this time of year often brings media requests regarding trends in crime and punishment. answering such calls is important public criminology, but responding can be tricky. reporters often focus on year-to-year changes in rare events such as homicide, but the percent change in such cases can be very misleading. i see my role as providing some context for the local numbers, putting them in historical, national, and international perspective. reporters typically speak with both law enforcement officials and academics, so i try to offer some perspective. i usually focus on 5-, 10-, and 20-year trends and consider the magnitude as well as the direction of change.

by most measures, crime in minneapolis and st. paul rose from 2004 to 2005. this is cause for concern, in part because serious personal crimes such as aggravated assaults and robberies have increased sharply. that said, the base rate of crime in the twin cities is quite low relative to similar-sized cities and relative to local crime rates in the near and distant past. moreover, some of the bad news is a product of legal changes rather than behavioral changes. for example, a new state “strangulation” statute means that many domestic assault cases once considered misdemeanors are now counted among the aggravated assaults in the violent crime index (i learned this speaking with pete crum of the st. paul police department last week). despite the uptick, my take-home message for reporters who want my opinion this year is that national crime rates are at the lowest levels we’ve seen in forty years and that these are good times rather than bad ones.

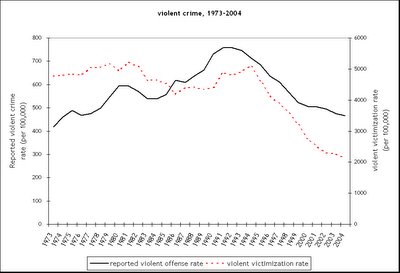

here is my evidence for this assertion. rates of serious violent crime — murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault — continue a long decline, at least through midyear 2005. the chart above shows the national picture for violence as measured by both victimization (red dashed lines – – -) and crimes reported to police (solid lines). i plotted these on separate y-axes so you can see the relative change in each measure. note that violent victimization has been dropping like a stone since the mid-nineties, as have police reports of these four serious offenses.

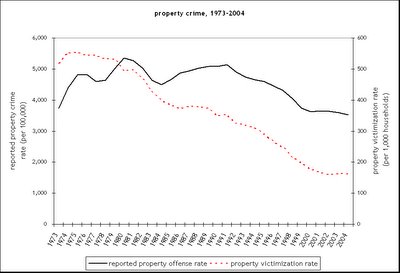

the next figure shows that property crimes of burglary, larceny/theft, and motor vehicle theft also show a decline, although here the rates have flattened since 2002. nevertheless, for both violent and property crimes, victimization levels are at or near record lows, at rates roughly half those of a decade earlier.

of course, none of this makes crime victims or their families feel any better about it, nor does it mean that we no longer need to lock our doors or that we can scale back investments in law enforcement (punishment is another matter). it just means that rates of serious crime are lower today than they were 5 years ago, 10 years ago, 20 years ago, and 30 years ago. good news, right?

Comments