In the wake of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s sad death, many are calling for various “harm reduction” approaches to substance use. Proponents of harm reduction have identified lots of ways to reduce the social and personal costs of drugs, but they often require us to shift our focus from the prevention of drug use itself to the prevention of harm. Resistance to such approaches often hinges on the notion that they somehow tolerate, facilitate, or even subsidize risky behavior.

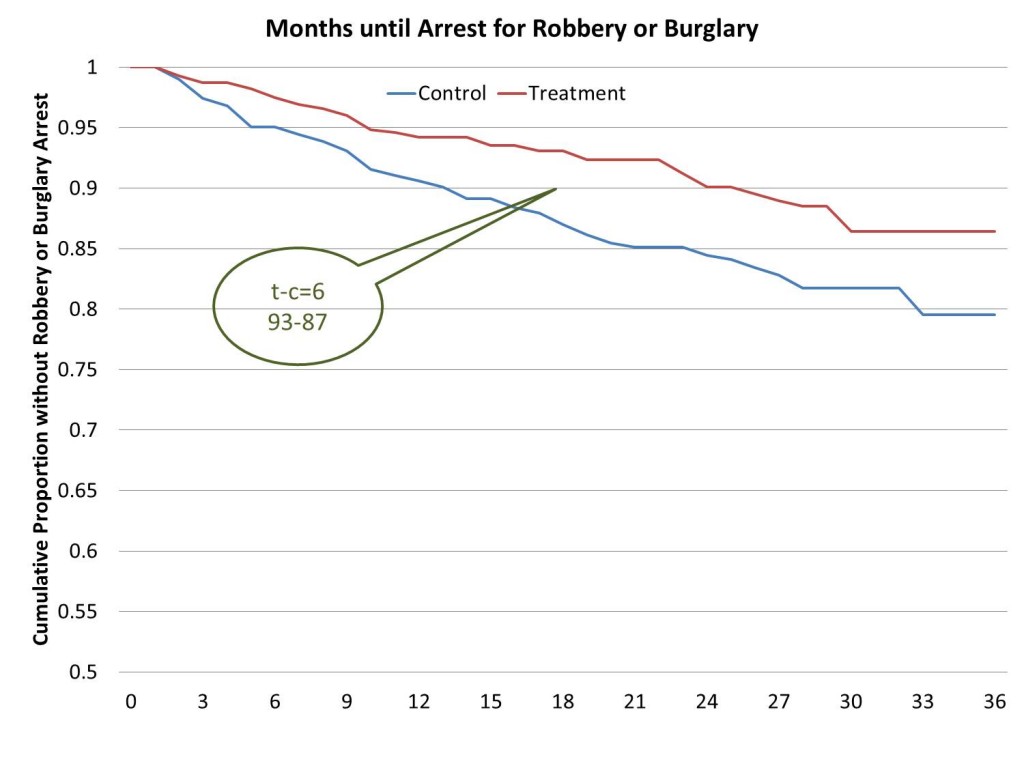

This tension emerged clearly in my new article with Sarah Shannon in Social Problems. We re-analyzed an experimental jobs program that randomly assigned a basic low-wage work opportunity to long-term unemployed people as they left drug treatment. In some ways, the program worked beautifully. The job treatment group had significantly less crime and recidivism, especially for predatory economic crimes like robberies and burglaries. After 18 months, about 13 percent of the control group had been arrested for a new robbery or burglary, relative to only 7 percent of the treatment group. Put differently, 87 percent of those not offered the jobs survived a year and a half without such an arrest, relative to 93 percent of the treatment group who were offered jobs.

