criminologists and reliable data on the subject have historically been hard to find. In the past five years, however, prison rape has received increasing attention and documentation, with a 2005 bureau of Justice statistics study, 2001 and 2003 human rights watch reports, and the prison rape elimination act of 2003. A call for accountability from prison officials seems like a basic step, but complaints from inmates such as Johnson have historically been dismissed as self-serving (the prisoner is “working the system”) or exaggerated (“prison is supposed to be hard”) and still fall on deaf ears in some prison systems. The Johnson complaint cites Farmer v. Brennen, a 1994 case in which the U.S. Supreme Court found that “prison officials violate prisoners’ Eighth Amendment right not to be sexually assaulted when, with conscious disregard of a substantial risk that a prisoner will be raped, they fail to take reasonable measures to abate that risk.”

It isn’t just prison officials, either. People who would never joke about rape outside prisons casually laugh off the idea of prison rape (e.g., when a white-collar offender is sentenced). Either they minimize the harm (as was the case with “marital rape” and “date rape” until recently) or they see inmates as “other” — so dehumanized that they do not suffer the way the rest of us would. The stigma of a criminal record is part of the reason for such “deliberate indifference” on the part of officials and the public, but an inmate’s race, gender, and sexual orientation also appear to play a role in the societal reaction to complaints.