i’ve been doing a lot of interviews lately on crime and unemployment, most recently with mara gottfried and ruben rosario in the pioneer press. my research and reading of the literature suggests that there is a link, but the relationship is generally small in magnitude, crime-specific, and with a tricky lag structure. certainly few people will immediately “turn to crime” when they lose their jobs. nevertheless, a small change in the unemployment rate has big effects for people leaving jail or prison — they are always last in line for jobs, but during recessions there are a whole bunch more people in front of them.

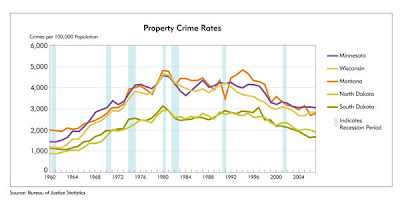

the charts below come from a recent interview with doug clement of the minneapolis fed’s fed gazette. the first one shows property crime rates for the district’s five states during recession and non-recession periods. there appears to be a blip upward during the (blue-shaded) recession months, but one can find recessions during both high-crime and low-crime periods.

after briefly reviewing the economics and crime literature, mr. clement and fed colleagues estimated a county-level fixed effects model of unemployment and crime in the ninth district. though the study was not peer-reviewed and the authors list some standard caveats, their conclusions are generally consistent with the literature:

after briefly reviewing the economics and crime literature, mr. clement and fed colleagues estimated a county-level fixed effects model of unemployment and crime in the ninth district. though the study was not peer-reviewed and the authors list some standard caveats, their conclusions are generally consistent with the literature:

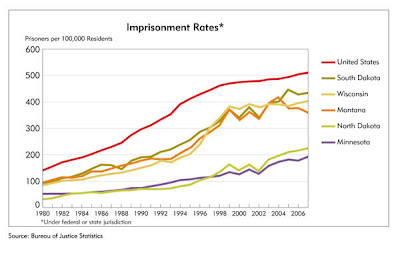

i’ve been struck lately by the divergence between minnesota and wisconsin in incarceration rates, so the chart below caught my eye. while every state in the district is well below u.s. averages, minnesota and north dakota have the lowest incarceration rates in the nation.

even among five “low-incarceration” states, two patterns emerge quite distinctly: minnesota and north dakota track closely, on the one hand, versus montana, wisconsin, and south dakota on the other. i’m curious about the legal, political, and institutional reasons for the differences, but won’t offer any hypotheses until they’re at least half-baked.

even among five “low-incarceration” states, two patterns emerge quite distinctly: minnesota and north dakota track closely, on the one hand, versus montana, wisconsin, and south dakota on the other. i’m curious about the legal, political, and institutional reasons for the differences, but won’t offer any hypotheses until they’re at least half-baked.

Comments