A new Bureau of Justice Statistics Report by Erica Smith and Jessica Truman shows a significant decline in the Prevalence Of Violent Crime Among Households With Children, 1993-2010. The study is based on the large-scale annual National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) and it differs from standard victimization reports in its explicit focus on households with kids.

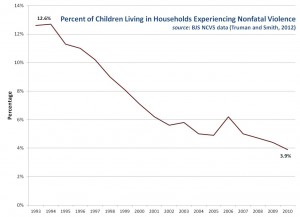

The chart below shows the percentage of households with children in which at least one member age 12 or older experienced nonfatal violent victimization (rape, sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, and simple assault) in the previous year. This does not necessarily mean that the children witnessed the violence or that they were even aware of it, but it does give us a pretty good sense of whether kids are living with household members who are themselves experiencing violence. And the NCVS provides the sort of high-quality nationally representative survey data that are useful in charting big-picture trends. According to the report, this rate dropped from 12.6 percent of children to 3.9 percent in the past 18 years (the blip in 2006 is due to a shift in methodology). That’s an impressive 69 percent decline since 1993.

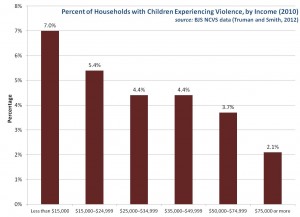

These numbers still seem high to me, but I think it is because simple assault (which encompasses a pretty broad range of behavior) accounts for the bulk of the violence (about 2.6 percent of the 3.9 percent total in 2010). Which kids are most affected? Children in urban areas, children of color, and lower-income children are most likely to live in households experiencing violent victimization. Rates are significantly higher for urban households with children (4.5 percent) than for rural (3.6 percent) or suburban (3.2 percent) households. With respect to race and ethnicity, rates are lower fir households headed by Asians/Pacific Islanders (1.4 percent) than for households headed by multiracial persons (5.6 percent), American Indians/Alaskan Natives (5.3 percent), African Americans (4.9 percent), Hispanics (4.0 percent), and Whites (3.4 percent) (the authors caution, however, that estimates for several of these groups are based on a small number of cases). There is also a very clear socioeconomic gradient to violent victimization: the greater the household income, the lower the rate of violent victimization, as shown below.

This sort of story might be familiar to criminologists: the overall crime situation is improving, but victimization is heavily concentrated among the most disadvantaged. Nevertheless, this report is important and useful in showing how children’s proximity to violence is changing in some ways — and not changing in others.

Comments