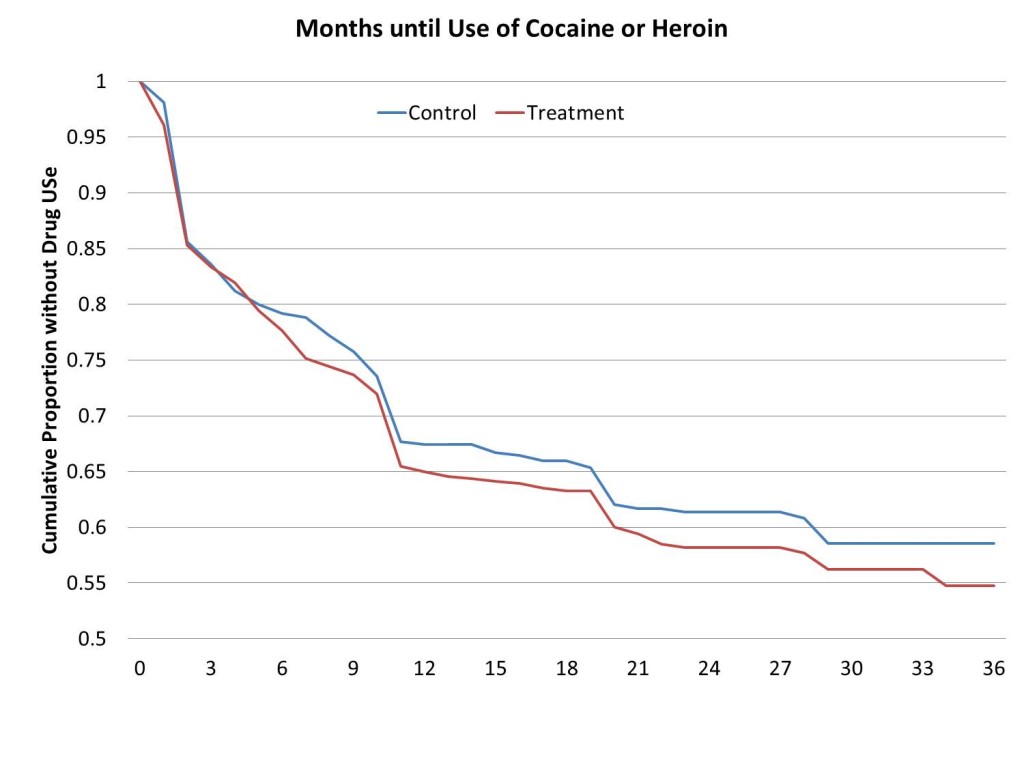

A randomized experiment that shows a 46 percent reduction in serious crime is a pretty big deal to criminologists, but the program has still been considered a failure. In part, this is because the “treatment” group who got the jobs relapsed to cocaine and heroin use at about the same rate as the control group. After 18 months, about 66 percent of the control group had not yet relapsed, relative to about 63 percent in the treatment group. So, there’s no evidence the program helped people avoid cocaine and heroin.

From an abstinence-only perspective, such programs look like failures. Nevertheless, even a crummy job and a few dollars clearly helped people avoid recidivism and improved the public safety of their communities. So, did the program work? From a harm reduction perspective, a jobs program for drug users surely “works” if it reduces crime and other harms, even if it doesn’t dent rates of cocaine or heroin use.

Productive Addicts and Harm Reduction: How Work Reduces Crime – But Not Drug Use

Christopher Uggen and Sarah K. S. Shannon

Social Problems

Vol. 61, No. 1 (February 2014) (pp. 105-130)From the Works Progress Administration of the New Deal to the Job Corps of the Great Society era, employment programs have been advanced to fight poverty and social disorder. In today’s context of stubborn unemployment and neoliberal policy change, supported work programs are once more on the policy agenda. This article asks whether work reduces crime and drug use among heavy substance users. And, if so, whether it is the income from the job that makes a difference, or something else. Using the nation’s largest randomized job experiment, we first estimate the treatment effects of a basic work opportunity and then partition these effects into their economic and extra-economic components, using a logit decomposition technique generalized to event history analysis. We then interview young adults leaving drug treatment to learn whether and how they combine work with active substance use, elaborating the experiment’s implications. Although supported employment fails to reduce cocaine or heroin use, we find clear experimental evidence that a basic work opportunity reduces predatory economic crime, consistent with classic criminological theory and contemporary models of harm reduction. The rate of robbery and burglary arrests fell by approximately 46 percent for the work treatment group relative to the control group, with income accounting for a significant share of the effect.